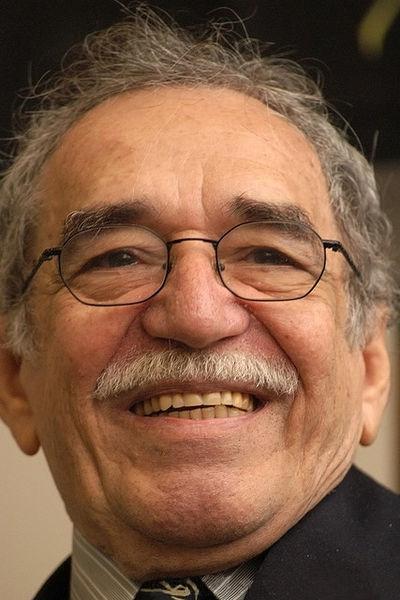

Gabriel Garcia Marquez: Magical, Real Words of Beauty and Life

By • May 1, 2014 0 1766

Gabriel Garcia Marquez passed on last week, leaving behind words and worlds of words and inventions that became books and stories that, if we read seriously and with care and joy, we will keep in our minds for as long as we live or as long as we are able.

He was a Colombian, but he came to personify all the great surging works of Latin American and Spanish-language literature of the latter part of the last century. It was encapsulated into a kind of genre called “magical realism,” of which he was neither the pioneer-inventor nor the lone practitioner, neither in Latin America or in the world. But it might be fair to say that his works brought something unique to the form—the writing was outsized, intoxicating, perfumed with roiling lyricism where reality in the form of sex, politics, and setting bumped up against magic, improbability, music and the whiff of both brimstone and heaven.

He grew up in varying circumstances, and worked in various jobs, and lived in various countries, and traveled and struggled, but, starting as a wordsmith, he ended up a word god in the form of his illustrious novels, “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” “The Autumn of the Patriarch,” “Love in the Time of Cholera,” “The General in His Labyrinth” and “Chronicles of a Death Foretold.”

In 1982, he won the Nobel Prize for literature for “for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts.” His response was a speech called “The Solitude of Latin America.” In truth, he was a Latin American writer, and he was not alone in that, only in the quality and size of his gifts. One thinks of Isabelle Allende from Chile, Carlos Fuentes from Mexico, the Brazilian Jorge Armado.

Marquez and the rest shared the luck and a quality that their translations into English often sounded and read like its true source, which doesn’t happen often in literature—think of Russian novels. They retained their liquidness, their clarity, the smoothness of rolling sentences.

You can get lost in “One Hundred Years of Solitude”—Marquez wasn’t easy—as in a maze and thicket of words as well as in the sheer grandiosity, the ambitions and the music and power of its ideas. It’s a rabbit hole of a book, challenging and not a little frightening, a place where you lose the threads and the memories.

Marquez reportedly suffered from dementia, which makes what he wrote and said all the more affecting: “What matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it” or “It is not true that people stop pursuing dreams because they grow old, they grow old because they stop pursuing dreams.”

“Love in the Time of Cholera” is one of the greatest novels on boy-girl, man-woman, old man-old woman enduring love ever written, in all of its facets, its beating hearts. Every man who has ever felt any sort of heart-stopping, sweat-inducing, ghostly, love will recognize it in this: “To him, she seemed so beautiful, so seductive, so different from ordinary people that he could not understand why no one was as disturbed as he by the clicking of her heels on the paving stones, why no one else’s heart was wild with the breeze stirred by the sighs of her veils, why everyone did not go mad with the movements of her braid, the flight of her hands, the gold of her laughter.”

I wish I’d said or written that sometime in my life.