Rex Carnegie: Putting Together the Ideal Learning Experience on the C&O Canal

By • June 1, 2023 0 1366

Imagine the perfect learning experience. All the senses engaged in hands-on activities. A sense of awe and wonder nurtured in deep discussions with critical thinking skills sharpened. Deep social historical understanding combined with scientific learning interwoven to create an unforgettable, entertaining and joyous experience.

Unrealistic, you say? Not on Georgetown’s new C&O Canal boat under the guidance of Rex Carnegie, director of education and partnerships for Georgetown Heritage.

The canal boat tour runs from Lock 3 in Georgetown to the Aqueduct and back, one mile in one hour. Photo by Chris Jones.

The Georgetowner spoke with Carnegie about his development of such a rich curriculum so well suited for all audiences and delivered by period-costumed performers – himself in the leading role – aboard the new canal boat, “The Georgetown Heritage,” during its one-hour one-mile floating tour from Lock 3 in Georgetown to the Aqueduct and back. The tour teaches passengers about “the fascinating history, technology and culture of the C&O Canal, and the surprising stories of the people who lived, worked and played [there] over the past two centuries.”

Carnegie was “born and raised in D.C. and Prince George’s County,” and described his winding pathway to his current role. “I came at this type of work in a little different way because I have an arts background,” he said. At Loyola College he “studied theater and [has] been a practitioner of theater arts, dance, music, all the performing arts. So, I fell into doing educational work through arts education at the Smithsonian.” Carnegie led several projects for Smithsonian museums and rose to serve as the creative director at the American History Museum.

Carnegie has also created arts programs for the Kennedy Center, the White House, the National Park Service, the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center, the Library of Congress and the Department of Justice as well as serving as a professional TV host, live MC, presenter, panel moderator and voice-over artist.

To create the curriculum for the C&O Canal boat tours, Carnegie and his partners at Georgetown Heritage researched deeply into primary source materials to find the true voices of the historic and present-day canal experience. They also scrutinized both the social studies and science learning standards for the D.C., Virginia and Maryland school systems.

And Carnegie loves the material they found. “What’s great about this is that it hits on local, regional and even national history,” he said. “So, that’s kind of wonderful to teach people about our local history here in D.C. But also to see how it connects to other things they might have heard as they were studying or looking at things such as the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad or western expansion and all of those sorts of areas.”

Rex Carnegie in period dress aboard ‘The Georgetown Heritage.’ Narrative story-telling from primary sources enlivens the curriculum. Photo by Chris Jones.

