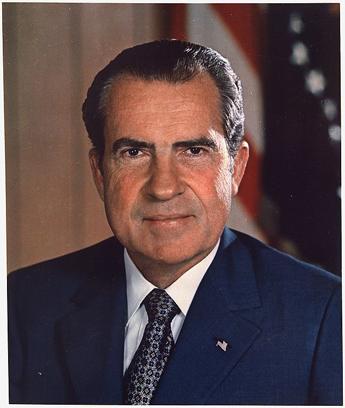

40 Years Ago: When the President Resigned

By • August 11, 2014 0 1889

In Washington, the anniversaries just keep on coming.

“Therefore, I am resigning the office of the Presidency of the United States,” announced President Richard Nixon, embroiled beyond constitutional and legal hope in the Watergate tapes and scandal. No American president had ever uttered those words before. That was Aug. 8, 1974, 40 years ago on Friday. He was gone in helicopter liftoff the following day, Aug. 9, even as Vice President Gerald Ford was sworn in as President of the United States.

Giving voice to a collective national sigh, Ford said, “At last, our long national nightmare is over.”

Well, apparently not. Many people are still dreaming not so good dreams about the Watergate years, with the result there has been a constant flow of books, articles, films, made-for-TV films, documentary and quasi-fictional since Nixon, perhaps the most controversial president in modern times, resigned his office.

There were, of course, numerous tomes by some of the participants and principals, not the least of which was Nixon himself, but also his aides Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, Jeb Magruder, and most and always ever lastingly famous “All The President’s Men” by the Washington Post reporters, who unearthed and covered the scandal, which forever tagged the “gate” on every subsequent political scandal, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

The Post, by going after the story tooth and nail, risking quite a bit before jumping in, and as a consequence solidified its standing as the country’s top newspaper with the New York Times. The Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its Watergate reporting along with legendary political cartoonist Herblock and became something of an institutional celebrity, if there is such a thing.

Nixon, who had won re-election by an unprecedented plus 60-percent margin in 1972, seemed poised on the precipice of great opportunity. Instead, the arrest of several men, who had tried to burglarize the office of the Democratic Party headquarters, located within the Watergate complex, would in not so long a time spiral into revelations of campaign sabotage, bribery, lies, illegal funding, wiretapping and a gigantic coverup that would doom Nixon and most of the ranking members of his administration, and destroy a dramatic political career.

There’s no point today in detailing the story—everyone else has, and in great deal, and continues to do so. Nationally, the highlight was probably Nixon’s emotional resignation speech, and an earlier one in which he had to declare, “I am not a crook.” Top aides and U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell were forced to resign. There were revelations of break-ins, of former CIA agents working for the aptly acronymed CREEP (Campaign to Re-elect the President) and attempts to co-opt an often willing FBI.

Also, there were the tapes, the damnable tapes, thousands of pages of tapes, in which the president, profane, ranting, dispirited, angry and completely uncensored, not only revealed himself to have knowledge of the coverup and all that went with it but displayed a man who was profoundly paranoid, bigoted and vengeful.

The last tape was the last straw—by that time, it was apparent that there were few if any House of Representatives members who weren’t prepared to vote articles of impeachment.

The saga always made for great, eye-popping reading or watching. At least two films of note were made from the material—“Nixon-Frost,” a gripping film made from a gripping stage play, and “Nixon,” starring Anthony Hopkins as a Nixon trapped in a conspiracy as imagined feverishly by Oliver Stone, whose view of American politics (“JFK” and “W”) is nothing if not conspiratorial.

In 2012, there was “Watergate,” a kind of emotional and understated novel by the gifted Thomas Mallon, a political and historical novelist of note (“Henry and Clara” about the couple in the presidential box with Abraham Lincoln and “Dewey Defeats Truman” among others). In “Watergate,” Mallon uses Rosemary Woods and Fred LaRue as major characters and comes up with a work of fiction that is almost a kind of trenchant elegy of and eulogy for the days of Richard Nixon.

John Dean as Nixon’s White House’s counsel was one of the most pivotal figures in the scandal, once called a master manipulator of the cover-up, who also warned the president that there was a cancer on the presidency, close to the presidency.

Dean testified for the prosecution, spent small time in prison and became a prolific author, beginning with his first account of Watergate “Blind Ambition” and, recently, “The Nixon Defense.”

If you want a great sense of what it was like to live in Washington during the Nixon years and especially the Watergate debacle, it’s worth reading and looking at “Washington Journal” by the veteran reporter and graceful writer Elizabeth Drew, who began writing a series of journal entries during the scandal for the New Yorker.

For both facts, and atmospherics, it’s hard to beat this thick (nearly 500 pages) almost day-by-account of the scandal, unfolding like a wave far out to sea, and becoming a tidal wave that engulfed the Nixonites, the city and the country.

I was a reporter in the San Francisco Bay area at the time and was told to take the pulse of the passers-by on the day of the president’s resignation. The reaction amounted to shock, outrage among residents of this very liberal part of California, and confusion about the facts and details of Watergate.

By the time, I moved to Washington, Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman were already in the city, scouting out the scene and the Washington Post for the movie version of “All the President’s Men”.

Nixon was pardoned by President Gerald Ford a year after he resigned. Nixon died in 1994, a sage and wizened member of the New York law establishment. Former presidents extolled Nixon at his funeral as a flawed statesman who had many successes and political talents. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wept at the funeral.

By that time, you could be forgiven if you forgot Nixon’s flaws. “One of Us” was Tom Wicker’s judgement on Nixon in the sense that he suggested that Nixon was made of humble and insecure cloth, much like many Americans, and rose to eminence in spite of the holes in his character.

Those holes, it turns out, remain considerable if you looked at “Nixon by Nixon: In His Own Words,” a documentary by Peter Kunhardt (“Teddy: In His Own Words”), in a style that unfilters Nixon amid not only Watergate but also his own biggest triumph, the trip to China. With clips on different subjects—tapes, the press, China, Viet Nam—Kunhardt references Nixon through his recorded voice from the infamous tapes talking with aides like Ken H. R. Haldeman or Chuck Colson. The outpouring remains shocking—just when you think you’ve forgotten this as ancient history—there he is bristling with vitriol, about Jews—they’re “disloyal,” full of bigoted cliches and characterizations of minorities—and a burning hatred of the press. At one point, he’s making out a media list for the trip to China “the networks, sure, the wires and only a couple of others. Nothing for Post or the Times. Screw them. Not even photographers.”

His voice, then, becomes as alive as you or I, because we know this to be the truth. The unvarnished truth.

History may judge Nixon as a great president, if we are to believe Kissinger. After all, he was the first president to go to China. He was also the first president to resign his office.

History will remember that, too.