Changing the Eyes of the World: ‘Van Gogh Repetitions’ at the Phillips Collection

By • February 8, 2015 0 2812

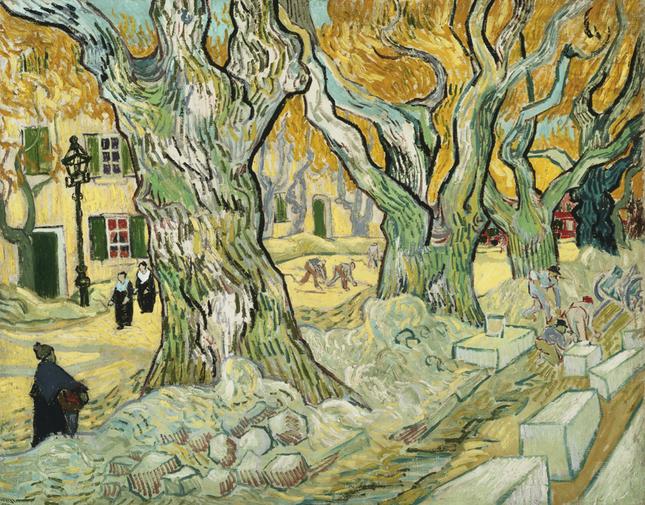

Vincent van Gogh was a desperate and lonely genius, so the story goes. He had a compulsion visible in all his paintings, thickly built up with coarse and blocky brushwork that layered in hundreds of individually visible strokes, which alludes to an artist both besot by his subject matter and incredibly frustrated with his own interpretations of them. It is an anguish of morbid intrigue, a conflicting lust and discontent for all matters of life and art that points to van Gogh’s calamitous and fabled end. The images he made are so recognizable and his life so notorious that we sometimes forget how awfully damn good of a painter he happened to be.

In its surprisingly modest but scrupulous exhibit, “Van Gogh Repetitions,” the Phillips Collection strives to bring the focus of van Gogh back to his artwork, exploring his painting techniques and habits, whereby he reworked compositions and subjects with a fiery discipline to craft his indelible images. Audiences are privileged to observe how van Gogh borrowed from (and often outright copied) artists he admired, from Paul Gauguin to Jean-Francois Millet, and how he returned time and again to the people and places that so inspired him in order to pursue the rendering of not just their shape and character, but of their essence. Ultimately, we are enabled to judge his paintings on their individual merit, stripped clean of their often-overpowering cultural influence, which only makes us see him again, and for the first time, as the groundbreaking visionary that taught us to see the world in a new light.

In today’s era of third-generation visual glut, it is easy to forget how innovative van Gogh’s style really was; what he saw and put down on canvas was unprecedented. His tendency to over-saturate colors, for instance, with sun-flecked yellow fields and waxy, pulsing blue skies, is something we now readily take for granted. Instagram photo filters owe a lot to the sensibility of van Gogh’s color palette, in a way—anyone can now make an ordinary picture look good by blowing out its colors through preprogrammed filters, all of which end up looking a little bit brighter and richer than what was perhaps ever there in the first place. Van Gogh saw these colors in his mind, and maybe this is his legacy: he taught us to adore and romanticize what has always been there, just so long as we strive to see beyond its surface.

His paintings stand out so well in our cultural consciousness because his paintings are almost memories in themselves, distilled and concentrated explosions of color, light, people and places, that follow a unique visual language at once fresh and familiar. Just the mention of a van Gogh wheat field brings a myriad of images bubbling to the surface. His paintings are, in a word, laconic, like a worthy truism of which we remember its inherent wisdom even if we cannot recall its precise form.

Many of the artist’s most famous works are missing from the exhibit (The Starry Night, Café Terrace at Night, and any self portraits or floral paintings), which opts instead to display lesser known portraits and landscapes. This does not mean that you won’t recognize most of the paintings, and a number of his more famous works indeed made it onto the walls, notably a portrait of his obtusely angled bedroom in Arles in the south of France where he stayed during the summer of 1888. There he was influenced by the strong coastal sunlight, and his work grew brighter in color as he developed his singular and highly recognizable style.

There are multiple canvases devoted to single subjects in the exhibit, which ultimately serves to refocus attention on van Gogh the painter (instead of the cultural icon), and allow an appraisal of his work with fresh eyes. The point herein is not necessarily to judge which of the three is the best version of, say, The Postman Joseph Roulin—a close friend that van Gogh greatly admired—but to watch how van Gogh continually rediscovered and redeveloped his subjects. It is an act of stamina, and one by which many 20th century artists took a lesson. Think of Giacometti’s innumerable portrait busts of his brother Diego, or Willem de Kooning’s Woman series. All these paintings are strong on their own, but seeing them together is like witnessing a religious ritual.

That van Gogh became one of the world’s preeminent artists is indisputable. How he achieved this is less considered, typically passed off as some myth of a beautifully demented mind. But his many studies exhibited in Van Gogh Repetitions point to an artist with exceptional deliberation and methodical attention to detail. Van Gogh’s effortless genius, it seems, came from rigorous and deeply considered observational innovation. It changed our visual lexicon and helped us rediscover the beauty in all that surrounds us, from an aging woman or a grove of poplars, to a vase full of dried up sunflowers.

If there is ever an exhibit of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings in Washington, anyone would be remiss not to see it. With this exhibit in particular, it is a unique opportunity to see what it takes to change the eyes of the world.

“Van Gogh Repetitions” is on view at the Phillips Collection through Jan. 26. For more information, visit www.PhillipsCollection.org