Celebrating Dr. King’s Abiding Spirit

By • January 21, 2019 0 863

Sometimes we forget. Sometimes, here at the center of the world, everything happens at once.

We, the residents of Washington, D.C., are enduring a partial government shutdown. On Friday, Jan. 18, we saw the March for Life, actively in opposition to the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision of 1973 that decriminalized abortion nationwide.

On Saturday, Jan. 19, there was the third Women’s March, celebrating the increasing power of women as voters, as members of Congress, as a political force in the United States of America. It was not quite so large, so pink or so united as previous Women’s Marches, but nonetheless majestic and impressive and inspiring in its presence.

In other words, last weekend the town was full of the cries, assertions and energy of sometimes competing forces, battling bitter, wet, occasionally snow-filled weather and other obstacles, including another speech by President Donald Trump on the shutdown.

We forget. Today, Monday, Jan. 21, notwithstanding all that occupied us so strongly over the weekend, we celebrate.

We celebrate the birthday of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., as we have done every year for a number of years now. The birthday is, after all, a national holiday, presided over by the warming, imposing statue of King himself, and the memory of his abiding spirit, which, in this town, is never so distant as to be forgotten entirely.

Mayor Muriel Bowser spoke at a National Action Network breakfast at the Mayflower, took part in a Day of Service pep rally in Northeast, then marched in the 38th annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Parade in Southeast.

Tonight, we can celebrate Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy through music by attending a tribute at the Kennedy Center, “Let Freedom Ring!” Audra McDonald and Brian Stokes Mitchell will perform with the Let Freedom Ring Choir at this free concert in the Concert Hall at 6 p.m., part of the Millennium Stage series, in collaboration with Georgetown University.

Today, and tonight, though, most of us, one way or another, will hold Dr. King’s memory dear and close to heart — as memory, as a voice, as words and thoughts, both visionary and practical, uttered in an atmosphere of danger, with the practice and stride of great courage, because the man and his vision changed the country and the world.

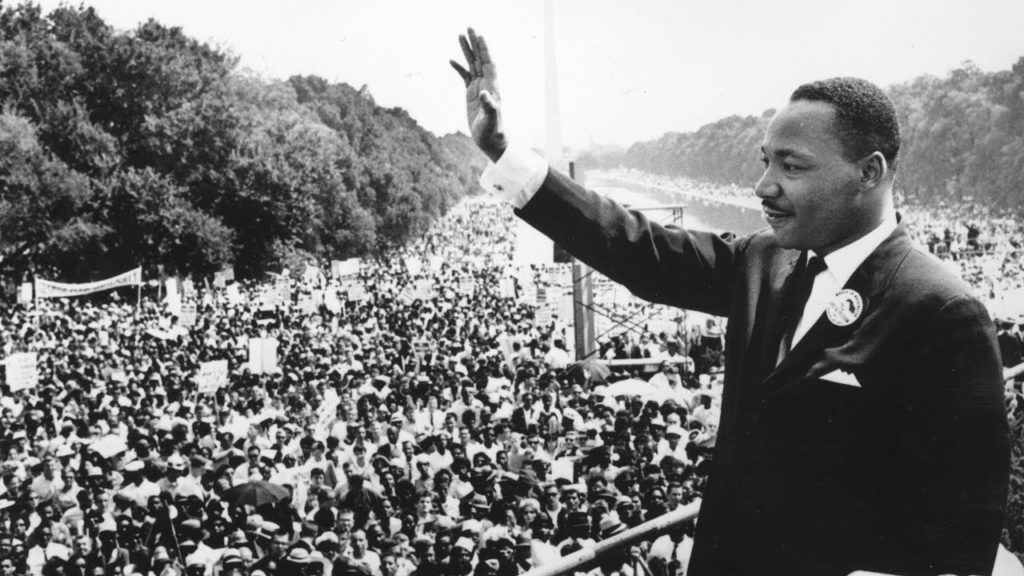

We remember the marches, the thousands upon thousands of people on the National Mall, hearing words tossed into the air and day with the certitude of hope, and the hope retained. We all remember that speech, even if we were not there among the multitudes that seemed like millions, because he could say “I have a dream” and be believed that day.

What followed eventually was change, the tumultuous days of protest and violence and lunch counters and dogs loosed and signatures on signature civil rights legislation, the days of “parting the waters,” as one history of King and the civil rights movement declared.

We remember all that and the day of his death, too — shot on a balcony in Memphis, where he had come to lead a protest with striking sanitation workers.

We remember less the speech the day before, on April 3 in 1968, the year of violence and death, parts of Washington and other cities burning in the wake of King’s assassination, the Tet Offensive, the forever war, the protests at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, the shooting of Robert Kennedy in a hotel kitchen in Los Angeles.

It was the “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, which, like the “I Have a Dream” speech, had a quality on paper and, we would guess, in the speaking, of pure and purely rhetorical power. It invoked the Bible and the prophets, as if he were indeed not just a pioneer but a forerunner, not destined to live forever.

With Ralph Abernathy — the man whom King deemed to be his best friend and who would lead the Poor People’s Campaign — nearby, he said: “Something is happening here in Memphis; something is happening in our world.”

He embarked on what amounted to a voice journey through time, imagined but real nonetheless. “If I were standing at the beginning of time … and the Almighty said … which age would you like to live in,” King said he would “watch God’s children … across the Red Sea, through the wilderness on toward the Promised Land.”

But, he said, “I wouldn’t stop there,” moving on to Greece, on to Rome and its heyday. “But I wouldn’t stop there,” he said, proceeding to the Renaissance. “But I wouldn’t stop there.” He would go and see the habitat of his namesake Martin Luther. “But I wouldn’t stop there.” He described continuing on to Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation, and to the 1930s, when a man said we have nothing to fear but fear itself.

But he did not stop there, instead preferring to be where he was in the latter part of the 20th century, because “Something is happening in our world.” All over the world, “the cry is always the same: ‘We want to be free!’”

He went on to talk about the issue: injustice. And he recalled the spirit of the marches of the 1960s, of dogs set on men, churches and bullhorns, when he and others sang: “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around.”

Like some settled magician, he went on and on, concluding: “It doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind … And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people will get to the Promised Land. And so I’m happy, tonight … I’m not fearing any man!”

The next day, he was killed.

The world is different because of him. That’s what we remember. Its contours may not be those of the Promised Land, not yet, but its shape, as in the dream he had, can be discerned. He was never going to stop there.