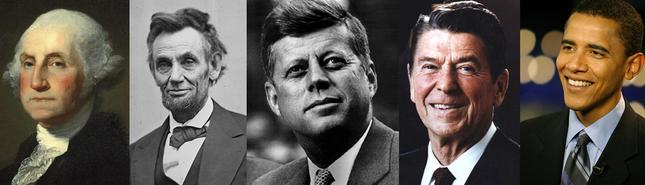

This is the time of year when Americans think about presidents—two of them, specifically—and make a holiday out of it. We call it President’s Day.

Usually, it’s about George Washington, the first president, and Abraham Lincoln, the most haunting, memorable president.

This year, it’s worthwhile to think a little broader, farther and wider. Things are happening. For instance, we’ve been thinking a lot about Ronald Reagan on the occasion of the centennial of his birth. The remnants of his family, friends and associates, their memories and stories still fresh, have been talking and writing.

It’s also been the 60th anniversary of the inauguration of John F. Kennedy, and again, memories and meaning were on the airwaves and in the newspapers. Celebrations were held at the Kennedy Center and the National Archives where Caroline Kennedy, JFK’s surviving child, presided over music and introduced the digitalization of the JFK library.

In this country, presidents are ever on our minds, including and especially the current one: President Barack Obama, the 44th President of the United States, and the first African American President of the United States.

It’s worth thinking about how we feel and think about our presidents—all of them— although its fair to say we hardly think of many of them at all; and that includes both ends of Tippecanoe and Tyler too and the middling to obscure presidents of the 19th century. When is the last time you’ve had a chance to use Chester Arthur in a conversation, or sung the praises of Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchanan, who, when it came to slavery, was like Scarlett O’Hara? We’ll worry about it tomorrow (meaning, he passed it on to Lincoln).

So, who do we think about? The exultant, vocal members of the Tea Party think and talk a lot about the Founding Fathers—sometimes as if they could read their minds and were on intimate terms with them. In knowing Washington (who just had a 900-plus page biography written about him), John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, I defer to the Tea Partyists. I know one thing about them, and that is that not a’ one of them dreamt, thought, or talked about becoming President of the United States, which is now a cherished dream and opportunity among the entire American citizenry instilled from birth. “Some day, you too, can become President.”

When our first batch of presidents was young and childlike, there were in fact no presidents. There was no United States of America. There were only kings, emperors, a few prime ministers, empresses, shoguns, Pashas and fact totems and powers behind the throne, and scattered parliaments here and there.

The president is an invention—our invention. The Head of State as a man (or woman today) of the people, representative of and obligated to the people, doing the people’s work at their sufferance.

But make no mistake about it: when someone becomes president, he becomes someone else, he becomes history, fable, legend, sun king. To regular folks, he becomes myth and savior, priest and devil all rolled into one. Listen to the talk about Kennedy and Reagan these days. They have moved beyond their own history, achievements and failures, into something much larger.

This town is full of statues, of course. Memorials, metaphors and mulch. A bust of JFK sits, wounded-like on the red carpet of the Kennedy Center, which seems appropriate. Reagan’s memorial is a multi-purpose building housing offices, think tanks and every which kind of function. We have the spear of the Washington monument, the rotunda that is the Jefferson, and the Lincoln Memorial.

It’s interesting who we remember and how. There’s a certain commonality among the men we remember most: they seem, and are often remembered as, unknowable. Reagan’s family members and associates, while extolling his chief virtue, which was communicating a boundless American optimism, also remembered a distance within him.

JFK’s chief vices were personal, but what’s remembered was an ability to inspire people with rhetoric and vision. One of his biographies was titled “Johnny, We Hardly Knew Ye.” And that’s probably true.

Bill Clinton is well remembered today because of his unquenchable thirst for experience and love of the people, a quality that persists as he remains among us. It’s interesting that George W. Bush, whose presence at the recent Super Bowl was hardly noted, has written an autobiography, perhaps prematurely.

We don’t know them. They become changed people. We see their hair change color, and we watch them in crisis, publicly, every day, at press conferences, waving to crowds, collapsing into the presidential bubble that even a visit from Bill O’Reilly can’t dent. I don’t think any of us have ever seen a man endure such a public embarrassment as Bill Clinton did during his impeachment trial, and yet he overcame that bit of history almost in triumph. Richard Nixon, the only man to ever resign the presidency, somehow came back to achieve a distant stature as a member in good standing of the Wall Street legal establishment, and a painful puzzle in history.

The presidency, you have to think, is a kind of trial by fire for an individual, and a good part of it is beyond the President’s control. Think about Obama for a moment: in the wake of his State of the Union message, he appeared buoyant, on the rise in the eyes of the people. Then Tunisia and Cairo happened and has engulfed his attention with results that remain to be seen.

Many of us will have actual memories of several presidents, living and not. It was, for me startling to see a video clip during the JFK library press event showing JFK and Eisenhower talking in the most casual way during the Cuban Missile Crisis, which seemed only like a possible nuclear Armageddon for most people who were alive then, including me.

Ike was my first president, and all the rest followed. But I find myself thinking often, not of them or the Founding Fathers, but of Lincoln. I suspect that’s true for many folks. We gather in his presence often, the place where we try to find succor, inspiration, hope. The place where we can be safely defiant and insurgent in our discontents.

I think Lincoln—also unknowable, but not unaffecting—lived the most intense presidential life in the space of four years that any one person could reasonably fold unto himself. I do not think there has been a man who has experienced more pain, more suffering, and, perversely, historic glory, than Lincoln. He seems a personal man who kept his own pains and memories secret, but took on other people’s sufferings because the moment—that great shattering civil war—demanded it. And it showed in his face, his choice of reading (Bible and Bard), his own words and writing, which were clean like an arrow to the heart.

He was, as Whitman wrote, our captain and remains so. He is the ghost in our history, it’s still restless soul. I think we see that on the Mall, at certain times in our history, in the coil of history’s movement.

He is not a Republican or Democrat, not a Methodist or a Jew, not a frontiersman or an urban legend. He is, for want of a better word, the President as hero. And you know what they say about nations and heroes…