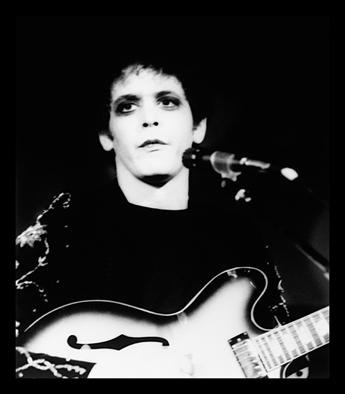

Lou Reed: Pervasive Rock Pioneer

By • November 7, 2013 0 1214

Lou Reed—who, it was said in an American Masters PBS special, brought rock and roll to the avant garde or is it the other way around—died just a few days before Halloween. Means nothing, but I hope somebody at some party puts on his lean, gaunt, hollow-eyed mask of a face, grabs a guitar and plays more than a few riffs of “Baby Jane,” or like a pied piper heads out into the night and the wild side, doo do doo, doo do doo, doo do doo.”

Reed, the Brooklyn native and world citizen of the wild side—as in “Take a Walk on the Wild Side”—and the Velvet Underground are in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There are a thousand reasons, because his name and music bounces around like a pinball wizard in all the tell-tale hearts of rockers and rockers as somewhat mad poets and rockers as intellectuals. He’s a legend in his own time, mind and New York, if not Graceland. He—and the Velvet Underground, the strange rock-out but dark, and darker group he led with violinist John Cale—wasn’t your typical rock and roll god, he was more like Loki than Thor.

According to the Rolling Stone obituary, Reed once said that his entire career, taken together amounts to a kind great American novel. Don’t know about that—”Moby Dick” is the big fish for me—but maybe it’s the Reed life and work that should be the subject of a great American novel, or e-book at least. So, get to it, somebody, before things get waylaid, misquoted and forgotten.

The Washington Post obit dubbed him “The Velvet Underground Visionary.” While that is true, I think he was more than that. Everywhere you look in the nooks and crannies of rock and roll, the New York art scene, in the generals of the defiant punkers, the glams (hello, David Bowie), you find a piece of Reed, and another stroll on the wild side. But it’s true—the Velvet Underground, discordant and full of not just musical discord, was rich in talent, vision, rock lyrics that went where no one had dared to go, but could also scare the beejesus out of you while breaking your heart, or in “Baby Jane’s” case, make you dance until you died.

Everybody—outside of Dylan—owed something to Reed: David Byrne, David Bowie, the alt rockers, garage rockers, the big boys in the arena, the little ones in every aspiring 9:30 club joint, the New York too cool kids out all night, and not a few real poets.

What Reed was was a writer of songs, and singing them, he seemed to be a sleep walker, creating in a dream. Go online now and roll through his fugues and songs, and his “Perfect Day” and “Heroin,” the latter approached with caution. Small wonder, his college English professor at Syracuse University was Delmore Schwartz, who was neither easy nor happy-go-lucky, but lyrical as an unpredictable cloud, and in the end, died too young.

He met if not his equal certainly somebody simpatico in Andy Warhol, the two of them could pass for brothers, a different shade of pale. Velvet Underground, which was preceded by pitch-black groups called the Warlocks and the Primitives, rehearsed rehearsed at Warhold’s factory and recorded sometimes with Warholish singer Nico, all strange and blank.

“Baby Jane” and “Rock and Roll” marked a turn: these songs, if you listen to them, reveal rock-and-roll.

Reed’s second wife was Laurie Anderson, herself a sharp rebel and pioneer of new music. Not surprisingly, perhaps, in 2002, he recorded an album centered around the works of Edgar Allan Poe. He also collaborated with Metallica.

Reed had a self-admitted major problem with alcohol, which may or may not have been punctuated by waltzes with heroin. He had had a liver transplant. He was 71 when he died Oct. 27.

In “Sweet Jane,” he sings, “Standing on the corner,/suitcase in my hand/Jack is in his corset, and Jane is hervets/and me/I’m in a rock’n’roll band/Hah!”

“Hah!” Indeed, Mr. Reed.