Richard Diebenkorn: Everything All At Once

By • September 21, 2012 One Comment 5699

The moment I saw the paintings of Richard Diebenkorn for the first time was one that shifted the course of my life as an artist. I was an 18-year-old student wrestling with things like color, form and, more onerously, ways to convey my ideas and break free from the self-aggrandizing egotism that artistic practice so easily brings about. Something in the style of my complaints must have triggered my teacher to offer me a book of Diebenkorn’s work. I had never been so affected by paintings.

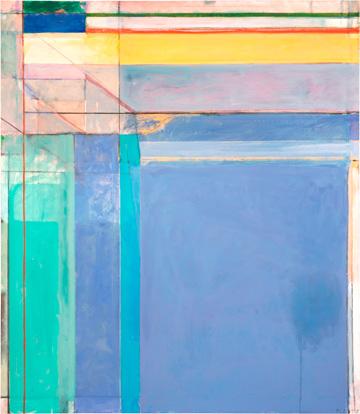

Even in the cramped dimensions of a catalogue, his works felt huge—they carried the visual grandness of a mural in a few square inches. His endless washes of color, falling through and beneath one another in farm-like grids, conveyed a vibrant and somehow weathered atmosphere, like sunlight piercing through morning fog. It was dilapidated doors, smoke, hot asphalt, sweat, fields, style, color, shape, geography, line, form, joy, peace, war. It was paint. And it had never looked better to me.

I remember wanting to run my hands all over these paintings, these fields and strips of color that looked like Mondrian charged with a scuffed, pulsing static. I wanted to lift up the veils of yellow paint to explore the oceans of red ochre and blue-grey beneath the surface. Diebenkorn lets viewers into his process in this way, allowing us to know his paintings inside and out—and he offers this portal to us without reservation or anxiety. In his time, Diebenkorn was a famously generous and patient teacher, and this comes out in his work—even his paintings are good teachers.

Unlike so many artists of the past century who went to great lengths to hide their techniques, Diebenkorn unveils his methods to us garnished on a plate. This was a man who wanted painting to survive when others denounced it as dead, to move the arts into the future in a way that connected and involved audiences.

For the second half of the 20th century, Diebenkorn was the painter’s painter. You would be hard pressed to find a working artist today that does not adore this man’s work. It is painting as the idea in itself, which seems to speak about everything—about an artist in his environment, but also about things transcending any singular time, place or individual. “The idea is to get everything right,” Diebenkorn once said, rather prophetically. “It’s not just color or form or space or line—it’s everything all at once.”

Take a moment to spend time in front of his paintings and you will know what he’s talking about.

Through the end of September, the Corcoran Gallery of Art is hosting “Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series,” a retrospective of the artist’s landmark series made between 1967 and 1988, which marks the first major museum exhibition focused on these luminous, grid-like paintings. Small works on paper, prints, drawings and collages—even some “cigar box” studies—share space with his signature massive canvases, many of which are over eight feet tall.

“These works are powerful investigations of space, light, composition, and the fundamental principles of modern abstraction,” said Philip Brookman, chief curator and head of research at the Corcoran. “Diebenkorn investigated the tension between the real world and his own interior landscape… These are not landscapes or architectural interiors but topographically rooted abstractions in which a sense of the skewed light and place of that time emerges through the painting process.”

A lifelong inhabitant of the west coast, Diebenkorn (1922 – 1993) served in the U.S. Marine Corps after attending Stanford University and afterwards took advantage of the G.I. bill to study art at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. Among his teachers was Mark Rothko, the acclaimed abstract expressionist who doubtlessly effected his perception of modern art. A look at Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series leaves no doubt that Rothko influenced his sense of composition and color palette. (And as The Georgetowner’s Gary Tischler often points out, “Washington is the Rothko City.” All the more reason to welcome this show to our town.)

As a young painter in the 1950s, it was no small feat to reckon with the wild assault of abstract expressionism on the contemporary art scene. To come into your own at the tail end of one of art history’s most explosive, brazen and contentious periods was a considerable strain on many emerging artists. But with that pressure came a certain liberation for Diebenkorn. Willem De Kooning later would say that the abstract expressionists (and Jackson Pollock, specifically) “broke the ice”; afterwards, art could go anywhere and be almost anything.

