Gods and Conservation: Paul Jett at the Freer/Sackler

By • July 26, 2011 0 2055

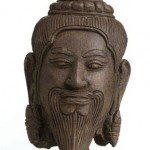

Walking down the long staircase and into the galleries of the Sackler, a large stucco Gandharan head of a Bodhisattva from Afghanistan sits on a pedestal above eye level. Sensuous and spiritual at once, its lips are full and it is crowned and has flowing hair. The spiritual dimension is evoked with the semi-closed eyes and the tension of the eyebrows, seemingly meditative. It is many times larger than human scale and must have stood on top of a very large body.

When Paul Jett, head of the Department of Conservation and Scientific Research of the Freer/Sackler, first saw the piece, it was covered with detritus of almost 2,000 years. Jett related to me, “Pieces you spend a long time working on you get more attached to. I feel very attached to the Bodhisattva. No one would display it because of the way it looked. I thought this piece had potential, so I spent eight months working on it, often through a microscope, as stucco is very delicate. Everyone liked it so much that now it is on permanent exhibition.”

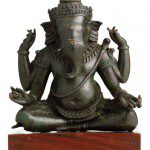

Adjacent to the Bodhisattva is an exhibition of Khmer art curated by Paul Jett and Louise Court, the highly regarded curator of ceramics at the Galleries. The exhibition will later go to the Getty in Los Angeles. The Khmer bronzes displayed are extraordinary in their energy and refinement. They have a certain formal reserve that is very apparent in Khmer stone sculpture, but due to the scale of the pieces they are more intimate. Paul Jett played a major role in this exhibition, mentoring the conservation staff at the Phnom Penh museum in Cambodia where these works are from.

As we walked through the exhibition, Paul Jett recalled his early career: “I grew up in New Mexico, where I pursued interests in photography, painting, and sculpture. I got a Bachelor of Fine Arts in New Mexico. I worked at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts doing a post-graduate fellowship and came to D.C. and got the job at the Freer/Sackler. I studied bronze casting at Glen Echo. When I started working at the Freer/Sackler, I realized that I had prepared for it by studying Mandarin, as well as Chinese philosophy and history.”

Working with Asian bronzes has involved Jett in precarious, technical studies with gold and silver. Asian bronzes often have silver as inlay or are coated in gold. The philosophy of conservation today, according to Jett, is “Do no harm to the object, make repairs unobtrusive, though not exactly invisible. And importantly, all repairs have to be able to be undone.” In looking at art in museums he says, “I do notice how it’s been restored, it’s hard to turn that part of me off.” He says of his work on pieces, “It will last for hundreds of years. We make decisions sometimes on our own or will consult with curators or directors depending on the piece.”

The work with the Phnom Penh Museum started in 2005, setting up the conservation lab. Most of the training took place in Phnom Penh. Jett says, “There was a blank slate for most of the students.” He says that this was an advantage, as he did not have to deprogram anyone. Jett became close to his colleagues and students who did most of the work on the pieces in the exhibition. “They are doing fine on their own,” he says.

One thing he did as a demonstration was to fill in a bit of the Nandi, a large 12th- to 13th-century bronze. It is discernibly not an Indian Nandi, yet having a similar languor. Many of the figures of the gods in the show are based on Indian prototypes, but have evolved into their own distinct Khmer-ness. The Ganesh has none of the earthiness found in his Indian prototype, even though it has a similar physique.

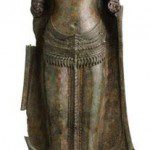

Being with Paul Jett at the Gods of Angkor show made me look harder at how the pieces were put together originally and through restoration. We stopped to admire an incredible bronze crowned Buddha from the 12th century. Holding up its arms in abhaya mudra it blesses this beautiful show.