‘Over Under Next’ Experiments in Mixed Media 1913 – Present

By • September 12, 2013 0 1837

It is important to believe that something significant can be born out of us, because we ourselves are significant. We are an active part of our environment, and so we absorb and affect both its landscape and its ephemera. When we create something, even while fiddling absentmindedly with one odd distraction or another, we intuit the possibility for a greater conclusion to come of it, pulled out from the life which courses through us. To be really pedantic about it: Asserting the natural filter of consciousness is important to the pursuit of things like abstraction, which depends on the ability to communicate something that is inherently not communicable. A different way to think about it might be: Our heads are overloaded with great and often untellable stuff, and if we are lucky we will someday find a way to get it out in the open.

In a unique and refreshing manner, mixed media in art brings the artist’s misplaced ideas and subconscious thoughts together with the very objects and materials of their world. It goes beyond painting or sculpture, wherein an artist creates every shape, line and color to reach their conclusion. With mixed media the content already exists, waiting to be assembled. The art form is quite new, co-invented in the early 20th century by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. According to the Guggenheim Foundation, the glued-on patches of wood, cloth and other materials that they added to their canvases offered a new perspective when they “collided with the surface plane of the painting.” The practice was discovered by many artists to be a useful new manner of visual communication that interacts directly with the surrounding environment.

“Over Under Next, Experiments in Mixed Media, 1913 – Present,” an exhibition at the Hirshhorn through Sept. 8, explores this medium from its creation in the early 20th century through today, demonstrating how artists continue to deal with their rapidly expanding world in beautiful new ways.

The first room in the exhibit is a trove of delicate and forgotten artifacts of modern art—an appropriate tone to set the direction of the show. There is of course a Braque, a 1913 painting collage of a violin and sheet music, which resonates as the catalyst for the ensuing journey. There is also a large-scale 1959 work by Robert Rauschenberg, perhaps the most renowned mixed media artist of all time. His innovative “Combines” of the 1950s employed non-traditional materials and objects, from photomechanical reproductions, to cloth and metal on canvas.

These works bookend some smaller compositions by a handful of highly influential, if lesser known, artists of the early 20th century: Kurt Schwitters, Hannah Höch, Joseph Stella, Man Ray and George Grosz, among others.

Born in Germany in 1913, Schwitters incorporated refuse that he scavenged from the streets into paintings, collages and even poems. Merz, Schwitters’s one-man art movement, was rooted in a desire to create connections between all things, using printed ephemera, rubbish, and found materials. In “Milwaukee” (1937), his complex design combines elements of nonsense and chance from the Dada art movement with unusually strong design properties. Leaving Germany in 1937 due to the deteriorating political situation, his work was radical enough to earn censure as “degenerate art” by the Nazi regime.

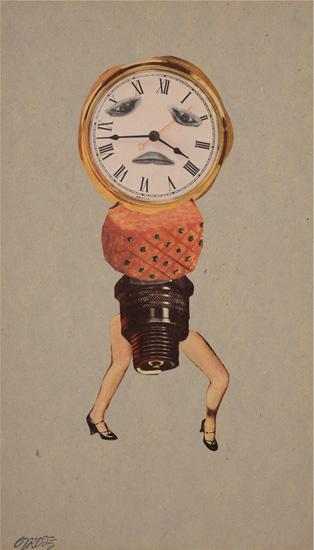

World War II ends up playing a supporting role in this exhibition, as the political landscape and accompanying propaganda of the Nazi party became inescapable fodder for mid-century European and American artists. Höch and Grosz were German contemporaries of Schwitters and members of the Dada movement, who employed collages to respond to their country’s societal upheaval. Grosz’s brutally comic “Clock-Faced Woman” (1953), with its assemblage of human facial features forming a devastating frown on a clock face with pinup girl legs, is reminiscent of his savage caricatures and political cartoons of German political machinations.

Hans Richter’s heavily political “Stalingrad (Victory in the East)” (1943 – 1944) is a large-scale panoramic collage that functions as a timeline of the war. Richter used English newspaper clippings with headlines like, “Nazi Lines Ripped At Stalingrad Front,” arranged in a playful composition of organic shapes and primary colors that recalls Alexander Calder’s mobile structures. Calder’s work is in fact displayed alongside “Stalingrad.”

An entire room is devoted to the work of Joseph Cornell, whose modern cabinets of curiosity act like dreamy funnels for displaced memories, desires and histories. The myriad works are so rife with subject matter of bygone eras that they feel like the diagrammed mind of an Alzheimer’s patient whose old memories resurface to displace the ones it has lost, intermingling with the static of the present. One piece shows us a map of the equator lining a shadowbox, with miniature glass goblets holding pearls inside and metal rings hanging from the top. Like much of the show, this is a body of work that must be experienced to fully understand. But then that is the beauty of art, and the significance of mixed media. It exists nowhere but in its own time and space, offering us a chance to understand our world in ways that escape us at the tips of our tongues.

“Over Under Next” will be on display at the Hirshhorn through Sept. 8.

For more information, visit Hirshhorn.si.edu.

- George Grosz, Clock-Faced Woman, c. 1953. Photomechanical reproductions and graphite on paper on cardboard. From the Hirshhorn’s collection.