The Last Baseball Story: Until Next Year, Nationals, Orioles

By • October 23, 2014 0 874

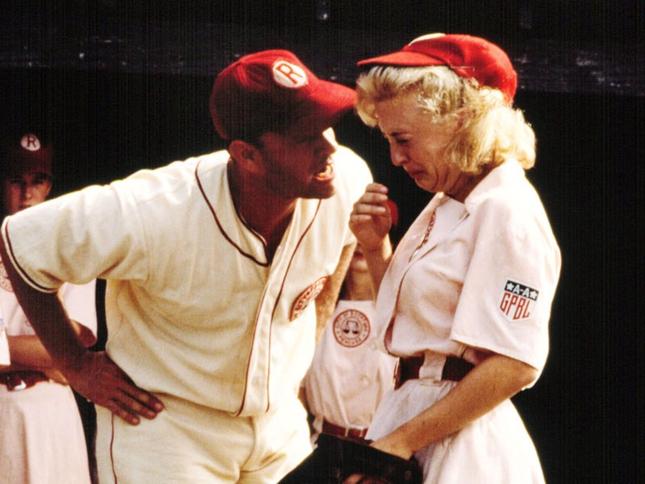

Remember “A League of Their Own,” the 1992 Penny Marshall-directed movie about an all-girls baseball league during World War II? At one point, Tom Hanks, playing the gruff old-pro manager of one of the teams, the Peaches, watched exasperated as one of his players burst into tears after he had chewed her out at length for making an error.

Shocked, he turned to her and yelled: “You’re crying? You’re crying? There’s no crying in baseball!”

Guess again.

There’s a hell of a lot of crying in baseball going on right now, right here in Washington, D.C., and up the road a piece in Baltimore, and all of Southern California and probably in Mudville, too.

The Washington National, owners of the very best record in the National League for the second time in two years, lost three excruciating, nightmare-inducing, heart-breaking games to the San Francisco Giants, an NL wild-card team, same as they did two years ago, against the St. Louis Cardinals.

Not only that, but the California Angels, owners of the best record in the American League and all of baseball, were swept unceremoniously by the Kansas City As, a—you guessed it—a wild card team who hadn’t won much of anything in decades.

The very same A’s, as of this writing, own a 2-0 lead over the Baltimore Orioles, the Nats’ nearby rivals, in a best of seven American League championship series.

Wait. There’s more. The Los Angeles Dodgers, owners of the second best record in the National League and the highest payroll in the land were dumped by the St. Louis Cardinals along with Clayton Kershaw, without argument probably the best pitcher in baseball. At this writing, the Cardinals and Giants are tied 1-1 in the NL Championship series. It’s entirely possible that two wild card teams will play in the World Series.

But, then, that’s baseball. The history of baseball is full of ghosts—of inches and feet, of seconds. It is measured as much in improbabilities as in certainties.

It’s a tale of opportunities lost, and glorious triumphs, of heroes who come through in the clutch, of impossible catches, and blown saves, of blunders and homers and boners, of improbable losses and improbable wins, of heroes who fail and little known players who become for one moment heroes.

Nothing bears this out than the Nationals-Giants four-game set, won by the Giants, 3-1. Here at the most important stats—forget all these new numerics baseball geeks have come up. 3-2, 2-1, 3-2. Three. Those were the scores of the games the Nationals lost, two at home and one to end it all in San Francisco. In there was a last hope-inducing 4-1 victory by the Nats in SF. The margin of error was about the length and size of a breath held a little too long.

The Nats squandered an efficient, if not brilliant, pitching performance by Stephen Strasburg in the opener, plus a couple of home runs, one from Harper. Then, they entered into what would turn out to be the longest game ever in playoff history, 18 innings or the equivalent of two games, and lost, 2-1, just after the clock struck midnight.

The game stretched heartache every which way. With Jordan Zimmerman, who had pitched a no-hitter in his last outing, cruising in the ninth inning with a tingly 1-0 lead, he walked a batter, prompting a prompt thumbs out from Manager Matt Williams, who replaced Zimmerman with Drew Storen, who had been doing well in his year of redemption, the same Storen,who blew the decisive game in the playoffs two years before. He allowed the hits that produced the tying run the seemingly endless deadlock broken up by a San Francisco home.

The 2-1 loss highlighted almost everything baseball is about, including its endless open-endedness. A manager appeared to forget that the game is about the players and the fans—not the managers. As has been noted, the game should have been Zimmerman’s to win or lose. He’d pitched a phenomenal 17 straight scoreless innings.

You can’t blame the manager, who also got thrown out of the game the next inning, for everything. In a short series, a slightly inferior team can beat the favorite if that team suddenly stops hitting altogether, which the Nats did, pretty much up and down the lineup except for Harper and Rendon. At one point, they went 21 innings without scoring until the seventh inning of the third game.

Baseball is a game full of Sunday sermon homilies of hope, which springs eternal everywhere, but especially in baseball. Baseball, unlike other sports, has no clock. So, as the saying goes, it ain’t over ’til it’s over, which is to say until after the last out.

Anything can happen goes the siren song of hope, and the Nats, needing to win three straight, won one, bringing that emotional pinch hitter hope out of the dugout on wobbly legs.

It had been done before. In 2004, the Boston Red Sex, down three games against the Yankees in a seven-game playoffs, won four straight, to take the AL title, and then swept the St. Louis Cardinals 4-0 to win the Series, reeling off eight straight wins.

Hope springs, partly because the sport is full of ghosts and memories, and its literature is rooted in the hieroglyphics of the box score.

In some ways, it’s a game of stillness, interrupted by furious seconds of actions—the crack of the bat, the missed swing, the slide and throw at home plate, the loud rocket noise made by thunderous home runs, the swift blur of a double play, (Tinkers-to-Evers-to-Chance) and the basic rhythm of pitch, swing, hit (or not), catch (or not), and run. Towards home, always the journey towards home.

Nothing is certain in baseball—it is a battle against obvious futility, in which a player is deemed to be an excellent hitter by making outs two out of three times. It is a game that leaves players naked—you can’t always spot the grievous missed block in football, but when a hitter strikes out with the bases loaded, he might as well drop his pants.

Baseball is full of ghosts—the ghost riders in the sky of the heroes and triumphs of long gone players, and their mistakes and blunders and failures under pressure. In the 1964 World Series between the New York Yankees and the St. Louis Cardinals, Cards manager Johnny Keane allowed the brilliant but struggling Bob Gibson—one of the most fearsome pitchers ever—to finish the game, grimly winning a 7-5 game. “I was committed to this fellow’s heart,” Keane said. The vagaries of baseball and its glories were on display that fall—Mickey Mantle in his last year of playing for the Yankees, hit three home runs in the World Series, manager and Yankee legend Yogi Berra (“When you come to a fork in the road, take it”) was fired. Johnny Keane became the Yankee manager, and he too would eventually be fired.

This time of the year, fall with leaves and nuts on the ground, and in the stands, is baseball season when all the other things—steroids, unbelievable salaries, and so on—just fade away.

We are seduced by baseball’s long-treasured cliches, listening for the opening words as if in a play in a theatre: “Play ball!” It is the baseball equivalent of “Places, please.”

We hope until hope is gone as it was in Mudville and as it is in Washington. So, we embrace another old slogan, hope’s last ditch siren song: “Wait until next year.”