‘Luminous Landscapes’ at the National Building Museum

By • April 20, 2016 0 1408

There is a stirring tranquility in the architectural landscape photography of Alan Ward that causes me great human envy. As his work shepherds the viewer through the great parks, gardens, graveyards and winding mountain roadways of America, the photographs become living documents which evince that unalienable right so judiciously promised by Mr. Jefferson so long ago: the pursuit of happiness.

Ward’s photographs exhibit an encompassing soundness embedded in the foundation of our very earth. It is an emotional sensation disparate from the roiling charade of political demarcation and career spectacle that governs our daily lives, and it drives me nearly mad to know that someone out there has not only traversed this divine presence for a living but also captured it.

At the National Building Museum through Sept. 5, “Luminous Landscapes: Photographs by Alan Ward” is a sublime escape into the backyard of America, where you can unlace your shoes or roll down the window of your car, let the thick air wash over your face and know that the feeling is real.

“Successful works of landscape architecture have a certain resonance with us,” Ward said in a recent conversation with The Georgetowner. “After all, we are connected to land, humans always have been. And exceptional landscape designs express our relationship with the land. So when you see these images you see that it’s possible to design and build in harmony with the land.”

To that end (and among other things), “Luminous Landscapes” is a road trip. The exhibition journeys from the grassy tidewaters of the Deep South, over the rolling hills of the Piedmont and New England’s groves of academe, across Appalachia and into the sun-flecked nape of the Midwest, all the way up to the mossy shadows and old growth majesty of the Pacific Northwest.

Taken throughout Ward’s 40-year career, these photographs become a sort of domestic passport, documenting the expansion and evolution of our country. Through his lens, we get to see and understand the impact of the most significant designs in American landscape architecture; each site is either itself a landmark or emblematic of a pivotal transition point in landscape design.

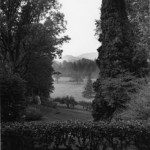

At Middleton Place in Charleston, South Carolina, one of the oldest surviving designed landscapes in America (dating to the 1740s), earthen terraces descend in long steps from the main house to the river. The plantation owner, Henry Middleton, relied on European precedents to achieve the vantage needed to oversee farming in the pre-Civil War era.

(All that aside, Ward’s photograph of a venerable, hulking oak tree at Middleton Place — framing the distant landscape with its branches as it cranes almost horizontally over a flooded rice field — is one of the most satisfying compositions one could ever hope to see.)

About 140 years later in Bratenahl, Ohio, the architect Charles Platt put a popularized Italianate influence to work on Gwinn, a distinctly American estate on the shores of Lake Erie that masterfully integrated ornate architecture in a billowing landscape. A spacious pergola is built into the hillside; the formal garden flanks the entry drive like an extension of the rooms in the house. Through Ward’s lens, the stonework seems to grow out of the surrounding environment, all the way down to the slick steps that break the seawall and invite us into the water.

By the 1970s, the Bloedel Reserve in the state of Washington pared away the ornamentation of previous generations of landscape architecture and explored architecture’s relationship to ecology through a design involving the forest, meadows and water. Here, the way that Ward portrays the walking paths, hedgerows and stonework that move in and out of natural streams, one can barely discern what is naturally occurring and what was manufactured.

What is so lovely and engaging about the way that Ward photographs these natural subjects is that he offers viewers the experience of standing on these very grounds, as if moving naturally through the landscape.

By way of comparison, Ansel Adams famously elevated his camera beyond the foreground, achieving a heroic, mythical quality in his sweeping landscape photography. Ward does almost the opposite, connecting the environment to the human scale and putting the viewer within the landscape.

“Ansel Adams was trying to transcend the human experience,” he said. “What I am trying to do is create an experience of a place, to draw you through it. These places were designed to walk through, for instance, so many of my photos are on paths.

“After Adams, and even at the same time, there started to be more of a critique of the landscape and the built landscape,” Ward continued. “So much landscape photography is highly critical, showing us how we’ve despoiled the earth and how development has overtaken natural landscapes. But I am trying to show that we can build wisely and in harmony with the natural landscape, and I want to find places where land and culture have come together to forge these beautiful, inspiring places.”

With these works, Ward has developed a resounding and poetic argument, and contributed significantly to the dialogue about modern society’s relationship with the natural world.

Who knew that it was possible to bottle transcendence?

- “Live Oak and Flooded Rice Field, Middleton Place.” | Courtesy National Building Museum.