On MLK’s Birthday, We Celebrate His Life, Words

By • January 28, 2016 0 808

This Monday, this city, this country will be celebrating the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who would have been 86 years old Jan. 15, had not an assassin’s bullet ended his life at the age of 39 in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4 in that tragic, momentous year of 1968.

One of the highlights of the day, besides the Martin Luther King, Jr., parade is Georgetown University’s annual celebration of King’s life at the Kennedy Center. Click here for details on the free 6 p.m. event on Monday. Click here to see the week’s events dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr., at Georgetown University—and beyond.

King moved through his life, compelled and propelled to be the leader of a movement for justice, for peace, for righteousness—the vanguard leader of the Civil Rights Movement, seeking justice and rights apportioned to all Americans for African Americans. When the times were changing, he and his compatriots in leadership changed the culture and face of America.

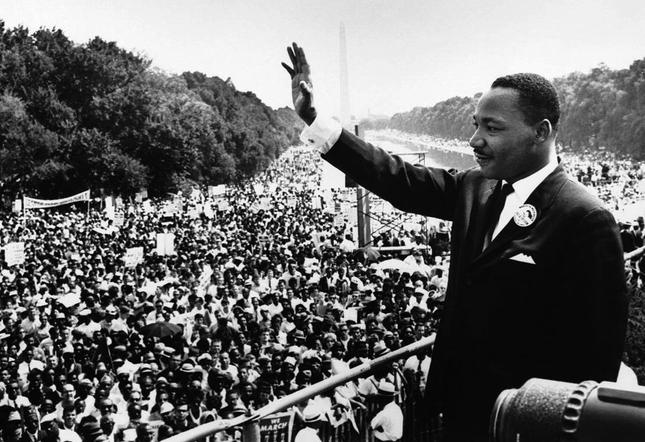

It was an evolutionary process as he and the country changed. It was a sometimes violent, dangerous struggle, with casualties, chief among them King himself. He moved from schools to lunch counters, to the back-to-the-front-of-the bus and from the 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, to the Nobel Peace Prize—and, finally, to “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech, hours before he died.

He and we, and all of us evolved, and we celebrate his birthday, only days after Barack Obama, the country’s first African American President—a fact that speaks volumes of books that are still not closed—gave his last State of the Union address. In it, he called for an end to obstructions placed in the paths of some voters.

Civil rights and their achievement and interpretations are ongoing, still moving forward, still sometimes sliding backwards, still sometimes extended to more and more groups and people who have been thus denied.

After the United State of America was born in the forge of an idea that “all men are created equal,” we then fought a bloody civil war to achieve it fully by ending slavery, if not racism, and then took another century to achieve in actuality by ending Jim Crow. The nation still bleeds at times from the wounds of its past.

There is little point in wondering if King would be at the forefront, marching with the folks proclaiming that “Black Lives Matter”, and that he would be encouraged by the demonstrations against perceived and less obvious forms of racism on the nation’s campuses. He would; we can say that with certainty. He might give cogent, inspiring answers to the folks—the Trump followers railing against political correctness, the immigrant and the “other.”

History has a way of changing itself and how we view it. It makes us see some things as new, the old as an affront to the now and new, the past as informing the present—and vice versa. That is part of King’s legacy, part of the man whose life we celebrate. The achievements hitched to the rhetoric and the life are permanent, the life human, full of struggle, doubts and expressions of courage and vision, the words stirring us to action still.

A monument to the life, the man and his words and achievements now graces the National Mall in Washington, D.C. People by the thousands remain drawn to it and will no doubt show up Monday to give due honor and reflect—or perhaps to join hands and sing the old songs of the movement, bringing the statue to life.

In our mind’s eye, flickering images remain. The spirit does not die, and many people—thousands and through time millions—still have a dream: his and ours.