‘War/Photography’ at the Corcoran Gallery of Art

By • November 7, 2013 0 2546

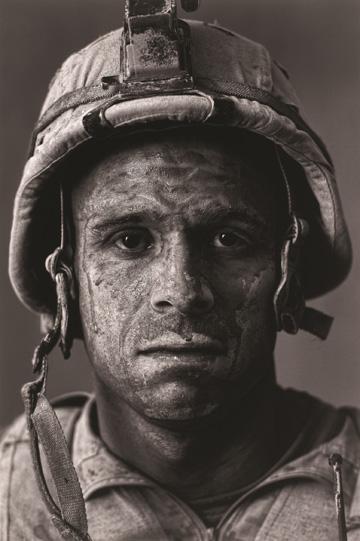

There are pictures of soldiers in “War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath,” whose faces are indelibly distant, hollow and weary. They are faces of otherwise healthy, beautiful men and women whose eyes have gone limp and whose jaws have gone slack, their minds detached from the distress that surrounds them in temporal acts of self preservation. The “thousand-yard stare” of a shell-shocked soldier is surely as old as warfare itself, but not until the invention of photography in the mid-19th century could its stark reality be captured to give a face to the perennial trauma of warfare. Only then did the human cost of war enter the lives of those so far removed from the source of conflict.

Perhaps more so than images of a trench-scarred battlefield, stacks of bodies aligned in a ditch or even the dreadful grandeur of a mushroom cloud: the face of an enervated soldier brings the lasting effects of war to the forefront of our hearts and minds.

In so many ways, “War/Photography,” on view at the Corcoran Gallery of Art through Sept. 29, does just this, confronting its audience with the psychological brutality of war and its lasting physical and cultural ramifications.

To be honest, it is a hard-hitting show. There are many portraits of soldiers with mud-streaked faces looking somewhere beyond the camera’s lens. Others are seen only in silhouette, perceptible by the heavy slump of their shoulders. They are drinking from dirty tin mugs, leaning on the nose of their rifles, resting in trenches, holding frail children.

There are also images of triumph and respite, peace and camaraderie. There are pictures of refugees, fallen soldiers and war-torn streets, as well as memorials and reconstruction efforts. It is a portrait of war that spans 165 years and six continents—from the Mexican-American War through present-day conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, bringing together images by more than 185 photographers from around the world. This is a landmark photographic exhibition, vast in scope and ambition, that shows us the world we live in, how we got here and where we are likely heading.

Walking into the exhibit, viewers are confronted with Robert Clark’s photographic sequence showing the second plane hitting the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001. The four photographs are effectively inert. With the exception of their high quality and resolution, there is nothing visually unusual about them, like a flat tourist snapshot of the New York City skyline from across the Hudson River—except that it shows a Boeing passenger airliner crashing into the World Trade Center, an event that killed almost 3,000 unarmed civilians and instigated of one of history’s longest, deadliest, and most costly wars.

In this articulate plainness, we feel a shock, confusion and panic born from nothing that brings us back to that infamous and fateful day. Like a canvas ripped through the center from within itself, the awe and helplessness of the photographer’s experience comes through—what could he, or anyone, do amidst this instantly monumental devastation? In Clark’s case, he did all he could: he took a picture.

“The Advent of War,” the first chapter of the exhibit’s arc, takes us through this journey. It shows the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, as well as the sinking of the USS Maine off the coast of Cuba in 1898, which led to the Spanish-American War. Both convey with clarity the concept of war’s advent.

The photographs are thus arranged not as a chronological survey, but according to the stages of war: the progression of conflict from acts of instigation to recruitment and training of soldiers, to “the fight” and the fog of war, and to the aftermath of combat, with images showing prisoners and executions, refugees and the wounded, the memorials we construct, and our remembrance.

Part of the exhibit’s success is that it makes no effort at social activism. It is not a cry for peace or an admonition of war’s inevitable devastation. It is a very direct presentation that strives to present facts and context for its images, not its moral parables. With so much contemporary art that wants to point things out and espouse proverbial wisdom—glossary notions of depleting natural resources or the cultural impact of gentrification, for instance—it is incredibly powerful to walk through an exhibit that simply deals with realities head-on, allowing the power of the images to succeed on their own merit. There is no filter to the presentation of the material, and yet it is a body of work that is both profoundly beautiful and deeply impacting. We are immersed in the experience of both soldiers and civilians, prisoners and victors, which enrich our understanding of this momentous subject.

The unhinged gaze of a soldier amidst the chaos of battle is an immeasurably significant contribution to the portrait of modern times, a passing glance filled with profound exhaustion and sorrow. When we talk about war, it is not just history and information we are dealing with, but acts that force us to confront our humanity. And walking out of this taxing exhibit an even stronger feeling emerges: our humanity is worth preserving. To capture it, both at its highest and lowest points, is a sacrifice and a duty that many photographers perform amidst gunfire and civil destruction in order to help us understand our dignity and to bolster the consciousness of future generations.