El Greco: Transcending the Renaissance

By • February 6, 2015 0 2580

El Greco was foremost an artist of the Spanish Renaissance, whose painted icons are among the most recognizable works in all of art history. With even the slightest familiarity of the artist’s work, his paintings become as instantly attributable as a Jackson Pollock. Not much work of the 16th century survives in the realm of intellectual pop culture, yet El Greco endured centuries of obscurity to achieve a sudden transcendence in the early 20th century, and his legacy seems all but fated for the ages.

For sake of candor, I will not feign any deeper knowledge of Renaissance art than a vague canonical familiarity with the masters—certainly no more than a middling history buff. In El Greco’s era, all subject matter in art was effectively predetermined, relegated by church and the nobility to biblical scenes, portraiture and what amounts to political propaganda. So the real issue of El Greco in our time is not what he painted, but how he painted—not what his work showed, but what it revealed. What brought this work suddenly into the limelight some 300 years later, and why are their impressions so deeply affecting and seemingly permanent?

At the National Gallery through February 16, a 400th anniversary celebration of El Greco features ten works by the groundbreaking genius of figure painting, which offers a rare opportunity to see the accumulation, breadth and development of his career.

Domenikos Theotokopoulos (1541 – 1614), universally known as El Greco, was born on the Greek island of Crete, where he achieved mastery as a painter of Byzantine icons by age 26. Moving to Venice, he absorbed the lessons of High Renaissance masters, notably Titian and Tintoretto, before departing for Rome in 1570. There, he studied the work of Michelangelo and encountered the style known as mannerism, which rejected the logic and naturalism of Renaissance art. He relocated to Spain in 1576 and spent the rest of his life in Toledo, where he finally received the major commissions that had eluded him in Italy. Unlike the Italian mannerists, who aimed at elegant artifice, El Greco used their dramatically elongated figures and ambiguous treatment of space for expressive ends. Integrating these diverse influences, he developed a unique style that, from a historical perspective, captures the religious fervor of Counter-Reformation Spain.

But this is not what attracted artists like, Cezanne, Degas, Modigliani, Picasso, Giacometti, and so many others well throughout the 20th century, who ensured El Greco’s place in history. I would suggest that it was his figural obsession which, though couched in biblical allusion, exists almost unfettered by religious fervor. This resonated with the agnostic spirituality of turn-of-the-century artistic innovation, as well as its defiance of narrative conventions.

In paintings like “Saint Ildefonso,” “The Repentant Saint Peter,” and especially “Saint Jerome,” there is a physical agony to the figures, as the bodies crane and twist as if sculpted from crude clay. They contain a strong sense of yearning, doubt, distortion and chaos that found its id among the industrial age, and again amidst the new social consciousness brought about by Einstein’s age of relativity.

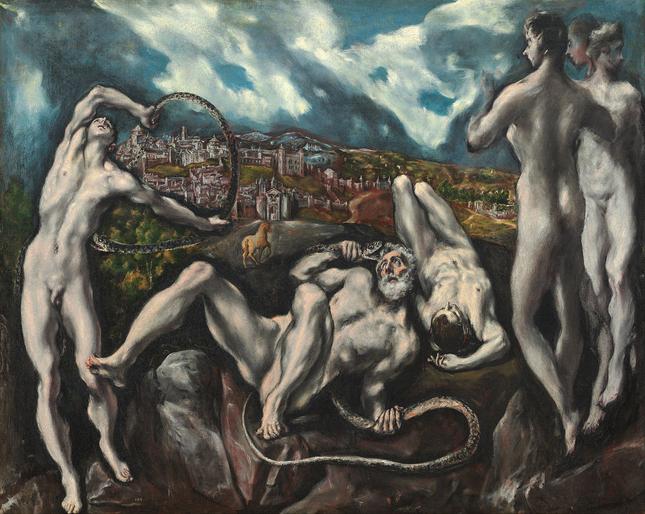

The painting, “Laocoön,” is strangely a modern masterpiece, painted three centuries too soon. The figures pose dramatically in a relaxed state of heightened physicality, like Degas’ dancers, and float in narrative and moral ambiguity, like Picasso’s “Family of Saltimbanques.” In a mere impression of a horse and clouds in the background, many brush strokes exist on their own terms, defining nothing but the space of the canvas. It is hardly abstraction, but it is certainly a broad step away from reality and into the realm of painterly suggestion.

Not much work from the 16th century can be absorbed purely on its own terms, in the way that art of the last 150 years strives for self-actualization and is made to be understood for its own sake (which is itself but a reflection of our intellectual era). El Greco was perhaps the first artist to recognize his medium as its own religion. He was an innovator of expression in light, the human figure, and paint itself. His work conveys deep spirituality, like the Byzantine icons of his youth, but they are independently alive in their sheer force of expression.

Perhaps El Greco’s rediscovery in the late 19th century was no more than a fluke, but it may just be that the Gods of paint rescued him from a long trial in purgatory. At the very least, he is most deserving of our time and consideration, and the paintings remain beautiful.

El Greco in the National Gallery of Art and Washington-Area Collections: A 400th Anniversary Celebration, is on view at the National Gallery of Art through February 16. For more information visit www.nga.gov