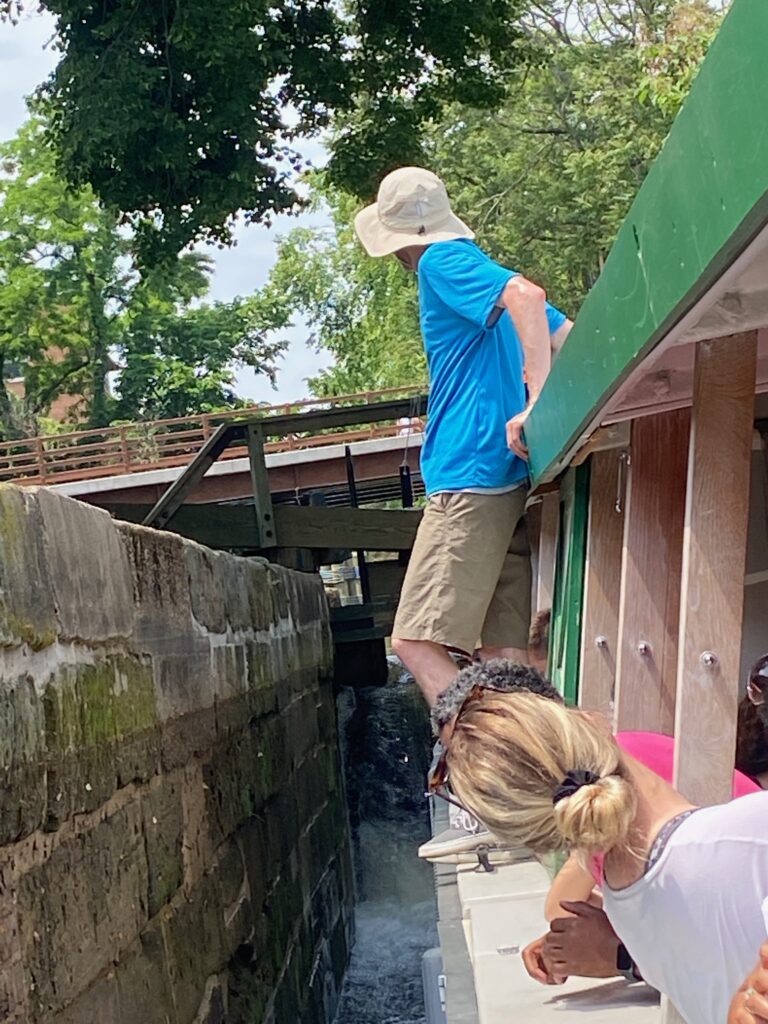

But the C&O Canal also presents great opportunities for STEAM education (science, technology, engineering, arts and math). Watching the boat hands control the locks to the canal to raise or lower water levels is a fantastic way to learn about a variety of lessons in physics and fluid mechanics. “Our main STEAM activity or experience is the lock itself. So, we do spend a little time [onboard] talking about what a lock is and how we work it and then for students we can talk a little bit more about the principles that go in behind it – whether that’s water pressure or fluid dynamics or gravity – all of which play a part in that 200-year-old lock mechanism – or really 500-year-old lock mechanism because it was originally designed by Leonardo Da Vinci – So, there’s really a great connection there…. It’s so much fun.”

STEAM education is provided by studying the physics and fluid mechanics of the canal’s lock mechanisms. Photo by Chris Jones.

Another cutting-edge aspect of the curriculum is the use of open-ended, guided questions to stimulate intergenerational dialogue and to engage passengers’ imaginations. “I don’t want to get too nerdy with this – but, as someone who’s done a lot of museum education and a lot of informal learning in arts and education, there’s this tendency for folks to say, ‘Oh, well, this is just for the kids.… We’ll just give the adults a chance to check out… But, that’s something that’s actually hurt the field, to be honest with you,” Carnegie said. “We wanted to make sure that everything we’re doing and everything we’re saying has something for all audiences that people in a wide range of age groups could get something out of. …During the program we ask questions that we hope will spark conversation across generations. So, when we’re talking about the Civilian Conservation Corps, there are people who are still alive who remember a little bit of that, or they remember their parents doing it. And they can talk to the younger generations about what they said that was like. And now we have this kind of exchange that’s happening across generations…. Now we realize that everybody has a voice in this. It’s very similar to how with the canal there was a very diverse range of people from all different backgrounds, all different ages, all different cultures that helped to make this place what it is.”

One of the characteristic features of the canal boat tour is the dramatic readings historical re-enactors perform from primary source texts. These are designed to delve deeply into real people’s experiences along the canal or aboard a canal boat from the pre-Colonial 17th-century world of Native Americans and from the early 19th century when the canal was built (starting in 1828) to the present. “Primary sources are the cheat-code for informal education,” Carnegie said. “Hearing history in someone’s own words is so invaluable. You know, in these programs, we talk a lot about the places and the names and the dates. But really what they’re about is feeling. It’s people in a place and time who were feeling something and so because of that they ended up doing something… So having that primary source, it brings it alive in a way that connects people, I think, across the years – across hundreds of years to the feelings and emotions that this person had. So, whether there’s a little bit of humor in it, whether it’s a little frightening or there’s something profound, these primary sources really do speak to us across the years.”

Developing primary source readings into strong narrative story-telling serves as another effective approach to teaching.

