Irving Penn at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

By • November 5, 2015 0 1610

In preparing to write a piece on a new exhibition, I often sit down with the catalogue after my visit and bookmark certain pages with cut-up bits of paper, on which I write little notes and reminders to myself. If someone were to stumble upon one of these marked-up catalogues, seeing it stuffed full of paper shreds with scribbled words — “Victor Hugo,” “divine bones,” “gothic horror!” — they might well believe its owner to have been a mild schizophrenic.

But if someone found my latest catalogue, from the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s “Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty” (on view through March 20), they?d be staring down the barrel of something more akin to an art student?s nervous breakdown.

Irving Penn is one of the most iconic photographers of our time. Both a commercial and arthouse sensation throughout a greater portion of the 20th century, he is among the rare breed of artists who successfully survived for his entire career in the narrow, highly combustible space between mainstream and critical popularity.

Penn began as an art student in 1930s Philadelphia. After working as a freelance designer, he did a brief stint in 1940 as the artistic director of Saks Fifth Avenue, before dropping it all to spend a year traveling and taking photographs around the United States and Mexico (some of these shots are included in this exhibition).

Returning to New York, Penn took a design position with Vogue magazine, where his director suggested he try working with photography. His first cover shot for Vogue hit the stands in October 1943. Penn was not quite 26 years old.

Over the next sixty years, Penn took some of the most unforgettable photos of our time, with a meticulous eye that redefined and obliterated the perceived limitations of photography as art. He ran the gamut of fashion photography, commercial and advertorial work, portraiture, photojournalism, formal studies of still lives and Romanesque nudes, and the lid-popping delirium of avant-garde experimentation.

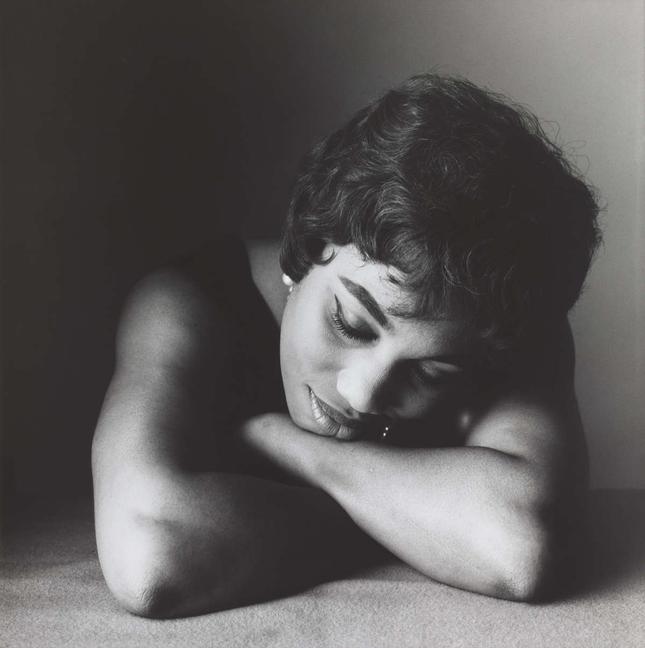

He composed and lit every subject with equally compulsive attention, from Truman Capote and Alberto Giacometti to used cigarette butts that he had his assistants pick up off the street. He played with chemicals and exposures in the darkroom the way a painter experiments with glazing mediums, extenders and stabilizers. His tones were rich and warm, and his manipulation of light and atmosphere bore such lush and striking contrast that his subjects seem to flower from seeds of darkness.

As fine as his technique was, however, this isn?t what made Penn?s work so beloved and admired (any more than Picasso is remembered for his brushstrokes). There are a lot of technically talented photographers in the world. It is the spirit of what he captured through his lens, the ineffable artistic matter of both beauty and relevance, that left such an indelible mark across the ether of American iconography.

I suppose it is this that I am expected to decipher as a writer and an observer of fine art, but frankly I?m not sure that I can. So many artists attempt to do exactly what he did and fall short. To make work that is emotionally charged, aesthetically fresh, innovative and transfixing is a colossal achievement. To do it for over half a century is nearly supernatural.

Penn could maneuver so deftly through such vast stylistic ranges it is mindboggling. In some cases, his still life studies — stacked marrow bones and steel blocks — are as buttery, geometric and tonally delicate as those painted by Giorgio Morandi. In others, such as in “Composition with Pitcher and Eau de Cologne” of 1979, they take on the overwrought bounty of 17th-century Dutch still-life traditions.

His studies of muddy gloves and cigarette boxes buzz with the textural amplitude of Chuck Close’s immense portraiture. His own portraits, however, range in style from nightmarish surrealism (“Two Rissani Women in Black with Bread”) to formal (his portrait of Giacometti is a master class in value study) to Winogrand-like cultural snapshots and smoky, dreamlike odes to women and haute couture (fashion has never looked better than through his lens).

If there is a shortcoming to Penn?s work, it is clear that he was better in a controlled studio setting, over which he could exercise his aesthetic governance, than the uncooperative, disorderly environment of the outside world. The few images within the exhibition of urban street scenes and natural environments — all of them from very early in his career — are oddly disconnected from their subjects.

There is a mystifying painterly essence to his photographs. Your eyes traverse his terrains of texture, gradation and tone not like a typical photographic image — where you seek to gather the necessary informational content of “what is it?” — but with the nervous curiosity of a painted abstraction, for which we have trained our minds to seize esoteric intellectual feelings as literally as physical ballasts.

In a nutshell, this is why my brain blew an art fuse. Not that I mind. In fact, it?s one of the greatest meltdowns I?ve ever experienced.