‘Elaine de Kooning: Portraits’

By • May 11, 2015 0 1409

In the decade following World War II, a 40-year-old Dutch immigrant named Willem de Kooning dominated New York City’s art scene. With a few fellow painters, he guided the evolution of Abstract Expressionism and defined an era of American art that would change the postwar world.

At this height of power and influence, de Kooning was – for fellow artists if not for the press, who favored in personality the cowboy brass of Jackson Pollock and the fierce erudition of Mark Rothko – a vortex, whose talent, sensibilities and ideas pulled almost any aspiring painter into its overwhelming influence.

This was when he married Elaine, an aspiring young painter who would become his first wife and, ultimately (despite periods of long separation), his lasting life partner.

While Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989) would have been the first to concede the great influence her husband had on her artistic development, she took her long and illustrious career down a road that almost no other painter successfully traveled, merging Abstract Expressionist aesthetics with portraiture.

Elaine de Kooning managed to navigate and manipulate the roiling tides of Abstract Expressionism, whose muddy, streaked and pock-marked canvases defied taming, to achieve nuanced faces and expressions, delicate gestures, postures and anatomy, without surrendering the style’s spontaneous energy and unpredictability.

At the National Portrait Gallery through January 2016, “Elaine de Kooning: Portraits,” takes us on a retrospective journey through de Kooning’s evolution as a portrait artist, covering the 1940s through the 1980s. A beautiful and refreshing exhibition, it shows that de Kooning is far too bright a talent to linger any longer in the shadow of her husband’s legacy.

The paintings from the 1950s, amidst the pull of her husband’s influence, have a sort of whirlpool effect: all lines and shapes are pulled as if by a black hole toward the center of the canvas – this epicenter sometimes being a pair of crossed hands, sometimes even just the button of a jacket.

Faces are often less defined, sometimes smudged out entirely. On the whole, these effects, while attractive (in fact, among my favorite in the exhibit), almost suggest that de Kooning was still struggling to reconcile an unwieldy abstract approach to fit the representational constraints of portraiture.

Her 1952 portrait of her husband is a good example of this, his entire face reduced to an aquiline nose and a tuft of hair on a muddy pink ring of paint – though it still manages to reveal the man clearly in caricature if you know what he looked like.

The second gallery devotes a great deal of space to de Kooning’s series of portraits of President John F Kennedy. While significant, these were ultimately library commissions and they feel a bit like that. The most interesting thing de Kooning achieves in these paintings is subconscious. She captures JFK, but the airy, almost hazy atmosphere surrounding him makes them portrayals of what it feels like to be in his presence: awe, reverence, reservation, timidity, even attraction.

In the galleries that cover the remainder of her life, we find hints of Matisse, Velázquez and Picasso, John Singer Sergeant, even Roman frescos and religious altarpieces, all intermingling in a subtle but profound painterly sophistication.

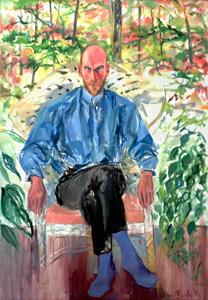

Her portrait of Aladar Marberger, from 1986, attributes the sitter with the ferocity and certitude of Pope Innocent X, but in an airy, Bonnard-like garden landscape. Marberger sits in a wicker chair on a pink cushion, purple socks covering his feet. Trellised vines and palm plants surround him, and the background dissolves into a pink and green tangle of thin branches and narrow tree trunks. This lovely and provocative interplay between severity and lightness of tone could easily collapse in on itself and fail utterly. But de Kooning turns it into something worth treasuring.

- Elaine de Kooning, “Aladar Marberger #3″ (1986). Collection of Donna Lynne Marberger & Dr. Jon L. Marberger.