National Book Festival (photos by Jeff Malet)

By • May 3, 2012 0 2625

The people who worry about the future of books and reading—myself and thousands upon thousands of other book lovers —may have less to worry about than they think.

Every year for the last 11 years, the National Book Festival, founded by then First Lady Laura Bush, has assuaged some of the fears that books and its attendant contents—stories, novels, poems, children’s tales, fables, histories, biographies, essays, short stories—are rapidly dying. From modest beginnings, the festival can now boast over 100,000 attendees —a huge number of them young people down to the just-beginning-to-read age—a statistic that probably caused the sponsoring Library of Congress to expand the festival to two days.

In less than ideal conditions—it rained sporadically and the ground on the National Mall was muddy in many spots—thousands again turned out, many parents with little children in tow, to hear authors read, take questions and sign books, to visit billowing white tents, to play games, to pose with a Penguin and other characters, to take quizzes, to grab tote bags and posters, and to give hope to the future of reading and books.

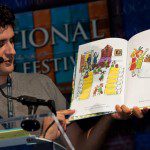

Among the many things the festival accomplishes every year is to shine a light on the great diversity of writing (and illustrating) talent that exists, authors who write great, big, and small, and lasting volumes of books. Over 100 authors, writers of all sorts and illustrators were on hand for the festival.

The lineup at this year’s festival looked like a representation of a golden age of writing, not a decline in the reading and penning of words and books. There was Toni Morrison who is as close to a world supernova literary star as you can get at such a gathering, making her first appearance at the festival, a treat for everyone who got a chance to hear her on Saturday morning. She won the 1993 Nobel Prize for literature, and she’s a unique and much-honored novelist and chronicler of the African American experience with such books as the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Beloved,” “Song of Beloved” and most recently “A Mercy.”

On Sunday, there was David McCullough, the venerable historian and biographer of presidents like John Adams, Harry Truman and Theodore Roosevelt, whose most recent book “The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris,” told the stories of American intellectuals and artists and their experience in Paris. For some, McCullough’s biography of the irascible, American-spirit to the core Truman may be one of the finest single-volume biographies of an American president ever written. Edmund Morris—who may have written the best three-volume biography of an American president with his chronicling of the life of Theodore Roosevelt – was also on hand.

In between, at a variety of tents and pavilions you could find mystery writers, children’s books writers and illustrators, poets, novelists, essayists, writers on politics and the contemporary experience, journalists who write books and collections. Washington Post-ies were prominent, among them op-ed writer Eugene Robinson and reviewers and essayists Jonathan Yardley and Michael Dirda. The red-haired, be-freckled and beautiful actress Julianne Moore was on hand to talk about her three books featuring “Freckleface Strawberry,” not coincidentally inspired by her own sea of becoming freckles.

There was Gregory Maguire, the man who gave us a book called “Wicked”—a dark other-side story about the witches of Oz—and thus can be held responsible and receive the accolades for the roaring theater musical machine that is “Wicked.” Sara Peretsky, the Chicagoan who invented the tender-tough (mostly tough) female private eye V.I. Warshawski was on hand again.

On both days, you could wander among the many pavilions and hear and see the sounds of the future of books, literature and reading. Often, the sounds were squealing noises, but still, a reaction is a reaction. Wells Fargo, a co-sponsor, had a booth complete with story-telling about old stagecoach days. There was a book nook, a digital vehicle and pavilion, telling about the history and holdings of the Library of Congress, there were bigger than life (and alive) furry characters (including the Penguin of Penguin books), with whom little kids posed. There were also drawing activities (it seemed often that there must have been thousands of crayons created for this festival).

What was exciting was the the variety and diversity among the pavilions. You walked into the mystery tent and there was novelist Russell Banks (who sometimes writes novels that fit this the genre) reading from one of his books, his beard bobbing in the light, the audience enthralled in a moment of story-telling. There were lots of stories told, including in a pavilion devoted to nothing else but story-telling. There was the yearly Pavilion of States, where the literary history and the current offerings were on display as huge crowds made their way through each state.

Claudia Emerson held forth on her poetry, and earnest men and women walked up to a microphone to ask her about how she revises and for a few minutes, you were treated to a talk about process, how poets can be made and un-made and changed. There were at least 200 people in the tent, many of them makers of poems, and all of them people who read or listened to poems.

There appeared not to be too much talk about the presence of new delivery systems that are not books, but contain the contents of books.

There was, in the end words upon words, and books with the words in them.

- Garrison Keillor | Jeff Malet