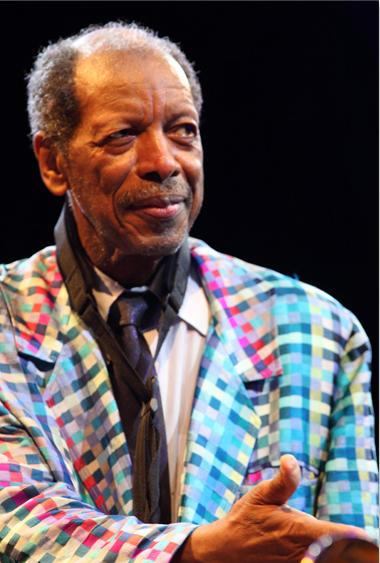

Free Jazzer Ornette Coleman (1930-2015)

By • July 16, 2015 0 1668

The 11th D.C. Jazz Festival ended Tuesday in an expansive stretch of concerts all over the bustling Washington landscape, stretching boundaries, embracing new genres, serving youth — with occasional backward glances at this most American of musical forms.

Somewhere in the middle of all this, on June 11, Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman died at the age of 85. Coleman was a jazz giant from the past who was also always about its future. Once you start reading about him, and listening to some of his particularly free and flowing music (on You Tube, if not elsewhere), you get lost in his story and his music.

Coming out of Texas, he aim was to set jazz free, blowing the alto sax, composing, arranging, playing most often with his jazz family of cornetist Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden, drummer Billy Higgins and others, including pianist Paul Bley. Sometimes he played with his son Dernardo on drums. He also played the trumpet and the violin.

He was — once he knew what he was, which was, as described in many a headline, a “jazzman” — always pushing, looking ahead in the same way that Charlie Parker was, rearranging the whole damn thing. Hence, and soon enough, in 1959, came “Tomorrow is the Question!” — a boppy, beyond-boppy and singular composition that posited an answer to the question of “What Is To Be Done?” The answer: “The Shape of Jazz to Come.”

This seems immodest, but it was also true. Critics called it avant garde, as they would some of Miles Davis’s work.

Coleman’s music was a strange kind of avant garde. It had melodic spurts, sweet stuff and blues and rambling, rumbling moments of sax and horn. It could be mistaken for another version of Americana, deeper and more wounding while optimistic. His music was often controversial: praised by the likes of Leonard Bernstein, but not so much by Davis himself, who called him “all screwed up inside.”

No matter how far you stretch jazz or decompress it, or bastardize it or marry and fuse it to something else, it always brings with it its favorite child, improvisation. That’s the genius of jazz, that’s how you bend it and blend it at the same time. Jazz without improvisation (for a minute or twenty) is really jazz without its soul, if not its heart. Coleman understood that, which is not to say that he wanted the music to change to the point that nobody understood it, or worse, wanted to listen to it.

You get a sense of where the train went off the tracks into the future in “Free Jazz.” One player called it organized chaos.

But it’s also the kind of thing you’re still likely to hear on a given night in some drifty club, a quartet, the sax going on off, out of bounds, getting joined in disjointed fashion by a horn, drums coming on soft, then in a fury, and bass catching up, drifting off, coming right on in. If there’s a piano, well, something different.

It’s a funny thing, this envelope pushing. Stick around long enough, and everybody recognizes who you are at last, and that you’ve touched everyone. The obituary in Rolling Stone by David Fricke, for instance — called “Ornette Coleman: The Man Who Set Jazz Free” — recalled a story about Jerry Garcia playing on Coleman’s album “Virgin Beauty,” the point being that Coleman, like Parker, influenced everybody, everywhere.

On You Tube, the music gives you an idea of a journey: “Free Jazz,” the classic “Lonely Woman,” “Bebop with Hard Bop,” “Skies of America,” which one critic said Virgil Thompson would have been proud of. The tributes in the comments came in American, in Japanese, in German, Arabic, French and Spanish, rest in peace and swing.

Coleman’s spirit lives in every new note, and every old one too. The jazzman is home.