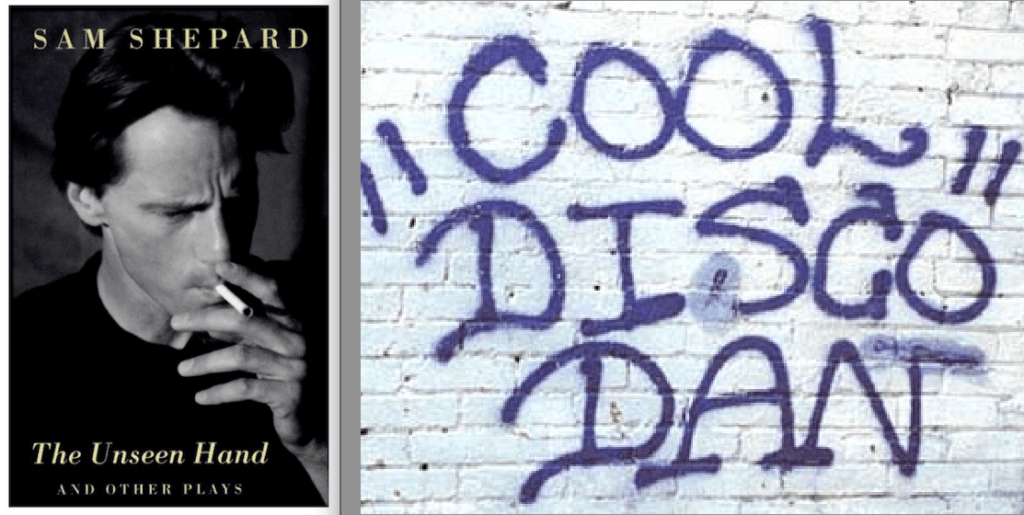

Sam Shepard, Cool ‘Disco’ Dan: Unique American Identifiers

By • July 31, 2017 0 473

Sam Shepard, writer, playwright, actor, teacher, sort of cowboy and farmer, movie star, New Yorker, avant gardist, has died.

Last week, so did Cool “Disco” Dan, aka Danny Hogg, a Washington graffiti artist and legend.

Too soon. Shepard was 73, Hogg was 47.

There’s a fragile, blowing-in-the-wind strand of rope that connects these two—they were American types and originals, not because of race or color, not as artists in terms of stature or genre, but as American identifiers.

Shepard probably wrote thousands of words, some of them transformed into gritty, unheard-of kind of plays that cut to the bleeding, screaming never-quite-seen-before places and hearts of the west.

Cool “Disco” Dan wrote three words, over and over again in bright, big blue, red, yellow jagged letters all over Washington when Washington was something else—post riots, primo Barry, part of still a wreck. He was “a Washington street artist,” which means you saw his name everywhere, in alley garages in the city’s different neighborhoods, from the vantage point of a Metro car on the Red Line.

Cool “Disco” Dan — and quite a few others — out of defiance, giving new meaning to make a name of yourself or make yourself out of a name, created an art scene of sorts. What he did—while well remembered and colorful and impressive—did not endear himself to the owners of the garages or businesses where his name glowed in the dark. It was also illegal. And legendary.

Of course, when you’re doing this, everybody knows your name, but nobody should really knows who you are. That wasn’t the case with Cool “Disco” Dan. They made a movie about Hogg, who was a Capitol Heights resident of the city during hard times and with a troubled life. “The Legend of Cool ‘Disco’ Dan” was also about the D.C. street art scene in general.

Cool “Disco” Dan was all about urban American life, and a particular urban scene, where it seemed it was always hot in the summer, where buildings were going down and up, up and down and neighborhoods were gritty and teeming — although if you’ve been around European cities in the last few years, graffiti, especially along river routes, is abundant.

Shepard was a lot of things—but grit was paramount in some ways. He, too, had a tense upbringing, raised by a father, a World War II bomber pilot in the Pacific, who was “violent and alcoholic,” he acknowledged.

Family was the big subject for Shepard’s short and slightly bigger plays—the “implosion of family.” But the plays, intense, abstract, funny, landing punches, were something new, as well as craggy, seeming to burst out of the tough, overheated, endless landscapes of the American West.

Think about this: one of Shepard’s early plays, after he had landed in New York smack dab in the middle of the thick days of the avant garde in the city, was called “Cowboy Mouth,” written with his lover Patti Smith, and was staged in April 1971, which made Patti Smith Patti Smith.

Right after that, he joined Bob Dylan on his Rolling Thunder review of 1974 as a screenwriter for Dylan’s weird “Renaldo and Clara.”

Then, after a series of acclaimed one-act plays came his family trilogy plays and others, which put him in the ranks of top American playwrights. It’s an impressive list: “Buried Child,” “True West,” “Fool For Love,” “A Lie of the Mind” and “Curse of the Starving Class.”

Now we come to Sam Shepard, movie star. Look at that face: craggy, but also handsome, eyes staring back, knowing stuff, challenging. You think you could get a paper cut from that face if you touched it.

He was good at it, coming naturally or otherwise, although he was reluctant to perform on stage. But the camera loved him, or maybe just gave in to him, like in a holdup. Shepard won an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of pilot Chuck Yeager in “The Right Stuff.” He did a film version of “Fool for Love” with Kim Basinger, directed by Robert Altman. He starred as the grim commanding officer in “Black Hawk Down” and was featured in many other films.

Shepard could be menacing, but in truth he looked truthful—discomfited and not without a conscience, like a strong wind out of the West.

He was in a movie called “Frances,” where he costarred with the rising star Jessica Lange, with whom he had a relationship for 30 years, fathered two children — Lange, a woman who despite having oodles of glamour and sex appeal, was and fundamentally became a great character actress.

We saw them together at a Kennedy Center premiere of “Sweet Dreams,” the Patsy Cline biopic from 1985 in which he starred. Amid all the media, press and TV cameras, he was sturdy, protective and strong.

We also saw a production of “Fool For Love,” staged by Bart Whiteman’s Source Theater in the 1980s. We watched the warring couple battle in an alley under almost natural night.

Can’t say for sure, but I wouldn’t be surprised if one of Cool “Disco” Dan’s signatures wasn’t on the garage door.