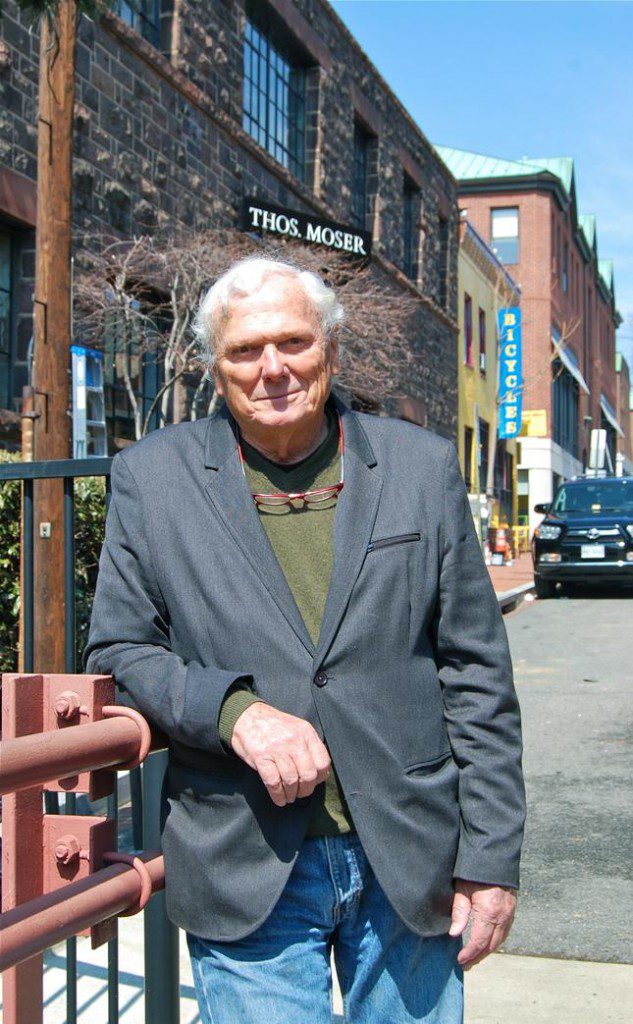

Tom Moser, Maine’s Wizard of Wood

By • May 11, 2015 0 3109

“We give a second life to trees,” said Thomas Moser, founder of Thos. Moser Handmade American Furniture, whose company seems to treat every day as if it were Earth Day.

Celebrating his 80th birthday, Moser was at the opening of the company’s new store in Georgetown March 20 to say hello to Maine’s Congressional delegation and his clients and fans – and, we might add, to charm anyone talking with him.

The company’s chairs, tables and dressers of simple, timeless design are highly regarded, expensive, meant to last generations. Moser gets the attention of architects, designers and homeowners, as well as schools and libraries, even presidential ones.

Handcrafted and signed, company output is 85-percent residential. One Maryland house reportedly has more than 30 pieces. Moser has furnished parts of Georgetown University’s law library as well as that of Catholic University. The company’s products are on full display at the Park Hyatt on M Street in the West End and in its Blue Duck Tavern.

Aaron Moser, one of the founder’s sons, heads the company’s contract division, which serves offices and schools. He is as proud of the company’s 55 pieces at the George W. Bush Presidential Library as he is of Moser’s relationship with St. Timothy’s School, just outside Baltimore, and its students, who attend woodworking classes at the Maine factory.

“We’re not furniture purveyors,” the company founder says. “We’re craftsman.” His enthusiasm is infectious, and his brutal honesty and cheeriness fill a room.

The new Georgetown store on 33rd Street is “more like an art gallery,” the company’s “finest in the country,” Moser said, looking around the 5,000-square-foot space. Located a few doors north at the corner of 33rd and M Streets for 10 years, the Moser store is back after almost a three-year absence because Georgetown fits the company’s marketing demographics perfectly.

It is a little out of the way for Moser – the C&O Canal is down the street – but he loves its ambiance and is curious about the history of the building at 1028 33rd St. NW.

The building’s solid stone (from the Aqueduct Bridge which was replaced by Key Bridge in 1923) and brickwork lines up well with a Moser mantra, a reworded Shakerism: “Build an object as though it were to last a thousand years and as if you were to die tomorrow.”

“I learned woodworking from dead people,” said Moser, not skipping a beat in retelling how he became part of the handicraft revival of the 1970s.

Originally from Chicago, an Air Force veteran, he was a college professor teaching language and speech pathology. He taught in Saudi Arabia for a few years, setting up language labs at the College of Petroleum and Minerals.

After years of pursuing woodworking as a hobby – beginning with antique-hunting and making missing drawers for pieces: “We bought 26 grandfather clocks in parts.” He called the learning process a case of reverse engineering. “Parts of things show continuity.”

Soon enough, Moser was all in, starting his business in 1972 in New Gloucester, Maine, which, as of 2010, still holds a Shaker community of four. With his wife Mary’s support – they met when he was 14 years old and she was 12 – a career reinvention from academic to woodworker took place. Married for 58 years, the couple has four sons: Matthew, Andrew, Aaron and David.

“I wanted to recapture the craft of the early-19th-century artisans,” Moser said. “I venerate the 19th century.” He liked what Americans produced before factories began to dot the nation in the second half of the 1800s. He said he is “fascinated by Shaker design, the honesty of material, the economy of labor. The Shakers prayed to God with their hands.”

Other influences on Moser include Stickley, the Arts and Crafts movement and Bauhaus design. “My work is derivative,” he said. As for the classic Windsor chair, “the best ones are in America.”

“We are the antithesis of Ikea,” says Moser CEO Bill McGonagle. “We like to say our furniture lasts as long as the time it took the tree to grow.” He joined the company in 2012 after working for another Maine Tom: natural products maker Tom’s of Maine.

As for the Moser company’s environmental soundness, McGonagle noted, “We have a small footprint.” There are about 200 employees.

“It’s how we source the wood,” which grows no more than 600 miles from the factory and office in Auburn, Maine, he said. “We don’t throw any wood away. We use half of what we buy. The remainder craftsmen buy for their art. Scraps move on to being firewood or sawdust used as bedding.”

The company uses domestic hardwoods only: no teak, no mahogany.

And Moser’s favorite kind of wood? “Cherry,” he said. “It reveals what God put there.”