‘Seeing Nature’ at the Phillips

By • April 6, 2016 0 883

For a long time I’ve harbored a shameful secret: I adore landscape paintings.

As revelations go, that was probably an underwhelming spectacle, but the cultural climate around art today is a strange affair. As prevalent as the landscape is through art history, it feels as if the subject has been slowly relegated to the overstock aisles.

This is not to say that landscapes get no attention. Should a museum be so blessed to own a Monet, a Cezanne, a Turner or anything of the ilk, those are sure to be among their prized holdings, installed indefinitely. But for every theme-driven exhibition I’ve seen focusing on portraiture, abstraction or the still life, I cannot think of a single one in recent memory that dealt directly with the art of landscape.

In fact, “Seeing Nature: Landscape Masterworks from the Paul G. Allen Family Collection,” at the Phillips Collection through May 8, might be this city’s first major exhibition devoted to landscape painting in the six years I’ve covered arts for this paper. (If my memory is failing, I blame my editor entirely.)

Why is this?

It is impossible to really know, but as a thought experiment I might say it’s because there is relatively less historical or cultural marrow to sap from a landscape than from any other subject. A cypress tree in 19th-century France is more or less the same sight now as it was then. An artist can handle the subject differently, but a tree is always a tree.

By contrast, the content of a portrait or still life is hardwired with information relevant to cultural shifts and social evolution — fashion and hairstyles, furniture and man-made objects — which offer distinctions as to what, when and sometimes who we are seeing. And abstraction by its very nature is the deconstruction of a given cultural mood. Any Abstract Expressionist exhibition may as well be a show about American postwar bravura and the riveting detonation of artistic preconceptions.

By this interpretation, landscapes offer comparatively less opportunity for a museum to present new and interesting content. And so they simply break up these lovely works by period, assign them to the appropriate galleries (see the Impressionist galleries at the National Gallery of Art) and leave them to be passingly admired by their audience on their way to the major loan exhibitions.

What “Seeing Nature” demonstrates (or perhaps simply reminds us of) is the billowing richness of landscape painting through history. While it does not always provide the same cultural clues as other subjects, it is probably the ultimate vessel through which history’s greatest artists have experimented with paint and honed the very matter of their medium.

The other remarkable aspect of this show is that the works all come from one collector, Paul Allen, cofounder of Microsoft and an evidently wicked connoisseur with a sharp eye for paintings.

The works are all pretty much jaw-dropping, obscure masterpieces by some of the greatest artists in history, as well as works by a scrupulous selection of secondary artists who, for my dollar, have always deserved to be among this pantheon. To see Maxfield Parrish, Thomas Hart Benton and Arthur Wesley Dow taking their place with Edward Hopper and Georgia O’Keeffe feels like a small but momentous vindication. Similarly, to exhibit Milton Avery, a hugely important American artist who was all but left out of the major art historical literature, as a contemporary of Max Ernst evinces a deep understanding of 20th-century art, well beyond the history playbooks.

All this still omits a broad swath of works in the show that offer new insights into many of our most beloved painters. Gustav Klimt’s “Birch Forest (Birkenwald)” shows a different side to the artist’s process that is worlds apart from the hyper-stylized human jewelry of his portraits of Austrian high society. Aggressively naturalistic, “Birch Forest” shows a compulsive, almost scientific observer at work; the tree’s bark and the crunchy forest floor are rendered to a fault.

Monet’s “The Fisherman’s House, Overcast Weather” is stunning even by Monet’s standards. Its panoply of colors and flickering brushstrokes serve to create an inversely subdued and intimate portrait of brittle, windswept brush and a raw gray sky. It is the kind of painting you want to wake up to (if, like me, you’re slightly fond of your own melancholy).

A suite of five paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicts “The Five Senses.” What a richness of sensory allusion, an ode to that which makes up our experience with the world and the functions we employ to perceive it.

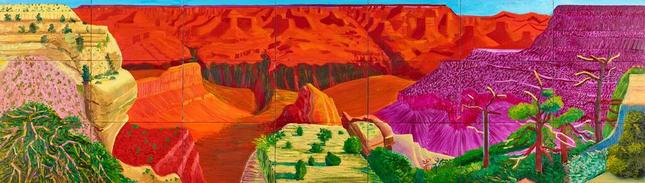

The final gallery is reserved for contemporary works, which actually do give us a glimpse of the future of landscapes. Ed Ruscha’s untitled painting is like a post-apocalyptic interpretation of Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” all blackness and hard angles, and the radioactive hot-pink glow of David Hockney’s “The Grand Canyon” manages to give a strangely similar feeling.

The show ends on two paintings by Gerhard Richter, “Apple Tree” and “Vesuvius,” which offer a meditation on the nature of observation today as much as any denouncement of the modern landscape. (I’ll leave it to you to make the none-too-subtle connections between the paintings’ titles and his prognosis of our human fate.) Concisely rendered paintings of analog photographs of their subjects, they begin to border on abstraction when you consider their odd extrication from the natural environments they depict. The paintings are at once an affirmation of art’s power and a warning not to trust that the world is so flattering or beautiful as it is romanticized through art.

Nevertheless, once you experience “Seeing Nature,” the world certainly becomes a far more beautiful place.

- “The Grand Canyon,” 1998. David Hockney. | Courtesy The Phillips Collection.