A Refrain of Triumph Over Adversity: ‘The Migration Series’

By • December 21, 2016 0 1522

In 1940, a 23-year-old artist named Jacob Lawrence set to work on a 60-panel series portraying the movement between the world wars of more than a million African Americans from the rural South to the industrial centers of the North. This mass exodus, the largest population shift of African Americans since the time of slavery, was a search for a better life, an escape from wartime shortages and oppressive conditions for blacks in the South.

Almost instantly, the series became an icon of American art, snatched up in record time in a split acquisition by the Phillips Collection and the Museum of Modern Art in 1942, just a year after its completion. The Phillips is currently displaying the complete series, reuniting the odd-numbered panels it owns with MoMA’s even-numbered panels. “People on the Move: Beauty and Struggle in Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series,” on view through Jan. 8, explores the various manifestations of migration underlying Lawrence’s powerful visual narrative.

The conversations the series raises surrounding our current political climate are hard to ignore. Obviously, the team that put this exhibition together began their work long before the election unfolded, and it is not the job of scholars and historians to act as political commentators. However, they were probably aware of the timing.

So let’s not assume that the choice to exhibit a seminal collection of American artistic masterworks focused on race relations and African American cultural history — and to open it in Washington during the final lap of a presidential election as America’s first black president prepares to leave office, during an ongoing period when the GOP had been out for the blood of the Democratic party and while a race-baiting demagogue had already been plastering the headlines — is just a coincidence.

Let me say it more plainly: As the replacement for our nation’s first black president, our country has elected an unapologetic racist. Donald Trump uses a veiled, Nixonian rhetoric in discussions of African American communities, shallowly obfuscating his disparagement of black urban environments by attacking the conditions of the cities themselves, calling them slums, referring to “thugs” that roam their streets. He calls them unsafe for decent people and stokes fear and resentment among rural white men, the group largely responsible for the abuse of black communities that caused them to flee to those cities in the first place.

This is literally what “The Migration Series” is about. And it is a history to which Lawrence was personally tied. Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to parents who had migrated North from Virginia and South Carolina, Lawrence spent his childhood in Philadelphia and Harlem among a continually expanding community of Southern migrants. As a teenager, he became immersed in Harlem’s cultural life and was exposed to modern art, finding sympathy with the politically active work of German Expressionists, Social Realists and Mexican muralists.

In 1940, Lawrence conceived the idea to create “The Migration of the Negro” (now “The Migration Series”). In just under a year, with the assistance of his future wife, the artist Gwendolyn Knight, he realized this epic work, the largest series of his career.

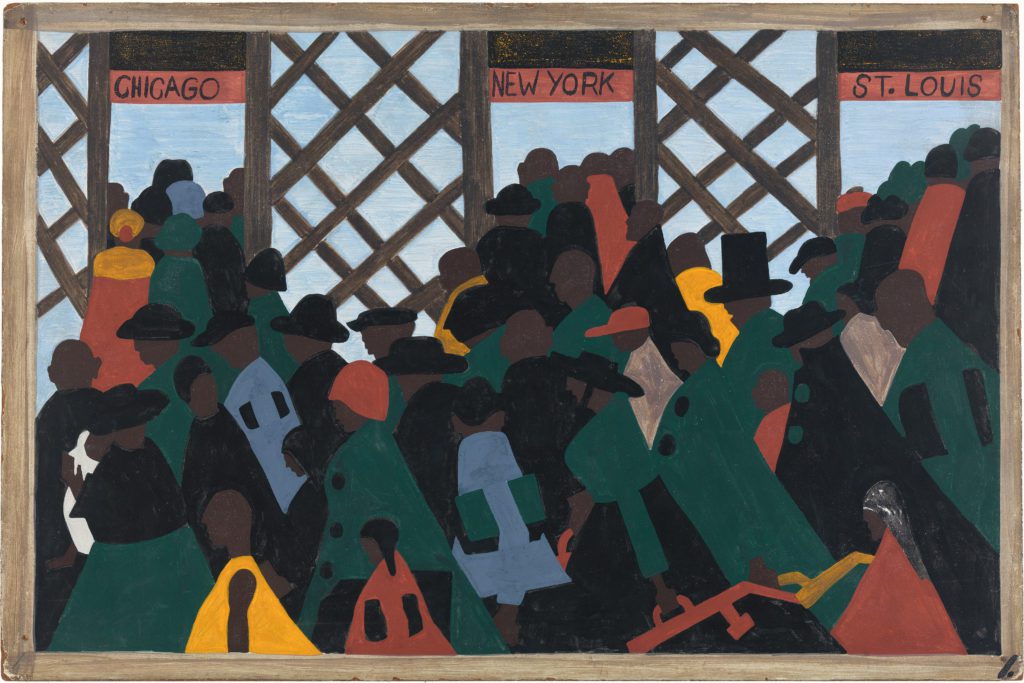

The paintings are stark and geometric, like painted signs or cut-paper illustrations, with a basic palette of no more than five or six colors. The clarity with which Lawrence conveyed such a complex and wide-ranging narrative is truly beautiful, the simplicity of the paintings belying both the ambition of the undertaking and the precision of its execution.

The titles are businesslike, descriptive, more like footnotes than artwork titles. Even without the paintings, reading them in sequence offers a fine idea of the work. The first panel is titled, “During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans.” But the paintings are far more than illustrations of a fairly direct historical narrative; they serve as a window into the emotional experience, the social and logistical struggles and the rich interior lives of midcentury African Americans in the midst of domestic migration.

There is an austere visual poetry to the series. Walls are always bare but for a candle or a skillet. Shapes are flat, faces and bodies painted as single colors. Windows and doors are everywhere, evoking the continual passage into new and evolving environments.

Lawrence drew upon primary accounts he consulted at the New York Public Library and oral histories passed on to him from the Harlem community — street orators, preachers, librarians, teachers, Apollo Theater actors. He also observed their struggles, witnessing firsthand the realities of life in the “Promised Land.”

“To me, migration means movement,” he once said. “There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty. ‘And the migrants kept coming’ is a refrain of triumph over adversity. If it rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.”

Seeing “The Migration Series” reminds us that America has long been a struggle of opposing ideologies that manages to move forward, with an edge toward cultural inclusivity. We do not live in a country that treats all people equally, but through a wide lens it feels like we are, for the most part, trying. It’s a small window of hope right now. But as Lawrence shows us, a small window can be a harbinger of great promise a little farther down the road. We just have to keep moving, and it is inevitable that we also must struggle.