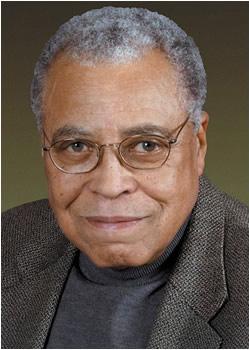

Kahn’s Classics: A Conversation With James Earl Jones

By • January 23, 2012 0 848

When the folks at the Shakespeare Theatre Company in Washington decided to add to its celebration of the company’s 25th anniversary by including a series of conversations between its artistic director Michael Kahn and celebrated (and classically trained) actors, they may not have guessed what a rich gift they’ve presented to Washington theater buffs.

But a gift the series is — and for free, no less — and has so far included dense, entertaining, enlightening theater talk between Kahn and a Starfleet captain, the star of “A Fish Called Wanda,” and, most recently, one of the Bingo Long Traveling All Stars.

Okay, truth be told, Patrick Stewart, Kevin Kline and James Earl Jones managed to come up with memorable theatrical performances before (and after) they ever appeared in a motion picture, including notable roles in the plays of William Shakespeare.

If the series—we hope it will be permanent—was intended to be grounded in discussions about the craft, education and performance of classical theater, they quickly became much more than that, because of Kahn, with his own long history as a director in the theater, with his puckish, sly sense of humor and gift for story-telling and sharing.

While there was always talk about the how of acting and theater, about process and methodology, it’s never sounded like that. Rather, it sounded like two theater friends, talking about stuff over a glass of water in front of a few hundred people, as it were, as if in a play, or many plays. Kahn and the three actors so far—all of them stage actors who had found almost pop culture fame in movies and/or television—were swapping fascinating, almost insider stories around a campfire, but they were also familiar tales, familiar to us because we had encountered their art, their gifts somewhere, in a theater like this, in a movie theater or at home on television. If we were here in attendance, then these men had been, at some time or another, a part of our lives, sometimes a large part.

Certainly, that’s true of James Earl Jones, a large man with large gifts, who made his way to the stage slowly, but in very cool fashion. Jones is just over 80 years of age, but going strong, working the stage a lot now—back to Big Daddy, to “Driving Miss Daisy” and prepping for a new production of Gore Vidal’s vital-still American politics play, “The Best Man.”

We know Jones, of course, from “The Great White Hope,” which first found life in this area at Arena Stage back in the 1960s, a revolutionary, long, dynamic and outsized play about the controversial fighter Jack Johnson who became the first African-American boxer to win the heavyweight title, incensing the predominantly white boxing world, and then, taking it one step further by having a white wife. Jones owned that passionate, taxing part lock stock and barrel and also starred in the film version with Jane Alexander.

“People always say that nobody could really play that part but you,” Kahn said. “Well, that’s not true, but I know I’m associated with it, that it’s mine. But Yaphet Katto (who also shared “Fences” with him), and Brock Peters did great with that part. But it changed my life, it gave me a certain amount of fame and standing, that’s for sure.”

Kahn asked him, as it is with many actors who have done film and stage work, the difference between the two. “Well, different aspects of your craft are emphasized and required,” he said. “But it’s different for everyone. I was told by the film director of “Great White Hope” not to overact the part, that things would be done in the editing room. I didn’t yet know what I was doing and I can’t say I did a perfect job. I think Jane (Alexander) struck the right balance.”

Jones’s fame and familiarity are historical—with his size he opened big doors and other African-American actors walked right through it. “Of course, you’re aware of who you are, the social aspects, the injustices, the disparities, your own history. But you cannot be bitter, you cannot just blame, or you will never succeed. I tell young black actors everything they will encounter, what’s unfair, the parts they won’t get. But you know, it’s a hard profession, period. It’s hard for young white actors, too.”

Jones was a stutterer, a fact about him that isn’t always commonly talked about. “I had help and good advice. I find that on the stage I don’t stutter, because the language, the spoken word is so strong, so musical, almost, it’s like singing, when you’re passionate, you can speak clearly.”

When it comes to films, he had a nice little start: his first movie role was as the bomber who couldn’t get the bomb loose in Stanley Kubrick’s “Doctor Strangelove.” “What a great film, I was lucky with that. So, Slim Pickens had to ride the bomb down to Moscow.” This was in the 1960s when his peers where people like George C. Scott, Richard Harris and Richard Burton among others.

Jones had the part the common soldier who gets into an argument with King Henry in “Henry V,” about how war is different for the king and the soldiers, not knowing he’s talking to the king, in a Joseph Papp-directed version of the play. “This was the ’60s, you remember, and everyone thought he was somehow making an anti-war statement by casting me,” Jones said. “He wasn’t, as far as I know. I was a spear carrier.”

He became much more than that. Especially when he encountered “Othello.” “My god, I have played Othello seven times,” he said. “I still don’t think I got it right. I don’t know. Different Iagos, different Desdemonas. I sometimes I think when I played it with Christopher Plummer, I sometimes think I should have grabbed Iago and stuck his head and near-drowned him in a fountain when I said, ‘Prove my wife a whore,’ to add emphasis.”

He was asked if he thought Iago, the man who plotted against him and made him believe his wife had betrayed him, was a racist.

Jones took his time answering. “On balance, I do think so,” he said. “It’s not good enough, as some people suggest just to say he’s naturally evil, like Richard III. He mesmerizes people, including Othello. But he has an advantage. He talks to the audience. Othello doesn’t.” This led to discussions about Shakespeare’s intentions and feelings vis-a-vis race and prejudice, a controversy that also simmers every time out over “The Merchant of Venice,” and its central character of the Jewish moneylender Shylock.

It’s something we all forget sometimes. In the life of these men, they have played many parts, and we remember their bearing, their voices—especially the resonant, powerful voice of Jones. They are in our minds and dreams and the way we remember them mostly is: Stewart making the U.S.S. Enterprise go to warp, the voice of Darth Vader, in movie images. The tales of the stage are just that: memories.

I happened to see Jones and Plummer in “Othello,” which happened to include an over-the-top performance by a pre-“Frazier, “pre-“Boss” Kelsey Grammer. And you realize then that while those of us lucky enough to be able to see many plays, nevertheless, see them really only once. To Jones, there must be a thousand Othellos in his head, the voice modulated a little here, a line slipped there, the hand on Desdemona’s throat softer or stronger each night.

But, we remember too and being with them like this makes us think and remember. Later, going home from the talk in a cab, the Ethiopian cab driver talked heatedly about Othello, although he has only seen a film version, while I remembered Plummer and other Iagos, saying “I hate the Moor.”

These classical conversations have been classics. Bravo.