At the Hirshhorn: Kusama’s ‘One With Eternity’

By • April 13, 2022 0 1510

By this point, I’m assuming you know Yayoi Kusama. She’s a global phenomenon, one of the most celebrated artists alive, and an unlikely fashion icon. Her immersive Infinity Rooms are probably the most popular and perfect art objects of the social media era (even though most of them were made before smart phones existed). She herself is also perfect for this moment: a severe-looking, ancient Japanese woman with a fire-engine red bob (I’m guessing it’s a wig, though I refuse to research this topic), who makes her own clothes to match her art installations. She’s a walking meme.

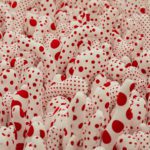

Last month, my wife and I took our 11-month-old daughter to the press opening for the Hirshhorn’s new Kusama exhibition, “One With Eternity.” I think we expected — certainly, we hoped — that our baby would beam with astonished amusement at Kusama’s wonderlands of colors and shapes. What baby wouldn’t delight in endless landscapes made entirely of their favorite things — shiny lights, hanging baubles, plush shapes, pumpkins, polka dots and moonbeams?

My daughter’s actual reaction radically changed my perspective on Kusama and her work — she was not delighted. She was in turns anxious, tense, curious and confused. I wouldn’t have called her entirely unhappy, but this was decisively not a rapturous experience.

Kusama’s Infinity Rooms have been made into funhouses, but I don’t believe she intends them that way. If you look closely — say, through the eyes of a baby — they can be manic, disorienting, unsettling and vertiginous.

“Now that we find ourselves on the dark side of the world,” Kusama said in a recent statement, “The gods will be there to strengthen the hope we have spread throughout the universe…. The time has come to fight and overcome our unhappiness.” Her work may be full of joy, but it is in deadlocked mediation with abject terror.

Born in 1929 in the Nagano prefecture in Japan, Kusama began experiencing visual and auditory hallucinations at age six, which she channeled almost immediately into art. At age 15, she was mobilized along with other young women to work in a parachute factory for Japan’s war machine. She describes the constant American air raids during that time as paralyzing to the point that “I could barely feel my life.” She came into her career and adulthood in the wake of a world war and two atomic bombs.

On the one hand, you can draw a very clean line from Kusama’s Infinity Rooms — hermetic, endlessly refracting alternate universes of delirious, technicolor chaos — to atomic fission, the splitting of atoms. But I don’t think that does the artist justice.

Kusama seems divinely cursed with the need to create. Her life has been one continuous ritual of transcribing hallucinations onto ever-grander scales. Her early paintings, a small example of which is featured in this exhibition, are just as haunting and infinite as an Infinity Room, if less dimensional. She’s a true artist and a compulsive creator, and her work is that of a beautiful but troubled mind.

It’s worth knowing that Kusama has been living voluntarily in a hospital for the mentally ill in Tokyo since 1977. This often gets glossed over, as if it’s a minor detail (“all artists are crazy!”), but it’s not and it shouldn’t be. There is beauty and tragedy here, genius and madness. Hers is the life and work of a woman who has fought her demons to a stalemate by distracting them with infinite beauty.

Go to this show, try to keep your phone in your pocket, and do what my daughter did, what I imagine Kusama does every day: keep your eyes open, your mind free of judgment and your heart on your sleeves, and let it all rush through you.

“One With Eternity: Yayoi Kusama in the Hirshhorn Collection” runs through Nov. 27.

Click the photo icons below for a slideshow of our photos from the exhibit.

- Photo by Jeff Malet.

- Yayoi Kusama’s Pumpkin (2016). Photo by Jeff Malet.

- My Heart is Dancing into the Universe (2018). Photo by Jeff Malet.

- Infinity Mirror Room: Phalli’s Field. Photo by Jeff Malet.

- Photograph of the artist with signature polka dots. Photo by Jeff Malet.

- Yayoi Kusama Flowers – Overcoat (1964). Photo by Jeff Malet.