Reviewed by Kitty Kelley

The Pulitzer-winning reporter recounts the pitfalls of proffering an opinion.

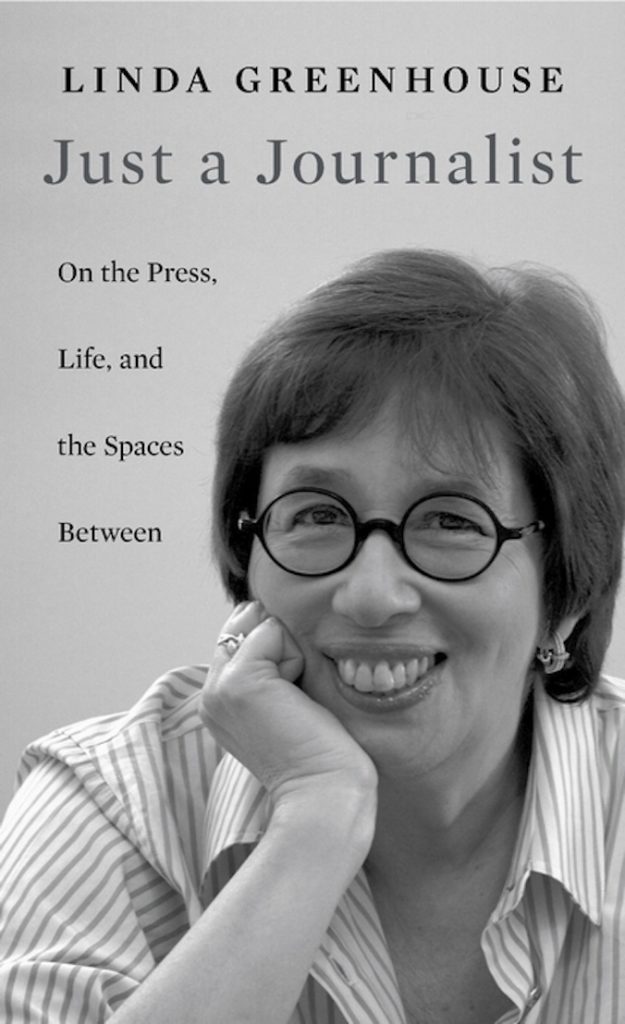

If Linda Greenhouse is “just a journalist,” then Secretariat is just a horse. With a Phi BetaKappa key from Radcliffe (1968) and a Pulitzer Prize (1998) “for her consistently illuminating coverage of the United States Supreme Court” for the New York Times,Greenhouse is the gold standard of journalism.

(Full disclosure: Greenhouse is a friend, and I admire her — personally and professionally. She’s the woman so many would like to be: smart, accomplished and principled.)

Her book, not so much memoir as treatise, took root from a set of lectures she delivered in 2015 at her alma mater. She used herself as an example to pose provocative questions about the shifting boundaries in journalism and whether the old shibboleths remain effective in the 21st century — questions especially prescient now that we’re in the era of “fake news” and “alternative facts.”

Sparking her reflections on the subject was her personal experience following a speech she gave after receiving her college’s highest honor, the Radcliffe Medal. It was 2006, during the second term of George W. Bush, when, she told her audience: “Our government had turned its energy and attention away from upholding the rule of law and creating law-free zones at Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib … and let’s not forget the sustained assault on women’s reproductive freedom and the hijacking of public policy by religious fundamentalism.”

She also talked about how the world had in some important ways gotten better, especiallyin the workplace for women and through the Supreme Court’s recognition of the rights of gay men and lesbians to “dignity” and “respect.”

Greenhouse took heat for expressing herself on these matters of verifiable fact, all part of the public record and covered in depth by the media. She did not reveal state secrets or endanger national security. She simply offered her opinion on the world at that time. Still, her peers pounced.

National Public Radio’s website ran a story headlined “Critics Question Reporter’s Airing of Personal Views.” Among the critics was the Washington bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times, who (like Claude Rains in “Casablanca”) was shocked — shocked! The dean of the journalism school at the University of Maryland pronounced her remarks “ill-advised” and the former chair of the Pulitzer Prize Board’s executive committee said, “The reputation ofGreenhouse’s newspaper is at stake when the reporter expresses her strong beliefs publicly.”

The coup de grace was delivered by her own newspaper’s public editor, who recommended she not cover the Supreme Court on topics she addressed in her speech. “Ms. Greenhouse has an over-riding obligation to avoid publicly expressing these kinds of personal opinions… [and] giving the paper’s critics fresh opportunities to snipe at its public policy coverage.”

They all sounded like Chicken Little, convinced the sky was going to fall on the Times because one of its reporters had expressed herself on public policy. Actually, the sky had fallen two years before, when Jayson Blair was forced to resign for fabricating or plagiarizing half of the 72 stories he had written.

The newsroom was still reeling from that debacle, which may have been why no one stepped forward to defend Greenhouse. To the Times’ credit, she continued covering the court until she retired in 2008, when she accepted an offer to teach at Yale Law School.

Greenhouse blows holes through the current theory of objectivity that journalists are expected to maintain. According to these old rules, journalists should not contribute to their community because it might reflect negatively on their employer or tempt others to see bias in their work. Leonard Downie took this to pious extremes as executive editor of the Washington Post, announcing that he would not vote and would stop having “private opinions about politicians or issues.”

Downie felt that would give him a completely open mind in supervising the newspaper’s coverage, and I suppose it would in Brigadoon. But what about the real world, where journalists might want to participate in parent-teacher associations, volunteer for community organizations, contribute to nonprofits and — God help us — register to vote?

Greenhouse asks how journalists can be objective in their coverage by adhering to “he said, she said” reporting, as if there are only two sides to every story, when, in fact, there are usually several. Under deadline, reporters, trying to be neutral, frequently run to official sources to get their quotes for “on the one hand, on the other hand” presentations. The advocates’ words could be lies (to use the newspaper euphemism, “factual untruths”) or benign lobbying for their particular causes.

If their words come to the reader without context or correction, they gain credibility simply by being quoted in the news. This is the opposite of neutral reporting, since these journalists, striving to be fair and balanced, are, according to Greenhouse, doing what they most dread: deferring to power.

Normally, a journalist writing about journalism is like a golfer writing about golf — interesting only to those who play the game. In this case, though, we’ve got a Babe Didrikson Zaharias holding forth on a subject for which she holds the field, and her subject is not “just” journalism.

While her questions are provocative and meant to be pondered, her style is cool, analytical and without hyperbole. She offers no harsh criticism of her former employer. To the contrary, she recognizes the premier position the New York Times holds and wants nothing more than for the “paper of record” to excel in its mission to inform.

Journalism affects all of us — locally, nationally, internationally. Journalists are our eyes and ears, and without seeing and hearing we’d be blind and deaf, unable to function. Linda Greenhouse’s little 192-page book is a big contribution and deserves our attention.

Georgetown resident Kitty Kelley has written several number-one New York Times best-sellers, including “The Family: The Real Story Behind the Bush Dynasty.” Her most recent books include “Capturing Camelot: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the Kennedys” and “Let Freedom Ring: Stanley Tretick’s Iconic Images of the March on Washington.”