In the summer of 1978, I attended an alley party, a gathering of neighborhood friends on Capitol Hill near the Eastern Market Metro Station. Toward mid-afternoon, there was a buzz of energy in the crowd and you could see a thirty-forty-something black man in a summer suit making his way through the people, shaking hands, announcing himself. “Who’s that guy?,” I asked a friend. He came our way and stretched out his hand. “Hello,” he said. “I’m Marion Barry, and I’m running for mayor of Washington.” He looked me straight in the eye, no blinking, straight up.

Back then, not even Barry—who is neither humble, modest nor shy about his achievements and talents—had any idea of just how far he would go, how much of an impact he would have on his adoptive city, for better or worse, just how far he might rise and how low he might fall, or how much he would seep into the lasting imagination of the city’s residents, black and white.

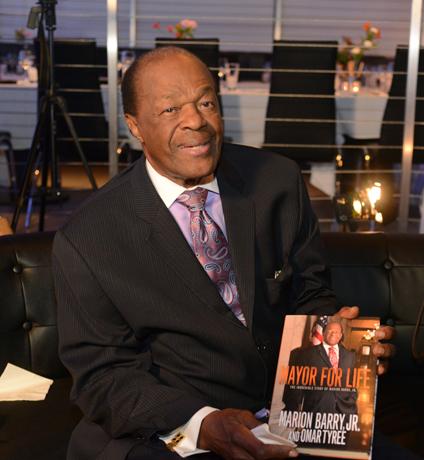

Some 36 years later, here we were again. He walked into the Four Seasons Hotel in Georgetown, and at first glance—walking carefully, but straight up, splendid gray suit and tie—he still had some of that charisma that makes you pay attention. But he was also, at age 78, a little diminished—by health issues and by time.

But we were all here together because of the book.

There is no end to the story of Marion Barry, or as the title of his book goes “Mayor for Life, The Incredible Story of Marion Barry Jr.”

The book—long anticipated and long put off—is what it’s all about now in Barry’s life: interviews, an appearance at the National Press Club, an unusual sit-down, “on-the-record” dinner with journalists at the Look Supper Club on K Street, a forum cum-love fest sponsored by the Washington Informer at the Congress Heights school on Martin Luther King Avenue in Ward 8, all part of a here-there-and-everywhere mini-book tour. The book getting its share of knocks from the media, and others, but also praise from fans. Wherever Barry goes, his story goes with him.

If you’ve lived in the Barry age, you get instant flashbacks encountering him. You remember the flamboyant first-time mayoral candidate, the politician in the dashiki, the job-maker for the city’s struggling African-American population, presiding over a construction boom, charming some but not all CAG members at their meetings; the infamous crack-smoking Vista Hotel tapes, the trial, coming back from a six-month prison sentence, getting re-elected to a fourth mayoral term, getting elected to the Ward 8 council seat, where he remains to this day, still drawing attention, still getting into trouble, still a force.

The book tour is bringing out almost every Barry incarnation we’ve seen—as well as the familiar tropes in reaction to the book by his critics. Modesty is never an issue. At the book dinner he said, “Courage, tenacity and vision, that’s Marion Barry in a nutshell.”

Face to face over lunch, he’s a little quieter, although no less full of certainty. “I don’t want my life to be just about the Vista thing, it was a life of accomplishment, where I helped people get a fair share of what they’ve been denied, in terms of jobs, in terms of work, in terms of participating in the business of this city. When I came here in 1965, this was still a sleepy Southern town. It was segregated, and black people weren’t a part of the economy the way they should have been, and when I was elected mayor I changed all that.” Asked if he had any regrets, he almost scowls. “Sure, of course, I’ve got regrets, who doesn’t,” he says. “When it comes to that, I sure wouldn’t have gone up to that hotel room if I had to do it over.”

The book is a kind of freight train, going full speed around the curves, dropping cargo and information, with some empty cars on it. If you want Vista, it’s there in detail, according to Barry, if not according to other accounts and observers, often graphically.

But the book, written with novelist Omar Tyree, does touch on his early years, where you get a better sense of what may have formed Barry. He was born in Itta Bena, Mississippi. “I grew up poor,” he will tell you. His father was a sharecropper who died when Barry was four. “I didn’t have a role model,” he said.

He grew up in Mississippi, in Arkansas, in Tennessee, during his formative years. Those were also the years of real segregation and Jim Crow in the south, where blacks and whites drank at different water fountains were. “I tried it once, I wanted to see what it was like to drink water from the white fountain,” he says. “You just didn’t do that.”

In the end, Marion Barry became his own role model. Barry pursued science, has a master’s degree in Chemistry and became an organizer and leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during some of the most dramatic years of the civil rights movement.

“My mother [Mattie Cummings] picked cotton, but she later became a domestic. She insisted to the people who she worked for that she would come in the front door, not the back door. She said to them “If I’m good enough to teach and raise your kids then I’m good enough to come through the front door. And she did.”

His vision about himself is heroic, in terms of the difference he made in the city for its black residents. “I knew what needed to be done and I did it,” he says. From the moment he came to town as a SNCC organizer with the reputation of a go-getter and firebrand, he kept moving forward. “People liked me, people followed me. I ran for the school board and won, I ran for the city council and won, I ran for mayor and won.”

“You want to know why I came back after all that, I was on the council again, but I went to Safeway on Naylor Road, to get some groceries, and I couldn’t get out of there for two hours. It’s true.” People said, “why don’t you run again, Marion? The city, the people need you. So I ran,” he says. That was his last mayoral run, in 1994, when he beat both Council member John Ray and Mayoral incumbent Sharon Pratt Kelly, who ran a distant third. That was also, after his victory, when he told disgruntled white voters “to get over it.”

The segregated South framed Barry’s political context. In the book and in conversation, he often refers to white folks and the white establishment as a kind of political antagonist, against himself and African-Americans in general.

He is asked about Mayor Vincent Gray’s campaign platform of “One City,” of bringing the city together racially and ethnically. “It’s not real,” he says. “Can’t be done. It’s just not real. It’s a slogan, that’s all, a pipe dream.” Barry endorsed Gray in the Democratic primary earlier this year, in which Gray, operating under a cloud, was beaten by Ward 4 Council member Muriel Bowser. Barry said he’ll be supporting Bowser.

Talking about the new demographics of the city and its neighborhoods in which the black population is declining, he says it’s “gentrification, pure and simple, that’s driving people out of the city, the people who made up the backbone of this city. It’s a disgrace. ”

“I’m not done,” he said. “I’m going to continue fight for economic empowerment. If you don’t have capital, you don’t have power.”

- Jordan Wright

- Jordan Wright