‘Lights Rise on Grace’ Brings Love Triangle, Real World Drama to Woolly Mammoth

By • May 11, 2015 0 1617

It’s been 35 years since Woolly Mammoth Theatre began its Washington theatrical adventure and journey. Looking at this season’s offerings, and especially the current production of playwright Chad Beckim’s “Lights Rise on Grace,” it seems like yesterday.

The play—poetic, crude, raw and wholly imaginative—is what audiences might call a “Woolly” play, even though it had its beginning as a New York Fringe Festival entry. It seems carved out of the time of now, it’s unlike anything you’re quite likely to see here (no disrespect to other companies meant), it’s beautifully acted and totally engaging. The faces—three remarkably gifted actors—are new, and so is the spirit of the play and its structure, which seem beyond category.

It’s not that we don’t see new plays in Washington these days, staged by familiar companies and groups as well as new ones with attitude and style. It’s that new plays, new writers, new artists, has been a Woolly trademark under Artistic Director Howard Shalwitz for all these years that a play like “Lights Rise on Grace” is part of an ongoing and singular achievement—even though it’s now in permanent downtown digs, Woolly continues to dance on the sharp edge of edgy with every offering.

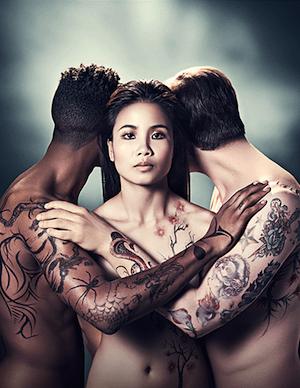

“Lights Rise on Grace” is a particularly daunting, and moving example of that tradition. It concerns a kind of unusual love triangle that plays itself out in a tough and layered urban environment of neighborhood and school, not to mention prison. It sees Grace, a shy, but eager-for-experience daughter of strict Chinese immigrants meeting an affable, charismatic, “can’t help loving him” African American boy in school, who greets her with by saying, “I want to know you”, clearly meaning both senses of the phrase. His name is Large—named for his size at birth, not for anything else—and the two fall deeply, it seems, and passionately, and very physically in love, in spite of disapprovals from their peers and families.

And then, Large disappears for a long time—into prison, as it turns out, for an assault. Grace doesn’t know why, she just known that young man who filled up her live and soul is gone without reason. In prison, Large meets and eventually is protected by and gets intimate with a white prisoner named Riece. Eventually, Large gets out of prison and is reunited with Grace, who has left her home, made a life for herself, and is both astonished and in total turmoil of the return of her one and only love, if not lover.

Riece soon follows, and the three begin a sort of awkward, confusing, tense relationship, pushing toward a kind of family. But Large is not the same—prison has changed and damaged his natural optimism and charm, and his assurance about his place in the world and who he is. Grace, too, is confused by the new Large whom she’s longed for. Adding to the confusion, but also providing a kind of solid steadiness, is the presence of Riece, especially after Grace becomes pregnant.

Things don’t tidy up—they become more confusing for the audience and characters as well as they try to do the right things for themselves and each other, faced with difficult decisions.

They occupy a space for themselves in a rich and rough environment, physical, cultural and emotional. This is an urban and changing world of neighborhoods—much like that world is changing in the city, in this case where generations maul each other pitilessly, where violence is abundant and, economically and identity-wise, life is a grind where love, and a paying job are difficult to achieve.

The stark, prison-like set is a kind of metaphor not just for incarceration but for life itself — or at least their particular lives, which echo strongly here.

The actors are (relatively) new to Washington, although Ryan Barry (Riece), has workshopped the play in New York, where it was directed by Robert O’Hara, who is directing Woolly’s next production, “America Zombie.” “Grace” is directed here by Michael John Garces, who is the artistic director of Cornerstone Theater Company in Los Angeles and is a company member of Woolly where he directed three powerful and difficult plays, “We Are Proud to Present…” by Jackie Sibblies Drury,” “The Convert” by Danai Gurina and “Oedipus el Rey” by Luis Alfar. If “Lights Rise on Grace” resembles any of the three, it is “Oedipus,” which also had a stark, crackling urban air to it in taking the Greek classic to the barrio.

“Grace” is almost elliptic in the way it tells the story, which is always open-ended—characters turn to the audience to tell the story, their point of view, an effective and intimate approach, especially when Jeena Yi, as Grace, opens the play with an almost verbally naked telling of how she met and loved Large, lost him, and then embarked on a series of almost brutal sexual encounters in the aftermath.

Yi, the hugely appealing DeLance Minefee as Large, and a quietly effective Ryan Barry as Riece, seem the best kind of actors: they’re naturals, inhabiting their characters fully, while also playing the parts of Chinese parents and relatives, Large’s street and school peers, inmates and prison folk.

In these days of instant communication and entertainment gratification, I haven’t seen a play in a very long time that so stilled the audience into silent attention. I think there are acts of recognition here—these are characters that live in a changing world, where attitudes about sex, gender, race and multi-ethnicity are shifting rapidly.

Beckim, who describes himself as growing up as a white kid with a preference for African American culture, is a gifted writer. Even in the realistic attitudes on stage, he finds a way to make poetic observations and gives his characters a generosity they both deserve and need.

“Lights Rising on Grace” runs through April 26 at Woolly Mammoth.