Nam June Paik and Lewis Baltz at the NGA

By • July 26, 2011 0 1549

Nam June Paik and Lewis Baltz are not a likely association. They’re not Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, Picasso and Braque, John Cage and Merce Cunningham.

Born in Korea, Nam June Paik (1932-2006) was a contemporary, avant-garde composer who became the pioneer of video art. Lewis Baltz (b. 1945) is a fine art photographer who made a career out of capturing bleak industrial landscapes of parking lots, office buildings and empty storefronts. Paik worked in New York City, Baltz worked largely on the West Coast. The two artists never met in any substantial capacity or worked together, nor did they express any noted interest in one another.

What they do have in common is that their works are both on display in compelling, complimentary exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art. With these concurrent shows, the National Gallery has fostered a dialogue on the industrial and technological sprawl of the mid to late 20th century. Together the installations offer a look into the searching minds of modern artists dealing with the encroaching disaffection and homogeny of surrounding environments, cultures and medias. That these artists came to such similar conclusions in their work in such different ways is remarkable, but as the Gallery suggests, it is also perhaps inevitable. As art historian David Joselit said, “It’s hard not to ask oneself how something so simple has become so complex.”

Joselit was referencing Paik’s installation, now on view in the Tower Gallery in the East Wing of the museum. As with many references in modern art, this statement is at once glib, generalizing and grandly ubiquitous, while concurrently site-specific. The Paik installation is all of these things—which is not to say it isn’t great.

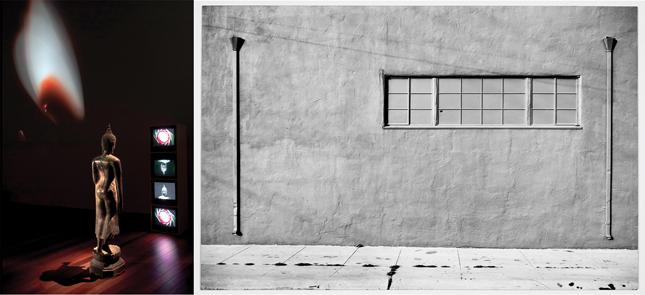

A lone candle burns in the middle of the totally dark room. Monitoring the wick with its infrequent flickering is a video camera, whose uncompromising gaze at a proximity of a few feet is—not unintentionally—hilarious. The camera is plugged into a jumble of wires, which the gallery leaves visible, connecting to a number of projectors that cast the candle across the room in a smattering of prismatic, Technicolor distortions and spliced RGB projections.

Off to the side a Buddha statue, defaced with paint and graffiti, stares at itself in a column of four stacked televisions, which display distorted images of the Buddha, which is in turn lit only by the light from the TVs that are reproducing its own image, and so on to infinity.

Indeed you ask yourself, standing in a room that is decidedly obsessed with itself and all its unsacred nothingness, how something so simple and pure as a candle is suddenly laid out in such nonsensical, overwrought terms. The Buddha, a symbol of holiness and enlightenment, becomes the center of its own limited universe. Something so virtuous turns unappealing, dirty and unwelcoming.

Much like the aluminum siding, cracked concrete walls, paint-flecked steel doors and potholed asphalt Baltz captured in his photographs. The great human striving for culture and community, beauty and betterment, is historically manifested in architecture. In this respect, Baltz’s portraits of deserted storefronts, alleyways, parking lots and gutter drains offer grim criticism of American taste and progress. Largely void of any perspective or horizons—and completely void of human life, natural elements and anything beautiful—these pictures draw attention to a loss of history, a cloying triumph of mass industrial corporation in the cultural landscape of our country.

Television, Paik’s medium of choice, is a part of this takeover. (Paik in fact made a point to note that he never actually watched TV, but used them only to distort or create images.) The artists together speak about a world in decline—not by way of bankruptcy, war or starvation, but by way of shriveling beliefs and restrained, unengaged consciousness.

However, maudlin sentiments aside, the shows also work very well as plain old art. Baltz’s photos are beautiful in an abstract way—many of his contemporaries were minimalists, and paintings by Richard Serra smartly accompany this exhibition. Baltz has a sharp, classical sense of composition, and his images induce a sort of hollow nostalgia. The Paik installation is in turn a lot of fun and eerily interactive. Stand behind the Buddha and you become part of the perpetual image; you are tempted to blow at the candle to watch the room bounce with light. Or perhaps you’re tempted to blow it out.

“In the Tower, Nam June Paik,” through October 2 in the Tower Gallery of the East Wing of the National Gallery. Lewis Baltz’s photography exhibition, “Prototypes/Ronde de Nuit,” through July 31 in the West Wing of the National Gallery. For more information visit NGA.gov/Exhibitions.