Could Banking’s Past Become Its Future?

By • December 5, 2014 0 1630

Whenever I pass the intersection of Wisconsin Avenue and M Street, I am reminded of my father, a banker in my hometown for 35 years. Anyone who visits Georgetown knows the beautiful, gold-domed building with a marble facade that, once upon a time, was home to a local institution, Farmers and Mechanics National Bank, later a branch of Riggs Bank, and today a branch of PNC, as evidenced by the sign bolted over the door.

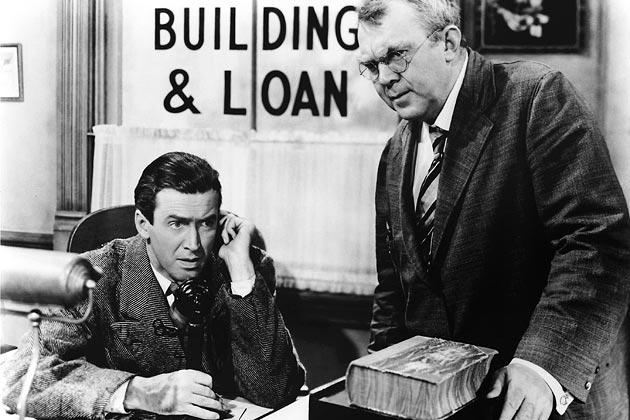

If (and when) PNC is taken over by an even larger bank, this will make it easier for the next owner to unscrew the old sign and attach a new one. It’s an apt metaphor for what we’ve learned during the past five or so years: you can’t bank on financial institutions that are too-big-to-fail and too-big-to-care. At first look, it would appear the local banks my father worked for are now a relic of the past, where bankers understood both banking and their customers—and where you went to the same church, supported the same charities, shopped at the same local stores, and your kids were on the same sports team.

My father’s experience—before the revolving door mergers began in the 1990s—was that the core profit for his bank depended on the community’s trust.

During the 1960s, like many cities across the country, our community was devastated by riots. But what I remember the most was how my father walked down the street to all his local customers, whose businesses had been damaged, and offered them on-the-spot loans to rebuild. He likes to say that every loan was repaid and those customers remained loyal—until the bank was taken over by a bigger bank and my father was forced into retirement.

Today in developing economies micro financing is thriving not because the customers are tycoons but because they know their customers. I’m not condemning growth and change, but for far too many global public banks it has become a faceless game of risk-reward, where underwriting is simply a FICO score.

While the bank my father worked for is history, I see signs of hope for the type of banking he practiced. Looking in our own neighborhood, you can see local institutions that operate on principles like those of one of the District’s most notable bankers, Robert P. Pincus, vice chairman of EagleBank. His success is rooted in his passion for giving back to the community and his personal policy includes buying suits from a local tailor and dining at locally-owned restaurants, instead of chains.

Other community banks include Bank of Georgetown and Cardinal Bank, which provide services to small businesses including construction loans and contribute to local charities. They are known in the community, and they know us, too.

Today, buying produce from a local farm, meat from a local butcher and carrying it home in an eco-friendly reusable bag is considered “trendy.” So, why don’t we consider banking local?

It might be worth examining the institutions we give our business to, and whether our bank is supporting our community. The definition of capitalism is increasing cooperation between strangers. Maybe it’s how we define “stranger” that is really the threat of “too-big-to-fail.”

*John E. Girouard, CFP, ChFC, CLU, CFS, is the author of “Take Back Your Money” and “The Ten Truths of Wealth Creation.” He is a registered principal of Cambridge Investment Research and an Investment Advisor Representative of Capital Investment Advisors, in Bethesda, Md.*