Kitty Kelley Book Club: ‘The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Created a President’

By • August 14, 2024 0 1079

Edward F. O’Keefe argues that five women provided the ballast of Roosevelt’s life.

The huge granite sculpture startles tourists. Looming like a ferocious behemoth — intimidating, almost frightening — the 17-foot giant dominates the National Park Service space on the western bank of the Potomac River.

If not for the “Welcome to Theodore Roosevelt Island” sign, one might assume the black stone colossus towering above the cement-slab plaza — his right hand raised as if to acknowledge the homage of marauding troops — was some sort of warring commissar.

Yet spiraling out from the fearsome statue are 88 forested acres of majestic trees and woodland paths designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., paying tribute to the conservationist and naturalist who was the 26th president of the United States.

“T.R.,” or “Col. Roosevelt,” as he preferred, could not abide being called “Teddy.” According to one of his biographers, he believed that “physical bravery was the highest virtue and war the ultimate test of bravery.” All historians emphasize Roosevelt’s “warrior persona” and his “speak softly and carry a big stick” ideology. As president, he destroyed the portrait of himself by Théobald Chartran because he felt it made him look weak, like a “meek kitten.”

Declaring himself “as fit as a bull moose,” T.R. gloried in fighting wars and shooting and killing wildlife. He donated several specimens bagged on hunting trips, including a snowy owl, to the American Museum of Natural History, which his father helped establish in 1869.

In fact, it’s hard to think of a more testosterone-charged president than Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), the “Rough Rider” who championed the “bully pulpit,” launched construction of the Panama Canal and brokered the end of the Russo-Japanese War, for which he won the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize, the first American to be so honored.

More than three dozen Roosevelt biographies are in print, including his own memoir — one of the 47 books he wrote, including “The Rough Riders,” “The Strenuous Life,” “African Game Trails” and “Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children.”

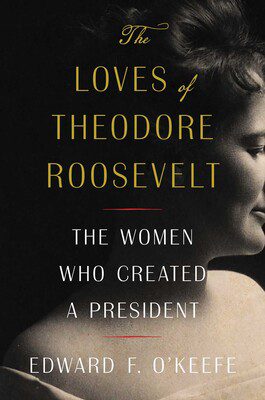

Now comes another biography: “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt: The Women Who Created a President,” by Edward F. O’Keefe, CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation, the group spearheading the building of T.R.’s library, currently under construction in the Badlands of North Dakota.

O’Keefe’s first book, “The Loves of Theodore Roosevelt” presents an astonishing thesis about the man whose rugged visage is carved on Mount Rushmore and who may be regarded as the exemplar of the XY chromosome. This biography proffers that “the most masculine president in the American memory was, in fact, the product of largely unsung and certainly extraordinary women.”

The author argues that five women provided the ballast of Roosevelt’s life and were the source of his greatest accomplishments: his mother, Mittie; his sisters, Bamie and Conie; and his two wives, Alice and Edith. Alice died in 1884, two days after their daughter, also Alice, was born. He had five more children — four sons and a second daughter — after marrying Edith in 1886.

These women were “the team who would guide his future for the next several decades and craft his legacy.” Indeed, O’Keefe writes, the two greatest mistakes T.R. made were when he acted on his own without the counsel of his female consortium.

“The biggest blunder of his political life was a pledge he would not seek what he called a ‘third’ term” as president. As vice president to William McKinley, T.R. assumed the presidency in 1901 when McKinley was assassinated and, in 1904, won election on his own. Then, without consulting his closest confidantes — Edith and his sisters — the newly elected president announced that he would not seek reelection at the end of his first term, a decision he sorely regretted.

Roosevelt’s second blunder, again made without consulting his wife and sisters, was to announce William Howard Taft as his successor. Later, T.R. became so distressed by his lack of judgment that he founded the Progressive Party, popularly known as the Bull Moose Party, and ran, unsuccessfully, on a third-party ticket against Taft.

In researching Roosevelt’s life at Sagamore Hill National Historic Site in Oyster Bay, New York, O’Keefe discovered something that had eluded previous biographers. A small, blue velvet box with a silk-covered divider contained a secret keepsake: a photograph of T.R.’s first wife and 14 inches of her wavy, dark, golden blond hair. On top of it was a note in Roosevelt’s own hand, reading: “The hair of my sweet wife, Alice, cut after death.”

Roosevelt has been described as an opportunist, exhibitionist and imperialist. But O’Keefe presents a perceptive and persuasive argument that adds a sensitive dimension to the masculine persona of Theodore Roosevelt as a man indebted to the women in his life, proving, as 19th-century poet William Ross Wallace wrote: “The hand that rocks the cradle is the hand that rules the world.”