Through the Post-Impressionist Lens

By • May 3, 2012 0 4881

Post-Impressionism is a movement that often diverges the innovations of the collective whole among its individual artists. The painters are known and respected— Cézanne, Gauguin, van Gogh, Seurat—but their styles varied wildly and their directions were individually effusive and disparate. They also thrived in the precarious decades between Impressionism and Cubism (roughly 1890 – 1910), two of the most profound, loud and influential art movements of the past 300 years. As such, they are frequently and easily unhinged from their art historical parameters in museum settings.

“Snapshots: Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard,” the newest exhibit at The Phillips Collection, deals extensively with the Post-Impressionists, rethinking the movement and redefining everything in its wake. It not only solidifies the distinct and long-term influence of Post-Impressionism, but illuminates the profound artistic impact of a landmark technical innovation from 1888: the Kodak handheld camera.

The amateur camera made it possible for a broader public to capture daily life in snapshots, and in the hands of painters the door was opened to an entirely new understanding of composition, value and spatial relationships that reenergized the artists’ methods and creative vision. “Snapshots” presents works by seven of the first artists to experiment in photography: Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Félix Vallotton, George Hendrik Breitner, Henri Evenepoel and Henri Reviére.

This exhibition is the first of its kind, presenting over 200 photographs along with about 70 paintings, prints and drawings by the artists who took them. We are brought into the world of photography at its inception, and through these artists we see how the Kodak altered the perspective of our cultural lens. Even without a single work by Picasso, Braque or Duchamp, the urgency of cubism to resuscitate the future of painting becomes pertinently clear. We feel just why fine art began moving so quickly, without ever stopping to look back.

Entering the exhibition, you come upon a handful of small paintings by Bonnard. One is a portrait of the artist’s sister and brother-in-law. They sit smoking in a sharp, stark light, and at the bottom of the canvas is a large hand holding a pipe. It comes from outside the canvas, presumably belonging to the artist.

Immediately, we get an understanding of a photo-influenced composition. The figures act as compositional devices rather than subjects. As in a Rothko painting, Bonnard’s family members become strategically placed shapes that support an abstract harmony.

The perspective of the artist’s own hand and pipe is not a view Bonnard would ever have had before his canvas, but only if he put his hand before the camera lens. There is also radical foreshortening of the figures in space, making the painting almost graphic, illustrative or claustrophobic—we are contained in the space with them. This is the cropping and lighting of a photograph.

Sure enough, Bonnard primarily photographed his family and immediate circle of friends at home or during summer days in the countryside, examples of which abound in the exhibit, many strikingly similar to the scene in the painting. The eye of the camera, as it seems, is a contagious and invasive visual filter. It didn’t take even a decade to alter artists’ sense of space.

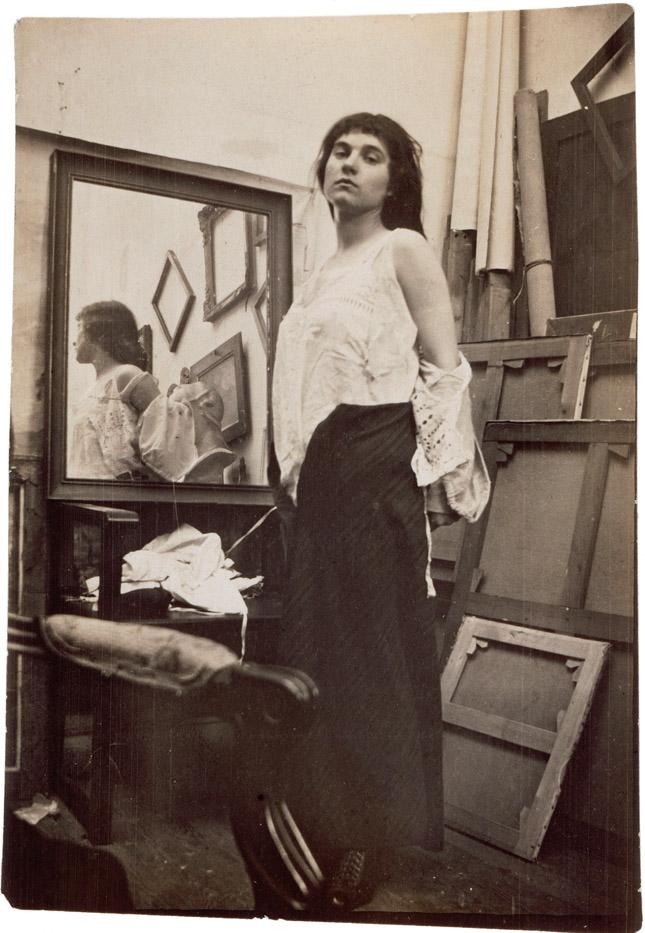

Walking through the exhibit, these moments reoccur and overlap: we see photographs that look like studies for paintings, paintings that bring together surrounding photographs, sketches and prints filtered through a camera lens. To these artists, photography was still a mimetic medium, used to better understand their paintings—to clarify a perspective, to study the shape of a figure or the dimensional accuracy of a mirror’s reflection.

Photography was initially frowned upon by critics, which made the artist’s reserved about revealing their work with it, which is perhaps why most of these photographs have never before been on exhibit. It is interesting, though, that even within this exhibition we start to see a certain superfluity of the paintings, not the photographs. However beautiful the paintings are, the act of painting what is captured in the photograph becomes redundant.

Breitner’s photographs, among the others in the show, are in fact more compelling than his paintings. A pioneer of street photography, he focused on the city as a visual resource: his street scenes of carriages, canals, sand carters and mill workers, construction and urban bustle, are some of the most moving images on display.

In the work of Vuillard, the marriage of painting and early photography becomes almost seamless. His photographs of family and friends, posing in the mundane theater of quiet existence, sit alongside his paintings of domestic moments. They inform one another, communicating to its audience the artist’s world and vision. The works in this room serve also as nice companions to similar Vuillards currently on view in the National Gallery of Art’s “Small French Paintings” exhibit.

“Snapshots” comes at a unique time, as Kodak files for bankruptcy and digital photography poises to monopolize the industry, leaving traditional film with almost no place in contemporary culture. But just as oil paints took the place of tempera and egg-based paints in the 15th century, the takeover of digital photography does not negate the impact of the precedent set by film. The introduction of photography altered our perceptions of our surroundings, but it took a group of painters to reveal the potential of its beauty.

Exhibiting the works among this subset of Post-Impressionists showcases an important development within a movement that is often difficult to pin down, concentrating the significance of the exhibition as well as the unity of these artists. These works seem in many ways like the sparks that set off the explosion of 20th century art. And yet here they hang, delicate, pensive and ethereal, as if standing on the precipice of an endless free-fall without thinking to look down.

“Snapshots: Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard,” is on view at The Phillips Collection through May 6, 2012. For more information visit PhillipsCollection.org