During this time, however, Diebenkorn did a rather unusual thing: he pioneered a representational movement, at once a gesture to the tradition of art history and an outright rejection of modern art critics like Clement Greenberg, who argued for “advanced art” that renounced subject matter and representation for the “purity” of abstraction.

Along with fellow artists such as Wayne Thiebaud—most recognized for his over-saturated paintings of cakes and patisserie treats— they together founded The Bay Area Figurative Movement, which pioneered an expressive, representational style that brought together the thick, lustrous brushwork and wanton impasto of abstract expressionism with the earthy romance of the Impressionists.

Though a far cry from his later work with the Ocean Park series, Diebenkorn began in his early paintings a pattern of weaving the threads of familiar people, family members and California landscapes with a grand intimacy that connected his quiet, precise observations to the collective subconscious of postwar America. It was a mutual search for peace, balance and beauty. He learned what it meant to be a modern painter as the world around him learned to see as a modern audience. His work was met with acclaim from critics, viewers and patrons alike.

In the mid 1960s, Diebenkorn took a teaching position at UCLA, moving from San Francisco to Santa Monica. It was during this time that he moved away from his figurative style, for which he had by now become quite popular, and began work on his Ocean Park paintings, a pursuit that would last him the rest of his life and become one of the most influential bodies of work in the second half of the 20th century.

Named for the beachside community where he set up his studio, the Ocean Park series cemented Diebenkorn at the forefront of his generation as an artist dedicated not just to his own work, but to the history and future of his medium.

The shift happened gradually but surprisingly, according to the artist, and in a way he always had trouble explaining. “Maybe someone from the outside observing what I was doing would have known what was about to happen,” he said in an interview in the late ’60s. “But I didn’t. I didn’t see the signs. Then, one day, I was thinking about abstract painting again… I did about four large canvases—still representation, but, again, much flatter. Then, suddenly, I abandoned the figure altogether.”

But looking at these paintings, what we see in fact is an unprecedented balance of abstraction and representation. These paintings are not just shapes that resemble things, like looking up at the sky and seeing a cloud shaped like a poodle. They are distillations of whole environments from which they are born.

Within the canvases are the layouts of suburban neighborhoods, the aluminum siding and split-level houses of mid-20th century America, power lines and clotheslines, interstates and parklands, oceans and shorelines, even the great frontiers of the Wild West. But while these visual tropes are tangible and intriguing, no one theme sits within any particular canvas. You will not find a painting in this exhibit titled “House by the Sea.” Diebenkorn named each piece in this series with a number in the order by which he made them.

The numbers become markers of the passage of time that denote the changing and shifting of the artist’s environment as he lived it. Just as Monet painted the Rouen Cathedral in different lights of day and Matisse evoked the emotional sentiments of his era with the wild, dissonant color palette of Fauvism, so did Diebenkorn acknowledge his time and place by sweeping his brush across his own physical and cultural landscape. He captured the grand, clean-shaven, perhaps diluted idealism of his time in wash- worn, infinitely expansive color fields, cut up with arbitrary vanishing points and the stark measurements of clean, straight lines.

Still, the paintings impose almost nothing upon us as viewers. We are free to explore the pictures in our own way and at our own pace. Diebenkorn’s postwar American abstraction offers glimpses of harmony and calm, a generalization of that “American Dream,” the sincerity and earnestness of which has not really been seen since.

I still wrestle with the same issues as I did when I was first introduced to Diebenkorn’s work, but he helped me to learn that these artistic dilemmas are not just equations that you solve and move past. These issues are themselves the pursuit of art. Diebenkorn’s work inspired me beyond myself. When that happens, you cannot help but to believe in art. ?

- Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park #79, 1975. Oil on canvas, 93 x 81 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art | ©The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation.

Thank you for the article on Diebenkorn (2012)! Painting was probably always a lonesome endeavour, however today it is more like solitary confinement. The voices of Diebenkorn, De Kooning, Martin and others keep me sane. Your voice is different. Can I subscribe to your newsletters?

Kind regards

Maria