‘Love in Afghanistan’: a Strong Girl and an American Boy

By • November 18, 2013 0 2502

With “Love in Afghanistan,” playwright Charles Randolph Wright has written a play that covers a lot of bases and touchstone. It’s contemporary, while dealing with centuries-old customs. It’s got the familiar “Romeo and Juliet” and “Madame Butterfly” elements in it. It’s a play about the differences between men and women, Americans and Afghans, love and commitment or love versus commitment.

On the surface or at first glance, “Love in Afghanistan”—at the Cradle at Arena Stage—also appears to have powerful, original characters: Roya, a young Afghan woman, committed to working for her countrywomen, and Sayeed, her sophisticated, urbane and cosmopolitan father, both of them living among the Americans, working as interpreters. Then, there’s Duke, a swaggering, super-charming pop, rap and hip-hop star, here to entertain the troops, and his mother Desiree, a high-power business woman, living in Dubai.

At first, it’s a tale of boy-meets-girl, boy-wants-girl, girl is charmed but resists the American pop star with a keen sense of entitlement. He pushes, she yields, a little, until she finally agrees, pretending to lead him to a man that would act as his guide in a trip to Kabul, which is out of bounds for the visiting super star. The guide is actually Roya, resorting to her habit as a child of dressing up as a boy to get work and help her family, a centuries-old practice called bacha posh.

Stopping for coffee, they almost become the victims of a terrorist bombing, which, since it involved Duke, makes unwanted headlines.

The halting, push-and-pull courtship of Roya, who is dedicated to the cause of Afghan women’s rights has its charms, as does Duke. However, Duke is more about what he wants, than who he wants, going to great lengths to help Roya and her father, including a trip to Dubai where some things that you might expect to happen don’t, and some that you don’t expect do.

In a play that features a pop star and a cultured father in the leads, it’s ironic that the women are the most memorable, appealing characters. They understand each other and protect each other. The men, when push comes to shove, revert to being men. The results of the play’s dramatics tend to diminish the male characters, and there’s a failure to communicate here that doesn’t quite seem believable.

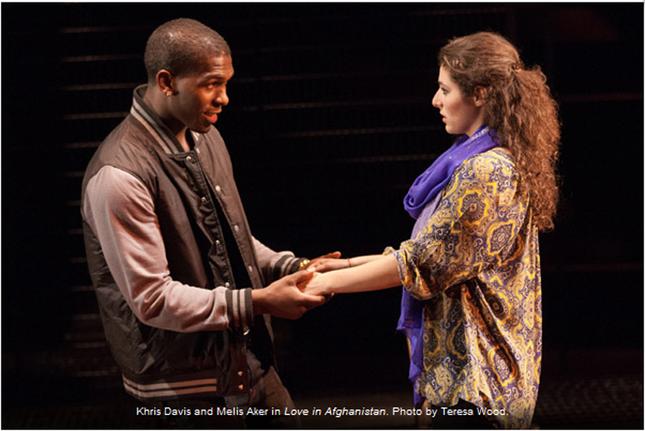

Khris Davis as Duke is all way cool swagger, high energy, a kind of irresistible force that is very resistible when it comes to Roya. She’s obviously a little smitten, and she, in a nod to the irresistible force that is American hip hop and video, is familiar with the young man’s work. Duke, having been raised in the Gold Coast neighborhood of Washington, D.C., is having a hard time with his second album generating street cred. He sees Roya as a kind of object of his determined affection—at best, someone in need of his generosity and help. Oddly, the father concurs in the end.

Old prejudices and habits die hard here and makes the play a kind of halting affair. But not altogether—and that’s thanks to the remarkable actress Melis Aker, who makes Roya an unforgettable character, a strong young woman, aware of the risks, even fearful of them, busy committed to who she is. That kind of commitment may not be apparent to Duke, but Aker makes it real for the audience.