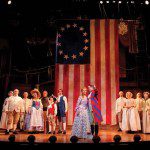

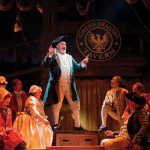

Liberty Smith at Ford’s Theater

By • July 26, 2011 0 1865

You’d think that a new musical set during the Revolutionary War featuring a hero that’s somewhere between Forrest Gump and Zelig might be something of a risky undertaking for the Ford’s Theatre company.

Ford’s executive artistic director Paul Tetreault doesn’t think so. Not even a little. “I think it’s a terrific show. I love the whole idea, and I think it’s perfect for us,” said Tetreault, who took over in 2004 after the death of founder Frankie Hewitt.

When Tetreault, who came to Ford’s from the famed Alley Theater in Houston, talks, you tend to listen. So chances are that “Liberty Smith,” maybe Ford’s biggest musical undertaking ever, may just be the audience-pleaser that Tetreault thinks it will be. He’s been right before.

The Revolutionary War as source for theater entertainment is historically a mixed bag. The pinnacle of the genre is surely “1776,” a musical about the haggling founding fathers as they try to come up with the Declaration of Independence, which proved to be a mighty Broadway hit, and continues to be a hit in revivals all over the country (including one at the Ford’s earlier this decade).

“Liberty Smith,” a kind of tongue-in-cheek, young-hero retelling of some major events of the revolution, has a few things going on for it. It has a top-notch, experienced creative team with a book by Marc Madnick and Eric Cohen, music by Michael Weiner, and lyrics by Adam Abraham. Weiner is a veteran of Disney musicals and films and wrote the music for “Second Hand Lions,” which is slated for a New York opening at the end of the year.

“We think this is going to be great entertainment,” Tetreault said. “With the involvement of people like Marc, Eric, Michael and Adam, we have a big, Broadway-style musical here, which will appeal to the whole family.”

“Liberty Smith” features a cast of 20, including a number of musical comedy veterans like Donna Migliaccio as Betsy Ross. Using local stars has been a Tetreault trademark—witness this year’s production of Horton Foote’s “The Carpetbagger’s Children,” which starred Holly Twyford, Nancy Robinette and Kimberly Shraf. But the main attraction and the key to the production will be Geoff Packard, the critically acclaimed and appealing star of the recent production of “Candide” (under director Mary Zimmerman) at the Shakespeare Theatre Company.

Smith appears to be the kind of characteristically American tall-tale character that somehow did not get mentioned alongside Davy Crockett, Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill and Johnny Appleseed. Yet there he is, boyhood friend of “George” (Washington), apprentice to Benjamin Franklin, trying to get Thomas Jefferson to quit fiddling and write. He helps out Paul Revere on a horse and steers Betsy Ross with her knitting while courting her niece, the pretty lass who’s mad that she can’t do what the founding fathers do because she’s a woman.

“We’ve been working on this for a couple of years now,” Tetreault says. “We’ve taken great care to get it right because I think it’s a very special project.”

Tetreault stepped into the shoes of several legends when he arrived at Ford’s. There was Hewitt, who founded the renewed theater as a functioning performing entity and faced the same challenges that Tetreault did: the theater is a historic structure, and a gloomy one at that. It is where another legend, Abraham Lincoln, was murdered while attending a comedy. And there’s no getting around that. This is theater as museum, a tricky kind of thing to provide programming for.

Lest you forget, there’s always the flag-draped presidential box to remind you.

Hewitt trod a careful line—musicals were always a strong fare, many of them exceptional (think of the originally produced “Elmer Gantry”), most of them entertaining for the tourist trade. And that’s the economic trick, of course—the Ford’s is as close to a historic national theater as we have, which both guarantees tourist audiences, and makes original programming and theatrical respectability difficult to get.

Tetreault realizes, as did Hewitt, that you probably can’t do “Streamers” here, or Mamet or “Sylvia,” and so critics tend to often arrive in the early years with a built-in, genetic sneer, which was often patently unfair.

Hewitt presented classic, historical fare, but also many African American plays and musicals by and about African Americans, something that local audience were starved for.

Tetreault has often surprised people with his choices, but more often than by the critical and popular success of those choices. Sometimes, when you look at a Ford’s season schedule, the nose can turns up by itself, which just goes to show you that you can’t trust your nose any more—at least not in the theater.

One of his first successes was the staging, with the National Theater for the Deaf, of “Big River,” a redo of the musical version of Huckleberry Finn driven by Roger Miller’s easy-going music. This production, while delivering the entertainment goods, discovered surprising depths to the show in the performance.

“I think I have a lot of leeway in what we do,” Tetreault says. “You can find originality, emotional depth, and theatrical excitement in American theater stories. I believe in partnering, because that’s the future of theater. It’s the here and now.”

By partnering with the African Continuum Theatre, Tetreault steered a highly praised (and unlikely) production of “Jitney” to Ford’s stage, which resonated mightily. A partnership with Signature, under director Eric Schaeffer, resulted in one of the best musicals ever produced ground-up in Washington, the exciting “Meet John Doe,” based on Frank Capra’s stirring populist movies.

After exciting remodeling—which took out two full seasons—Ford’s re-opened looking much better, but still very much a part of the greater Lincoln atmosphere getting built in the surrounding area. The theater opened without missing a beat, coming up with four straight hits: “The Heavens Are Hung in Black,” a new commissioned play about Lincoln’s time in Washington, “The Rivalry,” about the Lincoln-Douglas battles, “The Civil War,” and (just for fun, I suppose) “The Little Shop of Horrors.”

But who would have thought that the 2010-2011 season debut “Sabrina Fair,” a 1950s romantic comedy about a chauffeur’s daughter who has to choose between two wealthy brothers, would look so fresh with new faces and a different, youthful outlook?

Paul Tetreault did.

So “Liberty Smith” may be a gamble, but it’s probably a good bet.

- Liberty Smith, at Ford’s Theatre | courtesy of Ford’s Theatre