Almost every biographical reference you can find on John Carter—the ones that don’t lead to the fellow who spent time on Mars—tend to lead off with a colorful, intriguing picture, as does the one in the program for his new play “I, Jack, am the Knave of Hearts,” which begins: “John Carter (playwright) is also a poet as well as a former merchant seaman, railroad man and wordsmith for hire who has ceased his wanderings and now lives out of sight with his wife and dogs.”

Somehow, the merchant seaman, railroad man and wordsmith are the grabbers. It’s resonant of the kind of creative types who live fully, breath smoke and traveling air, have seen and done things most of the rest of us mortals haven’t. All of this and the rest of the biography you may read is true and important. Yet it’s more like the beginning sentence of a novel, or better still, a play.

The dog part is true, and more importantly, the playwright and poet part are gloriously true. Carter is also an actor who’s played cops in films and on stage and has performed his poetry on stage in Washington in “various dives with the rock groups Eros and Luna and solo in more polite venues, including the Library of Congress.”

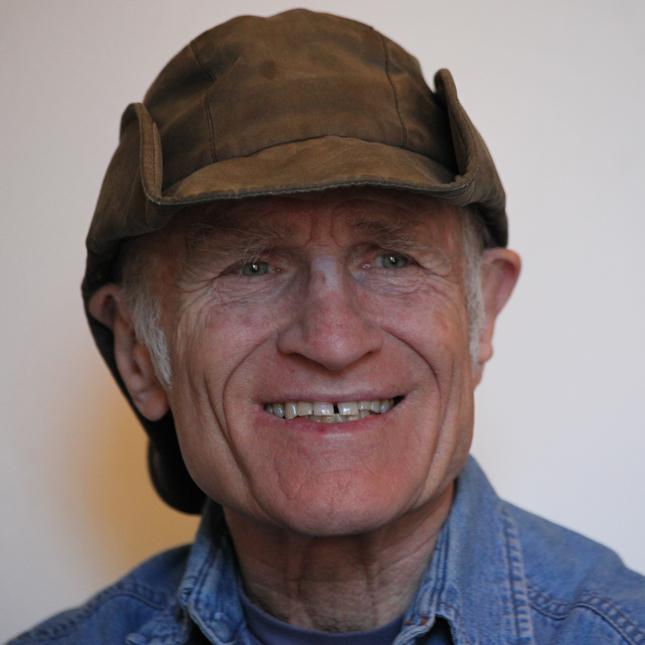

I met Carter in my D.C. neighborhood of Lanier Heights some time ago when we were walking our dogs. Carter looks a little like his biography—smallish, lean, blue jean jacket, a trademark wind-bitten Aussie hat. We met through Ruby, his brown, energetic poodle and my bichon Bailey, who has since passed away. Once our dogs were properly introduced, we discovered mutual interests and common experiences which we shared over coffee and over time. One of those interests was theater.

At the time, Carter was involved in staging an earlier play he had done (there have been four altogether), called “Lou,” a one-man play about Lou Salome, a dazzling woman, contrarian intellectual, muse, companion and sometimes lover to the likes of Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud and the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. “Lou” was staged in New York and at the Fringe Festival there. It was performed by Elena McGhee.

In many ways, “Lou” is a remarkable play because of the way it appears to get at the heart and soul of a remarkable woman—a daunting task for any male writer. “I tried to imagine everything that happened to her, everything she talked about from the standpoint of a woman,” Carter said, as if that’s the most natural thing for a male writer to do.

While Carter has written all of his life and been a poet for many years, playwriting is new to him. He is, after all, in his early eighties—82 years old, to be exact. For him, there is still a lot to do in this arena. From “Lou,” Carter tackled something a little different, which eventually became “I, Jack, am the Knave of Hearts.”

“ ‘Lou’ took a long time,” he said. “ ‘Jack’ practically came to me in a rush. It’s a work of the muse. I can’t explain it in any other way.”

Jack is Don Juan, or Don Giovanni, or perhaps all the great philanderers, womanizers of history rolled in one. He is time specific as played by D. Stanley, who is the artistic director of Theatre Du Jour and who also directs. All over Adams Morgan, these past few weeks, we’ve seen cards and posters, at bookstores or galleries or even a shoe repair shop for “Jack,” seen as a darkly-dressed, time-driven swaggering mystery man with a sword, whom you can see at the District of Columbia Arts Center on 18th Street.

The play closes this Saturday, April 6, and has been marked by a roller coaster ride that is a a lot about the life of Carter, the play itself, writers, and Adams Morgan. It’s also about the special qualities of the DCAC, which doubles as an art gallery and has seen the presence of many of Washington’s troubadour theater groups like Scena, Venus, the Landless Theatre Company, and the outrageous and lamented Cherry Red Productions, as well as appearances by burlesque and vaudeville performers.

“We’ve been reviewed twice,” Carter said. “Once negatively, which isn’t much fun, and once positively, which is gratifying. We’ve had good houses, and not so good houses—there was one time when the only people there were three kind of scruffy old guys, which made it difficult for Stanley, because the reaction of women in the house is important.”

“Jack” is a one-character play which sees Don Juan escaping from hell, in a bravado-like confusion, and trying to make sense of the life he led that landed him in hell, and the particular qualities of hell. He wears an open white gallant’s shirt, black boots of the striding kind and carries a spectacular sword and arrives with an attitude.

I saw the play on a night when Carter’s wife Julie Bondanza, a Jungian analyst, was there, seeing it performed “for the first time,” along with his daughter, assorted relatives, a member of the Playwright’s Forum to which Carter belongs, neighbors and walk-ins. The presence of a number of women in the audience seemed to invigorate Stanley, whose Jack was a man in search of his own identity, energetically striding the stage like an adventurer, looking over the fleshly highlights of his life, the death of his mother at the stake, the seduction of a woman and the murder of her father. On the simple, brightly lit, dark-background stage, the search seems to be the one we all march on, in our dreams, in those moments. “I begin to know myself,” Jack says and at another point, notes that “Hell is the end of hope.”

Carter didn’t attend rehearsals. “I like to be surprised,” he said. But he was sitting in the back listening and watching intently, laughing at the laugh lines as if discovering it again, like a true audience member, for the first time.

At play’s end, you walk into the gallery, where a reception for artist Joanne Kent’s amorphous works on the wall is in full swing and swagger. The crowds don’t part, they mix and talk and merge, art not so much imitating life as joining it.

The Knave of Hearts is surrounded by people. John Carter is surrounded by friends and family. The words still seem to be a part of the night, the cool air, hanging there… “A man back from the other side of hell, a man you hide your daughters from, a man with bloody hands. Am I that man?”

That night, he sure—as hell—was.