Mikhail Gorbachev (1931-2022): An Appreciation

By • September 1, 2022 0 2576

With the Aug. 30 death at age 91 of Mikhail Gorbachev (1931-2022) — the last leader of the Soviet Union before its dissolution at the end of the Cold War — a predictably wide range of accolades for and denunciations against the transformative communist head-of-state who led the most expansive land empire in world history from 1985 to 1991 have proliferated across world news platforms.

Many have praised Gorbachev’s broad reformist vision citing his introduction of liberal democratic elements into the Soviet totalitarian system while promoting free expression, helping liberate the captive nations of eastern Europe, reducing Cold War tensions and drastically lessening the risk of nuclear war between the superpowers.

“Mikhail Gorbachev was a one-of-a-kind statesman who changed the course of history,” wrote the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, yesterday in a tweet. “The world has lost a towering global leader, committed multilateralist, and tireless advocate for peace. I’m deeply saddened by his passing.”

“We mourn the passing of Mikhail Gorbachev, a man whose openness changed the course of human history. He never lost faith in the transformative power of engagement and dialogue and his life is a powerful reminder of all that can be achieved when we make those ideals a reality,” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken wrote yesterday in a tweet.

“Mr. Gorbachev performed great services but he was not able to implement,” assessed former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in an interview yesterday with the BBC. “He was in part destroyed by developing ideas for which his society was not yet fully ready… But the people of eastern Europe, the German people, and in the end, the Russian people owe him a great debt of gratitude for the inspiration, for the courage, in coming forward with these ideas of freedom and even though he did not prove strong enough to resist the passions that he unleashed, he performed a great service to humanity.”

Yuval Noah Harari, author of “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind,” offered even higher levels of praise: “He renounced more power than any other person in history, and by doing that he saved more people than any other person in history.”

Many others, however, have sought to portray Gorbachev as a diehard Marxist-Leninist Communist Party official who misread the forces of history, bumbled his way through a series of doomed half-measures, offered reforms to the Soviet system only to prevent its downfall and then soaked up lavish praise from the west for helping it win the Cold War. “Almost nobody in history has ever had such a profound impact on his era, while at the same time understanding so little about it,” tweeted Pulitzer Prize-winning Cold War historian Anne Applebaum yesterday of Gorbachev.

In “The Cold War: A New History,” historian John Lewis Gaddis summarized Gorbachev’s legacy as bumbling but profoundly influential and deserving of praise nonetheless. “Gorbachev dithered in contradictions without resolving them. The largest was this: he wanted to save socialism, but he would not use force to do so. It was his particular misfortune that these goals were incompatible — he could not achieve one without abandoning the other. And so, in the end, he gave up an ideology, an empire, and his own country, in preference to using force. He chose love over fear, violating Machiavelli’s advice for princes and thereby ensuring that he ceased to be one. It made little sense in traditional geopolitical terms. But it did make him the most deserving recipient ever of the Nobel Peace Prize.”

With the complexities of history, a wide-eyed embrace of Gorbachev’s complete record is, of course, naive. But a failure to appreciate his unprecedented achievements is equally, if not more dangerously so.

The tension between praising and damning Gorbachev’s legacy played out in a fascinating way on the editorial pages of yesterday’s Washington Post. “Mr. Gorbachev opened the door; He set out to save his country but changed the world instead,” wrote the paper’s editorial board. The changes Gorbachev wrought were “astonishing,” they assessed. Gorbachev “opened intellectual life and lifted the veil on much of the Soviet past – on the cruelty, violence and savage repression.” He “brought about the first relatively free election since the Bolshevik Revolution in voting for a new Soviet legislature in 1989, the Congress of People’s Deputies.” He insisted the proceedings be televised. And, the “Communist Party took a shellacking.” The country “was transfixed by debates that broke new ground in freedom of speech.”

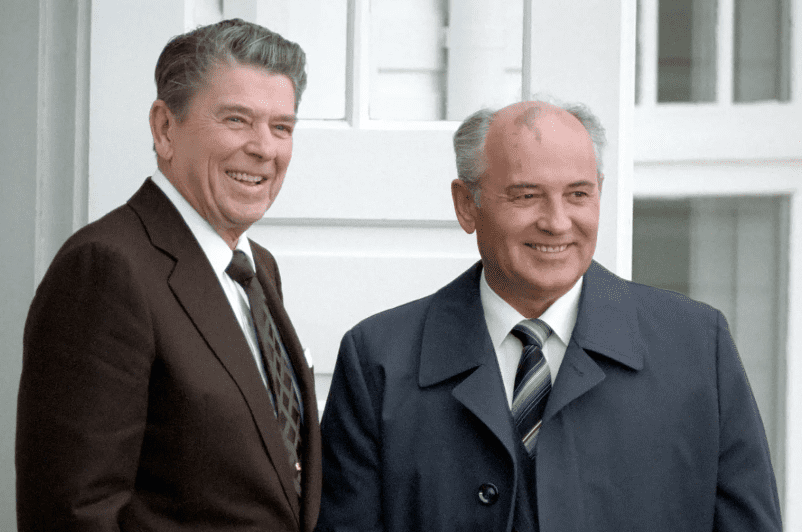

Though Gorbachev “often miscalculated,” the Post wrote, his arms control summits with President Ronald Reagan “electrified the world and led to sizable reductions in the mountains of nuclear warheads.” While Gorbachev didn’t perceive the centrifugal forces created by his reforms triggering break-away republics and the collapse of the Soviet empire, “his legacy made the world safer. He helped brake the speeding locomotive of the arms race and allowed a peaceful revolution to unfold in Europe. For these and other accomplishments, he deserved and won the Nobel Peace Prize.”

Positioning himself as ever-the-staunch Cold War realist, however, columnist George Will wrote yesterday that Gorbachev “stumbled into greatness by misunderstanding where he was going” likening him to a Christopher Columbus “accidentally discover[ing] the New World.” Citing Gorbachev’s biographer William Taubman, Will informs readers that Gorbachev once denounced Soviet political dissident and Refusenik Natan Sharansky as a “turd” and a “spy” in response to a proposed toast to Sharansky from British Labour leader Neill Kinnock. “Gorbachev’s reputation rests on amnesia,” the headline of Will’s column declares.

Adjacent to Will’s column in yesterday’s paper, however, Natan Sharansky — who was freed as a political prisoner in the Soviet Union by no other than Gorbachev himself in 1986 — wrote his own thank-you to the Soviet Union’s last leader. Sharansky credited Gorbachev — the Soviet Union’s first and last president — with “understating” the leader’s historic achievements when he stepped down as president in 1991. Gorbachev’s legacy was more than simply promoting “political and religious freedom, the introduction of democracy and a market economy” as well as ending the Cold War, Sharansky argued.

“Just a few years earlier, the Soviet Union had been one of history’s most frightening dictatorships, sending its troops far and wide, ruling over roughly one-third of the globe, and controlling hundreds of millions of its own citizens through intimidation,” Sharansky continued. “And while Soviet dissidents (I was among them) told the world that the regime was internally weak, our predictions of its downfall were dismissed as wishful thinking…”

From the “birds-eye perspective of history,” Sharansky concluded, “we see how utterly unique Gorbachev was. In nearly every dictatorship there are dissidents, and from time to time there are also Western leaders willing to risk their political fates to promote human rights abroad. But Gorbachev was a product of the Soviet regime, a member of its ruling elite who believed its ideology and enjoyed its privileges — yet decided to destroy it nevertheless. For that,” Sharansky ended, “the world can be grateful. Thank you, Mikhail Gorbachev.”