Fusion at the Art Museum of the Americas

By • September 25, 2013 0 2354

Walking through “Fusion,” the recent exhibit of modern Latin American paintings at the Art Museum of the Americas, art historian and exhibit curator Adriana Ospina spoke to me about rice.

“In the United States, Cuba and South America, we consume a lot of it,” she said. “Rice in the Americas grew through the influence of Asian immigration in the 19th and twentieth centuries, and now it is just a part of us. No one talks about it, but that cultural influence is always present.”

After centuries of human migration throughout the world, history has long proven that the cross-pollination of coinciding cultures is basically inevitable. When two groups come together, they react by forming a new group built from their combined history and experience. Call it symbiosis, call it obvious, call it anything, but this occurrence is in many ways the engine behind a profusion of anthropological and historical knowledge.

Perhaps most obviously apparent in language, food and religion, this active cultural evolution bubbles beneath the surface of our everyday lives. There are infinite examples around the world, from the consumption of Indian tea in England, to the ever broadening and diversifying reach of the Catholic Church in South America, to the heavy influence of European justice systems on the United States Constitution.

With a focus on Latin American art during the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries, Fusion traces Asian migration to the Americas through art, generating a dialogue on cultural diversity by exploring its resonating effects on specific artists and their ancestors who relocated to the Americas from Japan, China, India and Indonesia. The exhibit enhances our perception of the complex and interwoven tapestry of modern Latin American and Caribbean societies, highlighting the exchange of ideas that this multiculturalism has generated.

In addition to (and aside from) the ambition of its social and cultural mission, it also functions strikingly as an exhibit based purely on the merit of its artistry. An audience can walk through admiring the paintings for their sheer aesthetic splendor, or take away a broader message of the rich and diverse societies of the Americas.

What is most interesting about the paintings on display in the exhibit is perhaps their conspicuous absence of political or social agenda. Many of these paintings are collegial equals of the more prominently known work of their day. The expansive canvases of Manabu Mabe (1924 – 1997), a renowned Japanese-born Brazilian painter, are truly on par with the groundbreaking work of the 1950s and ’60s. His paintings evoke the bravura brushwork of Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, and even Frank Auerbach, (with a surrealist tang of Dali or Miro), but with a unique expression that weaves a fluid and graceful line amid bursts of color and monochromatic backgrounds, which can be traced to Mabe’s practice of Japanese calligraphy.

Mabe, like many great artists (as a few mentioned above), was an immigrant, whose clash with multiple cultural institutions seems to have caused a creative eruption born from a natural inclination to codify environments and experiences. The difference is that Mabe is foremost considered as a Latin American artist in the European tradition, as opposed to an “artist,” unburdened by a genealogical addendum.

As Michele Greet, a Ph.D. in Modern Latin American Art, writes, “The tendency… has been to isolate Latin America as a geo-political entity in the conception of exhibitions, university courses, and scholarly texts… Studies of Latin American art thus tend to explain images produced in this region as motivated by a desire to promote an ‘authentic’ national or cultural identity and avoid in-depth consideration of migration, mixed racial heritage, and global interchange…”

She goes on to write that our understanding of this art is a “part of a global network of artists and ideas, rather than an isolated development,” for that is precisely what art in the modern era is. On the whole, modern art is not an overtly political vessel. It is a venue for exploration, analysis and interpretation that simultaneously sets us apart and brings us together. A work of art does not have to display a political message in order to incite cultural sentiment or political debate.

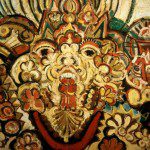

Communicating this idea so effectively is where Fusion ultimately succeeds. From the influence of Indonesian heritage on Surinamese-born artist Soeki Irodikromo (b. 1945), whose painting of an Indonesian dragon incorporates local motifs of the Surinamese jungle, to the faint connotation of Chinese ancestral veneration in the surreal lithographs of Cuban-born artist Wilfredo Lam (1902 – 1982), this exhibit shows us how our multifaceted pasts effect us as an undercurrent, influencing our lives without taking precedent over our personal progress and collective cultural evolution.

The Organization of American States, the parent organization of the AMA, has long upheld their mission to implement democracy, development, human rights and freedom of expression throughout the Americas, promoting the benefits of immigration and offering positive, enriching examples through community outreach, political discourse and, with the AMA, through art.

“Fusion,” as much as an art exhibit can, fulfills this mission.

And like the spread of rice throughout the Americas by way of Japan, most of us can agree that it is quite a good thing.

- Soeki Irodikromo (Suriname, b. 1945), “Untitled.” Oil on canvas. | Yelp