Seventies Exhibit at National Archives

By • March 25, 2013 0 1629

The more distant the recent past becomes, the more it tends to appear in our immediate rear view mirrors.

In America, we often suffer from selective memory, bracketed by convenient decades, or categories—Reagan’s Eighties, the transforming, revolutionary 1960s, the conforming, placid Leave-it-to-Beaver-disrupted-by-Elvis Eisenhower 1950s, the Greatest Generation, WWII, the Great Depression, the Roaring Twenties, and so on.

Rarely do the Seventies appear in that mirror with any intensity, and when they do, the images are thought to be grey and indistinct, the music bland or discordant, the cars too long and the gas lines longer. There’s a certain disdain and disconnect that’s accumulated about the decade, as if it was mildly depressing with signs of American decline appearing like pimples on a once confident teenagers face, it’s as if nothing much happened, and whatever happened, we’d just as soon forget about it and move into Reagan’s morning in America.

So what are all these folks doing here, many standing in line waiting to get into the National Archives last Friday?

Most of them were waiting to see the new exhibition “Searching for the Seventies, the Documentary Photography Project,” showcasing some 94 photos from about 22,000 taken by 70 photographers from 1971-1977.”

The title alone suggests that the Seventies haves gotten lost somewhere in the overcrowded American imagination which now feeds on reality shows that aren’t real, access to everything and connection to all, mostly without focus.

The documentary photography project is reminiscent of similar Depression Era efforts, including the classic James Agee/Walker Evans book “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men,” as well as the Roosevelt era Farm Security Administration’ photography program. “In Search of the Seventies” was a project of Documerica, which in turn was funded by the new Environmental Protection Agency, it had as a goal the idea of dealing with the energy crisis, a nascent spirit of environmentalism, urban renewal, economic crisis and challenges and the role and the rights of new political and social movements and identity by women in an America whose diversity in terms of racial, ethnic, gender and sexual identity, diversity was rapidly becoming visible and active.

Put that way, the project, instigated by EPA public affairs employee and former National Geographic photo editor Gifford Hampshire and headed by National Archives curator Bruce Bustard, seems almost dry and political.

It’s anything but that—while its focus seems to be on environmental issues—it appears to have reshaped the meaning of the word environmental to include the American human landscape, the human face that reminds us of ourselves over a period of ten years that were anything but uneventful. The result—as seen in the nearly one hundred photographs—is a look at how and in what ways and where Americans lived in a changing environment—the literal one as well as the metaphoric and social one.

On the day of the exhibition’s opening last week, there were lines, and inside, the seventies crowd mixed with young professionals, people who had brought their kids late in the day, and surely many of us who saw some vestiges of our younger selves in the photographs. “Oh my god,” one woman said, “there’s my Buick Skylark”. Cars, in fact, play a large role in the exhibition—as polluters, in a massive junkyard piled like GM auto corpses on top of one another, as rusted and abandoned by the side of a road in Arizona, as sleek, long American cars as proudly displayed in front of a garage in Lakewood, Ohio.

“Searching for the Seventies” isn’t necessarily about the dangers to the environment per se—although it came about a year after the first Earth Day was held, the EPA was signed into existence law by Richard Nixon. The photographers—all working with color, all of them gifted and talented—had a broad mission to follow what they were interested, what their lens and hearts saw, or so it seems judging by the results, some of them with very specific assignments. Broad themes are also here—“Everybody is a Star”, “Ball of Confusion”, “Pave Paradise”, alongside the specific journeys Jack Corn moved through Appalachia—traveling through West Virginia, Kentucky, and Virginia, coal mining territory, where he photographed the miners, their plights their families, many of them suffering from black lung disease, or the dangers inherent in the grueling work they did. There are miners. There’s a pool hall. There’s the hopeful young face of Clarice Brown, 19, who worked as a secretary for the United Mine Workers in Charleston, West Virginia, the man with the red helmet and lamp in Virginia-Pocahontas Coal Company #3 close to Richlands, Virginia.

There’s John H. White, the Chicago Daily News photographer who shot images of Chicago’s black population and neighborhoods, which struggled with poverty but also exuded a new vibrancy captured by his lens.

There’s Lyntha Scott Eiler who went on assignment to Arizona, especially in the north, capturing development surges, Native American children, the effects of strip mining and the smoke from power plants.

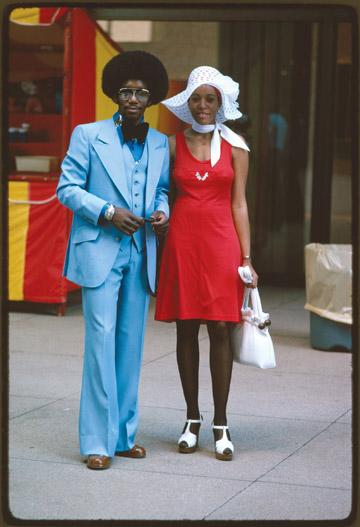

And then there’s Tom Hubbard, who once worked for the Cincinnati Enquirer and returned to his old stomping grounds to find a little bit of the soul of 1970s America in Fountain Square, an all-purpose square and park in downtown Cincinnati, which appears not so much as a specific place but a generic American place with a fountain, benches, musicians and jugglers, lunchers and people playing chess and protesting and carrying signs, much as you might find at Freedom Plaze, Dupont Circle or Farragut Square. The clothes look different, hats are from then not now, and dresses are as short as they are now and bell bottoms are the rage among dudes.

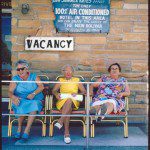

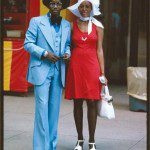

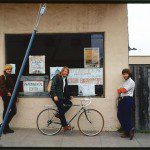

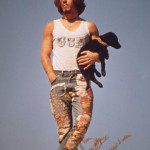

In a section called “Everybody is a Star”, you see the emerging people who fueled some of the outbursts of change in the 1960s—protesters, a man with a t-shirt emblazoned with a USA logo, wearing tie-dyed pants, sporting a beard and muscles and a black lab puppy. You see them all, rising up, the young black couple, he in a blue suit, topped by an Afro, she in bright red dress, three women sitting outside a retirement home in South Beach, farmers keeping safe during a dust storm, migrant workers, a bright-eyed teenager in her bedroom in Meeker Colorado, a guy selling Italian Lemonade.

You don’t necessarily hear America singing.

Actually, it’s John Fogerty and Creedence Clearwater Revival or Linda Rondstadt, bawling her man out with “You’re No Good, You’re No Good”—or Carole King going on with “I feel the earth move under my feet” as you move along.

What you see is planes, trains and automobiles, people waiting in line for a Metro shuttle in Bethesda, the smoke and rust of factories, run-down neighborhood, small towns hanging on, diners and the freeways of America.

What you see in the rear view mirror is the daily rhythm of change in America, moving out of the sixties, trudging toward the eighties. What you see in this rear view mirror is a younger face, looking vaguely familiar.

- “Michigan Avenue, Chicago” (couple on street) Perry Riddle, Chicago, IL, July 1975. | . National Archives, Records of the Environmental

- Jordan Wright