Women Cartoonists at Library of Congress

By • April 4, 2018 0 373

In the past century, I can’t think of two subjects more overlooked in art history than the contributions of women and the influence of cartoons.

A protracted struggle has long existed over the recognition, and perhaps even the understanding, of the influence on fine art of popular, mass-distribution art forms such as cartoons, comic books and magazine advertisements. This probably has to do with the difficulty in accounting for the massive and intricate effects of mass media — which did not seriously exist before the 20thcentury outside of sovereign enterprises — on social psychology and visual literacy over multiple generations.

It also probably has to do with the art-house elite being too proud to acknowledge their more popular, childish, often embarrassing little nephew.

Meanwhile, as in nearly every other profession, women artists have been pushing through professional and social restrictions. It seems achingly obvious to state that in modern-day Western society, men have always dominated most artistic, legal and fiscal occupations.

It is only in the past century or so that women came into the workforce alongside men. From the beginning, they have encountered limitations in training, respect and work environments and a litany of obstacles of every dimension. Nowhere is this truer than in art, which is a fairly inhospitable and cutthroat environment for anyone who tries to move up through its ranks.

Pulling from its invaluable in-house collection, the Library of Congress takes on both oversights in “Drawn to Purpose: American Women Illustrators and Cartoonists.” The exhibition, on view through Oct. 20, brings to light remarkable contributions made by women to the popular art forms of illustration and cartooning, which in turn influenced both fine art and cultural history over the past century.

Spanning the late 1800s to the present, selected works highlight the gradual broadening in both the public and private spheres of women’s roles and interests, addressing such themes as evolving ideals of feminine beauty, new opportunities emerging for women in society, changes in gender relations and issues of human welfare.

Women who first broke into the comics and illustration fields in the early 20thcentury found that publishers — all men — deemed most subjects off-limits to female artists, confining them to a short list of acceptable subject matter: cute babies, cute children, cute animals. Rose O’Neill’s Kewpies (of Kewpie doll fame) and Marjorie Henderson Buell’s “Little Lulu” are notable examples.

Regardless of content limitations, their facility as cartoonists and storytellers is stunning, and seeing work like this on the walls can’t help but leave us yearning for the sawdust scent of a newspaper. There is something heartbreaking about looking at a lost art, and more so at a lost art never properly regarded in its own day.

It wasn’t until Dale (Dahlia) Messick, after a decade of rejections, found a publisher during World War II for “Brenda Starr, Reporter,” her comic strip about a glamorous, strong female journalist, that the landscape for women cartoonists began to widen.

In the later 20th and early 21st centuries, as educational and professional opportunities expanded, women have become leaders in these fields, producing best-selling work, winning top prizes and receiving high acclaim.

I must admit here that it feels uncomfortable to focus on “women artists,” instead of just writing about these women as artists — particularly in regard to those that are still alive and working today. Judging broadly by the body of work on display, these artists rank with their male contemporaries, and though their work can certainly offer a female perspective, the distinction between artwork by men and artwork by women is becoming less defined, in the best way possible.

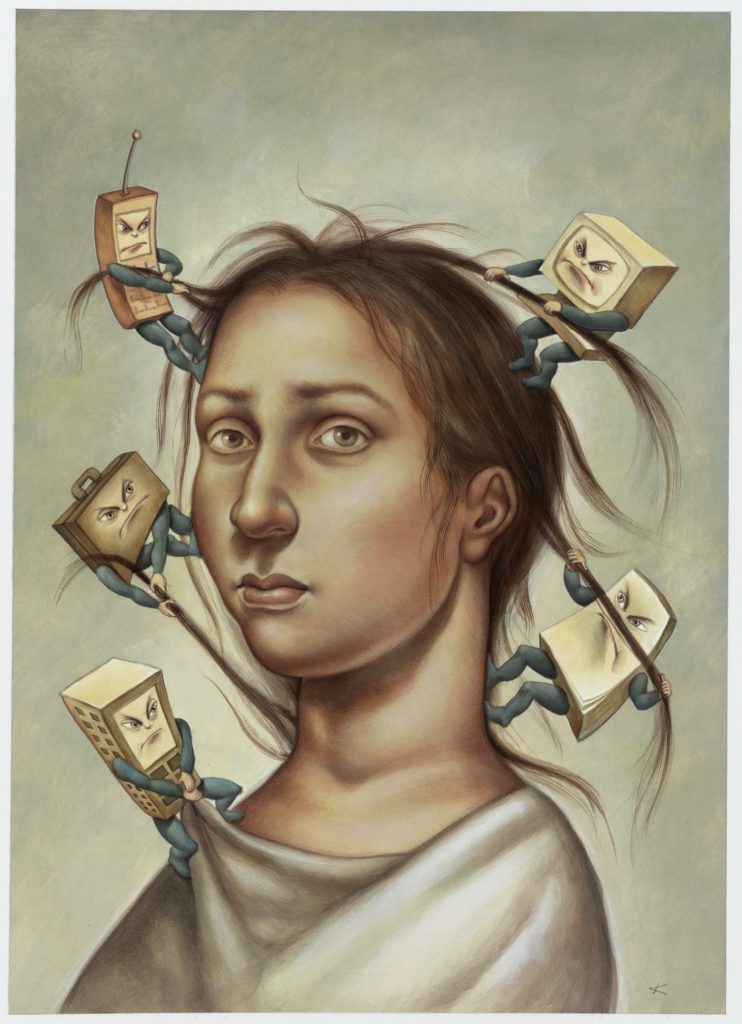

Cartoonist Roz Chast is the closest thing the New Yorker has to a modern-day Saul Steinberg. Ann Telnaes is one of the most profound political cartoonists of the past 50 years. Anita Kunz might be the greatest editorial illustrator in history. Works by all of these women are on display here. All of them will leave indelible marks on history and on anyone who sees this show, and none of this work is gender-specific.

It is not that a man could never do what these women do, nor that these women cannot do what their male contemporaries do. But when someone of a particular identity and background and temperament and gender and age creates something, the result is slightly different than the way any other individual would do it.

What is made clear by “Drawn to Purpose” is that when women are afforded all the opportunities and tools that men are traditionally given to realize their creativity, familiar realms of cultural representation become fresh all over again.

Suddenly we have female cultural perspectives on politics, war, dating, finance, sex, literature, art, men. It is sometimes subtle, sometimes obvious, sometimes imperceptible. And I hope that is the point. Men and women are both different and the same, and our world is richer and more potent when all parties are equally represented.