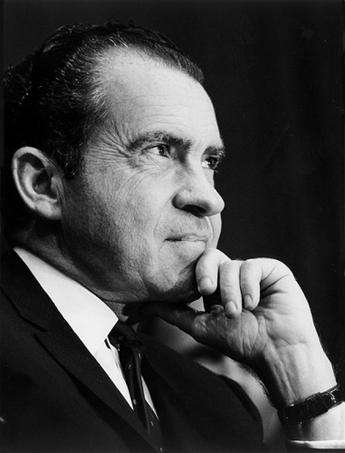

Remembering Richard Nixon on His 100th Birthday

By • January 15, 2013 0 2086

Richard Nixon was never easy to dismiss, forget, defeat, or ignore even unto death.

For a brief time last week, there was a flurry of articles, reports and buzz in what passes for our muddled media mass today—news stories in newspapers, passing comments on the network news, buzz, buzz, buzz on the internet. Richard Nixon was, for a short time, back in the news, because some 400 of his friends, staffers, family members, loyalists and prominences during his not-quite completed two terms of office as President of the United States gathered to celebrate what would have been his 100th birthday.

Henry Kissinger was there, Tricia and Julie, the daughters were there, at the Mayflower, were, ironically during this time of the upcoming inauguration, Nixon balls were held in the same venerable space. We read the reports in various places, including the Washington Post, where the occasion made the Reliable Source, not the front page. Pat Buchanan, the pugnacious Nixon speech writer famous in later life for outrageous to the right of Nixon punditry, was the most tenacious defender of Nixon and his legacy and Kissinger, the man most elevated to prominence by Nixon as his National Security Adviser and Secretary of State back in the day, extolled his foreign policy greatness, not the least of which was Nixon opening China to the U.S. and vice versa, because, as the saying went then, “only Nixon could go to China.” This was after all still a country led by Mao Tse Tung back then.

Nixon’s brother showed up to give a victory sign, his daughters praised their dad, and Buchanan talked about the “old jackal pack” who brought Nixon down. Somewhere, Woodward and Bernstein were talking about Watergate and the Nixon tapes, which Woodward once called the “gift that keeps on giving.”

Nixon, famously, infamously, of course was the only president of the United States to resign his office to avoid impeachment a result of the umbrella scandal called Watergate, which included dirty tricks, a burglary of the DNC offices in the Watergate, a coverup, firings, resignations, jail time for some, and the wholesale destruction of careers. Forever after, scandals would have a gate tied to their names as in Irangate, Whitewater gate, and so on. All this, after Nixon, a former U.S. Congressman, Senator and two-term vice president under President Dwight Eisenhower, made a remarkable political comeback, winning one of the closest elections ever by defeating Hubert Humphrey in 1968, then again by scoring the biggest landslide win in the history of presidential elections over George McGovern in 1972. Talk about rescuing defeat from the jaws of victory.

It would be easy to dwell on “Tricky Dick”, “Watergate”, the extension and escalation of the Viet Nam war by way of ending it, the “you won’t have Nixon to kick around any more” debacle in California, the bad diet (ketchup and cottage cheese), the betrayals, the denials and cover-ups, the Checkers Speech, to focus on that Nixon the press loved to hate—and the feeling was mutual.

But I’m more inclined to take the late Tom Wicker’s view in his more or less biography “One of Us”. Nixon is endlessly fascinating—like LBJ and not like LBJ—for his complexities, for his persona and his conflicting achievements. But if we are truthful, most of us—males—don’t look in the mirror and see JFK, but we might recognize aspects of Nixon’s flawed face instantly. His small beginnings in a small town in California, his love of his mother, being a manager, not an athlete, his outsized use of profanity as evidenced on the tapes, that strange awkwardness he carried around with him, even unto the presidency, were traits shared by many. He had no flash, no flair, no charisma except the kind of scowl that predicts bad weather.

And yet, no man was better prepared for the presidency, better ready to think in visionary terms—he created the EPA and his domestic and economic policies tended to benefit the middle class, not the rich. He was no ideologue (his anti-communism may have been fervent but it had its expedient political uses), no right wing fundamentalist, no Barry Goldwater, no Tea Party guy, who probably would have found him way too liberal for their give-no-quarter tastes.

Here was a man who endured a kind of paternal dis-respect from Ike, who saw fit to use his dog and his wife’s coat to stave off being dumped from the GOP ticket, who had to say as president that “I am not a crook”, who rashly ran for governor of California after enduring a heart-breaking, nail-biting defeat at the hands of JFK and yet, there he was, in 1968 and in 1972, winning the presidency.

He could have—given some of the more questionable aspects of vote counting in Illinois and Texas in the 1960 election—asked for a recount, so close was that election. He chose not to because such a challenge might have torn the country apart.

He showed courage often—getting into Chairman Kruschev’s face, enduring the mobs who rioted in Venezuela on his visit there. He was an awkward man, that’s easy to see, but he became, in the end, a grandee in one of those Wall Street law firms that practically says Wasp on its letterhead. He could be maudlin and sentimental, always considered cheap emotions by the intelligentsia of a better class but he had his loyalists and loyalties.

If you throw out Watergate, he might be counted as one of our more effective presidents—hard to say since you can’t throw out Watergate or Nixon. It’s not the only questionable thing he’s associated with, only the worst one.

For many of us, he remains the difficult ghost in the machine that we call democracy, and, like the man said, one of us. He does not speak to our better angels, but rather to our more complicated memories.