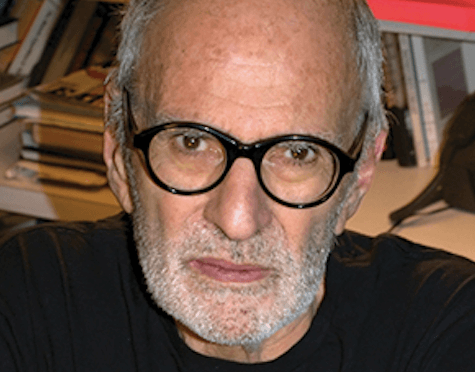

Author and Agitator Larry Kramer Dies

By • May 28, 2020 0 1252

As an author, Larry Kramer, who died on May 27 at age 84, was best known for “The Normal Heart,” a play about the early years of the AIDS epidemic. It was originally staged at New York’s Public Theater in 1985, as the horrific deaths of gay men continued to mount.

If you saw that production, one of the later ones — notably the Tony Award-winning revival that came to Arena Stage in 2012 — or the 2014 HBO film, you were schooled about Larry Kramer’s other calling: agitator.

Scornful, unrelenting, needy, devoted Ned Weeks, the pissed-off prophet in “The Normal Heart” who thrashes around, trying to wake up his people (so to speak) and force New York and Washington to act — that was Kramer.

Weeks, like Kramer, held argumentative meetings in his apartment that led to the creation of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was later kicked off the GMHC board as a loose cannon (also for his support for outing closeted gays in influential positions). In 1987, Kramer went on to found ACT UP, AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power, an agitprop group that demonstrated and disrupted under the banner “Silence = Death.”

Other characters in the play and the film, for which Kramer wrote the screenplay, were based on particular individuals, including Kramer’s homophobic older brother. The alarmed, pioneering doctor Emma Brookner, played by Julia Roberts in the film, was inspired by Linda Laubenstein, like Brookner confined to a wheelchair by childhood polio. (Early on, while examining Weeks, Brookner mentions his “big mouth.” “Is a big mouth a symptom?” he asks. “No, it’s a cure,” she says.)

Weeks’s head-turning young lover, New York Times style columnist Felix Turner, who disintegrates before our eyes, was said to be modeled on John Duka, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1989. Below the original review of “The Normal Heart” in the Times, written by Frank Rich, ran a denial of Kramer’s accusations that the paper had played down its coverage of AIDS.

Kramer, who was raised in Mount Rainer, Maryland, and graduated from D.C.’s Wilson High School, then Yale, began his career as a screenwriter. After working on films in England, he bought the rights to D. H. Lawrence’s novel “Women in Love,” adapted it, hired Ken Russell to direct and, in 1969, had a hit to his credit. A bomb — a 1973 musical remake of Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon” — followed, but his pay for the screenplay was a windfall.

He then wrote a novel, “Faggots,” which depicted — truthfully, said Kramer — the 1970s gay culture of discos and bathhouses. With its tone perceived by many in the gay community as anti-gay, the book’s author was shunned as an out-of-touch moralizer.

Then came what was initially referred to as “the gay plague” and “GRID,” for Gay-Related Immune Deficiency. The crisis took possession of Kramer, as it did San Francisco Chronicle reporter Randy Shilts, who wrote “And the Band Played On” about its mishandling in 1987.

When Weeks is abruptly removed from the board of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, he refers to World War II code-breaker Alan Turing, a gay man who, by most accounts, killed himself in 1954 following his conviction for the then-crime in England of gross indecency: “That’s how I want to be remembered. As one of the men that won the war.”

Though Kramer lived to legally marry his longtime partner, David Webster, in 2013 (a wedding item appeared in the Times), he did so in a hospital while recovering from surgery. His health was poor. At first denied a liver transplant because he was H.I.V.-positive, he was able to obtain one in 2001. Kramer did not, however, develop AIDS. The cause of his death was pneumonia, according to Webster.

Kramer remained pessimistic about the prospects for gay equality in the U.S. until his death. He never claimed victory in his war, but he will be remembered as someone who made a difference — and not only for the LGBT community.

A household name during the current pandemic, Dr. Anthony Fauci, who was a target of Kramer’s bitter criticism in the 1980s, was quoted years later in the New Yorker: “In American medicine there are two eras. Before Larry and after Larry.”