One of Carnegie’s favorite stories of the many he dramatizes during the tour came from the oral history interviews with Ted Hebb conducted in the 1990s. Hebb grew up on the canal and lived to be quite old, so he was able to reach back into the 19th century to recount some “rough characters on the canal,” Carnegie said. “And the part we highlight on the boat is when he talks about … what they ate on the canal…. the two [foods] that were kind of standouts, were that they would eat eel and they would stew turtle.” And Hebb described “how they would prepare the eel, how they would still be jumping in the pan when they were frying them. So, for us it’s got that gross factor but at the same time it’s really got that cool, if you were on the canal this is something you might have to do aspect…. So it was just such a great off-the-cuff interview that really covers all the sensations and feelings we want to get across.” Plus, it makes folks wonder about what animals might still be thriving in the canal environment today. Seen any eels lately?

Appealing to all the senses is another powerful curricular strategy for enhancing learning.

Obviously, being out on the water, gathering in all the rich scents of the canal and the Potomac river, the birds, the distant sounds of the city are inherent in the experience. But, other more subtle cues are also in the mix. “We don’t have the mules [yet], so we haven’t got the smell quite as we want it [laughs], but I think either with the leather on the harness or the smell of that coal or the distinctive smell of that metal lock key or even the straw from our hats, something as simple as that can all appeal to the senses. So that makes a big difference,” Carnegie said.

Another fortunate aspect of the curriculum, Carnegie said, was that lessons in gender, racial or economic diversity flow naturally from the canal’s actual history.

“Most of American history is diverse because from the inception people from many different nations made this land what it is. So for me – and obviously, being African-American – the diversity part of this is so easy because we are diverse,” Carnegie said. “It’s a part of our identity. And I think that one of the issues, particularly with history, is that there’s this erasure that happens where we try to make things look less diverse than they are, or feel less diverse than they are, but really all of these things are part and parcel of learning anything about the area.” On the canal tour, some of the the most surprising learning comes from guessing the names of a roster of 19th-century canal boat captains and then finding out so many were women or African-Americans. “These folks were here and had to be here and without them it’s very likely a lot of these locks wouldn’t have been manned and a lot of these goods wouldn’t have gone back and forth…. It isn’t that we’re ‘trying to be diverse.’ The story of the canal is diverse. And we owe it to that history and to those folks to tell a broad spectrum of their stories.”

During a canal boat tour, it’s clear that children and adults love the hands-on aspects of the curriculum. Historical artifacts and tools are passed around so passengers get a sensation and feel for what people experienced historically and even what today’s crew members’ jobs are like.

“What’s great about it is that a lot of these ‘touch-objects’ are still being used,” Carnegie said. “So a lock-key is something we use on this canal in order to drain it, in order to make sure it’s well-preserved in order to do our boat operations. So giving people a sense historically of not only what people might have had to use, what they might have touched, what they might have moved, but also the fact that a lot of these things, people are still dealing with them today. You know, whether it’s the blacksmith who’s made our lock keys or the farmers who use yokes and harnesses or even something as simple as coal.” Though the color of the coal has changed, holding it in your hands allows you to understand “it’s the stuff that helps make our nation.”

An historical interpreter passes around a harness to enhance hands-on learning. Photo by Chris Jones.

What really delivers, however, is the combination of sheer joy both passengers and crew experience while aboard combined with the critical thinking nurtured. “There’s just a lot of fun to it,” Carnegie said. “It’s such a singular type of experience. But also, I think critical thinking is so key to education. And one of the things we want to make sure we’re doing is that we’re posing questions to students that really get them to think and play out things in their heads. Not just necessarily to remember a certain date or a certain event but also to think about how that event is relevant by putting themselves in the shoes of folks in history. And we do that with each talk-back question we’ve designed for each section of our tour…. And for me the real joy has been in watching them discuss things we bring up. Seeing them kind of work out for themselves, you know, ‘If that had been me, how might I have done it?,’ Or, ‘Is there a way for them to innovate?’ Or, ‘Is there something surprising here?’ …. That for me is sort of the joy of informal education.”

For C&O Canal Boat tour information, visit Georgetown Heritage.