When you’re with Elvis, you start to feel like a rock star.

When the “Elvis at 21, Photography by Alfred Wertheimer” traveling exhibition—an unusual collaboration among the Smithsonian Institution’s Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES), the National Portrait Gallery and Georgetown’s Govinda Gallery—opened at the NPG a while back, people involved in the show started putting off R&R vibes.

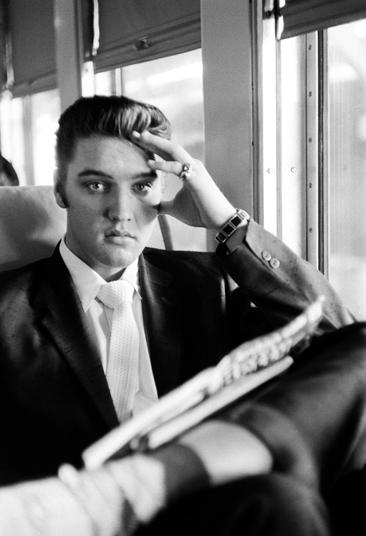

That seemed pretty true of Wertheimer himself. It’s been 54 years since he spent time with a budding national phenomenon named Elvis Presley, Elvis the pelvis, going to New York for an appearance on the Steve Allen show, to Richmond, Virginia, on a train ride to Memphis and Elvis’ pre-Graceland home.

If there was a star in addition to Elvis on the wall that day, it was probably Wertheimer himself, standing in the spotlight in a pretty cool gray suit, salt and pepper beard and hair, full of stories about what happened in 1956.

Right behind him stood Chris Murray, the founder of the Govinda Gallery, the man who had rediscovered Wertheimer’s cache of 1956 photos and shown them first in a small exhibition at Govinda a number of years ago, then added an expanded show eight years ago. Murray, who always looks like something of a rocker, is probably the king of rock and roll photography exhibitions in the area.

Even museum folks like NPG director Martin Sullivan and the exhibition co-curators Amy Henderson and Warren Perry, an Elvis buff who walked to school in Memphis on Elvis Presley Boulevard, had that Elvis buzz, along with folks with SITES, and the first visitors to the show.

Elvis had a way about him, and a little matter like his early death wouldn’t change that.

“I was lucky,” Wertheimer tells everybody about how he came to take the pictures that caught, in the most natural, raw manner, a down-home former truck driver just about ready to shoot out into the super-firmament, straddling home, the past, family, friends and old girlfriends, the fire already lit under him to propel him away from all that into legend. In these 40-some enlarged photographs, Elvis is caught smelling the jet fuel that was burning in him, and savoring the first taste of what it all might bring, while simultaneously loosening his grip on the ties that bind. He was changing right before their eyes, and in the process he was changing the whole damn country, (and scaring it a little).

“To be honest, I didn’t know who he was,” Wertheimer said. “But I got an inkling, that’s for sure. That was a special time.

It was 1956, almost right in the middle of the fabled fifties of normalcy, Beaver, the Hit Parade, fallout shelters, cars with big fish fins, Davy Crockett, sexual ignorance. We all loved Ike, even if we were Democrats. And Elvis was singing “Hound Dog” and shaking his tail like a demon. He was singing “Shake, Rattle and Roll”, and “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Blue Suede Shoes.” In February of that year, he had a Number One pop hit which nobody remembers now, the catchy “I Forgot to Remember to Forget.”

He scared people, mostly parents, television censors and people like Steve Allen, who got him to sing with a hound dog on his show.

What Wertheimer catches in these photographs is the beginning of a transformation—a boy singing roots music, still sometimes from a flatbed truck, changing into a star who could move his hips, show a pouty lip, hit the high notes and the low, and make girls scream en masse.

He was completely natural then, a little full of himself, sure of his way with girls, cool with the guys, relaxed. “I had access,” Wertheimer said. “The old fly on the wall thing.”

He must have been the most invisible little fly with a big camera when he caught Elvis with a pretty, blushed but cautious girl in a hallway prior to going on stage to sing. “He was trying to kiss her, you know, and she was doing what girls do, a little yes, a little no,” he said. “I had to shoot from up a little or behind and it was like I wasn’t there.”

It was kind of a seduction, a full-speed courtship, a kinetic moment, forever in the annals now.

Wertheimer had an eye for the periphery, a gift that actually allowed him to catch what was important. There are two shots of a girl who has just gotten an autograph from Elvis in New York; a sweet young girl who looks like she’s just about to faint, explode or burst into tears, or all three at once.

He caught Elvis on the piano in a hall, practicing, working a tune, and it was the kind of casual shot that might not look like anything, but it explains musicians, the secrets they keep. It became the cover for Peter Guarelnik’s classic biography “Last Train from Memphis.”

He also captured the country: Elvis at lunch counters in the south, where segregation ruled. Yet it was Elvis—by being the white kid who could sing so-called race music, mixing it with pop and gospel and country—who made it possible for people like Fats Domino and Chuck Berry to rise further into the daylight, escape the prison of category and burst into rock and roll. If there had been no Elvis, no Chuck and Fats and Little Richard, does anyone really think Bill Haley could have sustained the genre?

“I just followed him around,” Wertheimer said. “I don’t think I knew myself how important he would be. It was a freelance gig for a record company.”

Elvis was on the verge. In the last series of photos, which Wertheimer shot from the train going home to Memphis, Elvis dropped off, running home to his old neighborhood, parents, new swimming pool, running into the fields with only a piece of luggage, waving at the folks in the train.

Looking back, you might be tempted to think he was waving goodbye to his old life. If he was, we didn’t know and he probably didn’t either.