The Life of Georgetown From 1620 to 2020, Part 2

By • December 28, 2020 0 3866

It seems fair to say that most Georgetowners think of 2020 as the worst year in memory. This annus horribilis seems destined to be remembered as the year of the pandemic, the damages from the protests, school closures, the slumping economy and the increasingly partisan — if not dangerous — political divide in our nation’s capital.

However, a look at Georgetown’s history may help to keep our challenges in perspective. From its beginnings, Georgetown has handled wrenching changes with resilience. As the nation has expanded and transformed, Georgetown has adapted to hardships and flourished.

Here is the second of three looks into Georgetown’s past, focusing on the years around 1820. [Note: 1920 will appear in an upcoming newsletter.]

1820

By 1820, Georgetown life was accelerating rapidly due to powerful national and international trends. Following the American Revolution and the adoption of the U.S. Constitution by 1788, the new Federal City was moved in 1800 to its present site in the District of Columbia, adjacent to Georgetown (incorporated in 1789) and just upstream from George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate.

According to local folklore, George Washington met in 1791 with local landlords at John Suter’s tavern in Georgetown to plan the new Federal City. Suter’s son, John Suter Jr., rented the first floor of the Old Stone House at what is now 3051 M St. NW, the only surviving pre-Revolutionary building in Georgetown.

Designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1791, the layout of the new capital, with its grids, diagonals and grand thoroughfares, reflected both the rationalism of the Enlightenment and a masterful plan for the city’s growth while creating sweeping vistas to capture the area’s scenic beauty.

In the first U.S. Census, taken in 1800, Georgetown’s population was recorded to be 5,120, including 1,449 enslaved persons and 227 freemen. Around 1800, when the federal government began to occupy unfinished buildings along a network of unpaved streets, Georgetown was the most civilized and prosperous section of the embryonic city. Fortunately for Georgetown, its economy continued to strengthen through its attachment to the new national capital, despite the decline of its port due to heavy silting of the Potomac River and reductions in the tobacco trade.

During Jefferson’s presidency, from 1801 to 1809 — the first in the new capital — the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 doubled the size of the country and Jeffersonian agrarian populism swept away Hamiltonian federalism. For the Native Americans, however, Indian removal soon followed.

In the wake of the French Revolution (inspired in part by the American Revolution) and Napoleon’s rise to power, the United States was drawn into a major European war, siding with Napoleon’s France and against its former adversary, Great Britain, in the War of 1812. In 1814, the British invaded Washington, D.C., burning the U.S. Capitol, the Treasury, other public buildings and — most ominously — the President’s House, requiring President James Madison and first lady Dolley Madison to flee to safety.

At Dumbarton House in Georgetown, built in 1799 and then known as Belle Vue, owner Charles Carroll aided the Madisons when the British attacked. “Our kind friend, Mr. Carroll, has come to hasten my departure, and is in a very bad humor with me because I insist on waiting until the large picture of Gen. Washington is secured, and it requires to be unscrewed from the wall,” wrote Dolley Madison as she awaited her husband’s return. “And now, dear sister, I must leave this house, or the retreating army will make me a prisoner in it, by filling up the road I am directed to take.”

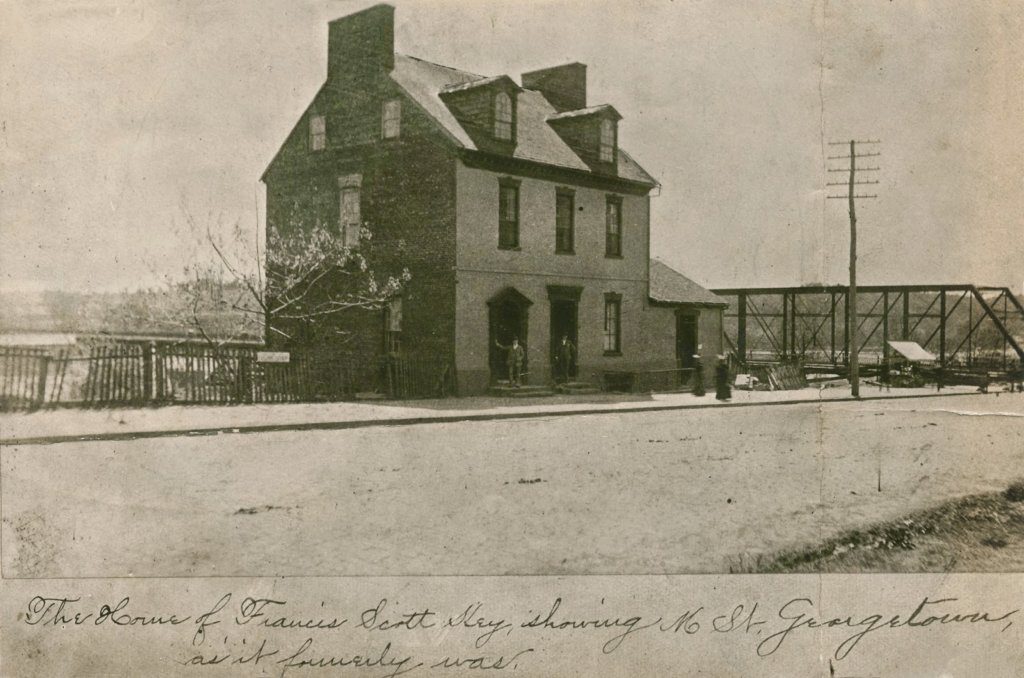

In September of 1814, the British failed to capture Fort McHenry in Baltimore after the burning of Washington. Francis Scott Key, whose Georgetown home stood at 3518 M St. NW until its dismantling in 1947, famously penned the lyrics to the “Star-Spangled Banner” while a captive of the British in Baltimore. Returning to Georgetown after attempting to free his uncle from captivity, Key was persuaded by his friends in the Georgetown Glee Club to write lyrics about his experience. His composition was read at the club’s next meeting.

Soon after the war, the United States entered a period of rapid rebuilding, industrialization, patriotic nationalism and territorial expansion. By 1817, President Monroe was welcomed back to a newly reconstructed and expanded White House. Congress moved into its rebuilt facilities by 1819 and the following year saw the completion of Washington’s new City Hall.

By the 1820s, the American Industrial Revolution was taking off, making a visible impact on Georgetown. In 1828, construction began on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, linking Georgetown’s commerce to the west. The canal building boom, however, would soon give way to the mania for railroad building, with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the nation’s oldest, starting up by 1830.

By 1820, Abolitionism had arrived in the halls of Congress as well as in the nation’s capital. In the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Congress negotiated a line of latitude above which slavery was meant to be prohibited. Battles over slavery were also fought in D.C. in the coming years. At Mount Zion United Methodist Church on 29th Street NW in Georgetown, built in 1816, the Underground Railroad operated a secret “station” for runaway slaves fleeing north.