Scalia’s Passing Felt Beyond the Supreme Court

By • March 7, 2016 0 1361

The death of Associate Justice Antonin Scalia on Feb. 13 has shaken political Washington as it ponders what comes next for the Supreme Court—and the nation—just as it recounts its stories about Scalia and his colleagues and friends that worrying sense of continued lost civility between idealogical opponents we face today.

The most compelling story is that of the friendship between Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the long-serving justice whom she called one of her “best buddies” in her statement on Sunday, Feb. 14, Valentine’s Day.

Ginsburg wrote: “He was a jurist of captivating brilliance and wit, with a rare talent to make even the most sober judge laugh. The press referred to his ‘energetic fervor,’ ‘astringent intellect,’ ‘peppery prose,’ ‘acumen,’ and ‘affability,’ all apt descriptions. He was eminently quotable, his pungent opinions so clearly stated that his words never slipped from the reader’s grasp.

“Justice Scalia once described as the peak of his days on the bench an evening at the Opera Ball when he joined two Washington National Opera tenors at the piano for a medley of songs. He called it the famous Three Tenors performance. He was, indeed, a magnificent performer. It was my great good fortune to have known him as working colleague and treasured friend.”

It is curious to take note that “Scalia/Ginsburg,” an American comic opera by Derrick Wang made its debut last July at Lorin Maazel’s Castleton Festival in Virginia. Promoters stressed the one-act opera was about “law, music and the power of friendship in a divided world,” while adding, “Justice will be sung.”

In March 2015, Scalia himself was portrayed by Shakespearean actor Edward Gero in the Arena Stage production of “The Originalist.” Indeed, playing now at Arena is “The City of Conversation,” a drama centered around the failed nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court. If not pleased with some of the rhetoric, Scalia would no doubt be pleased with the theatrics.

Scalia was born in 1936 in Trenton, N.J., and moved to Queen, N.Y., attending public school before entering Manhattan’s premier Jesuit Xavier High School, graduating first in his class and went to the nation’s capital, attending Georgetown University, America’s oldest Catholic and Jesuit institution of higher learning. He was a debater in its Philodemic Society, an actor in student plays and the valedictorian of the class of 1957. He went on to Harvard Law School and was later a law professor at the University of Virginia. President Ronald Reagan nominated Scalia for the Supreme Court, where he began his work on Sept. 26, 1986.

Washington became his town but he travelled the world, whether seen with his friend Ginsburg in India and just a few weeks ago in Singapore with a writing colleague. Even the manager at al Tiramisu restaurant, where Scalia was a frequent diner, had something to say about the 79-year-old judge.

“Scalia’s greatest strength, his steadfastness, was also his greatest weakness” was the headline for an opinion in the Washington Post by legal expert Jonathan Turley, a law professor at George Washington University.

Turley offered a telling summary of Scalia: “Like Louis Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes, he was a ‘great dissenter’ who refused to compromise on his core beliefs. He was entirely comfortable being a dissent of one. And he was greatly discomfited by the idea of exchanging principle for some plurality of votes on a decision. . . .

“Ironically, Scalia’s passing comes at a time when the public is craving precisely the type of authenticity that he personified. The rejection of establishment candidates in both the Republican and Democratic races reflects this desire for leaders who are not beholden to others and unyielding in their principles. That was Nino Scalia. Love him or hate him, he was the genuine article. . . .

“Scalia clearly relished a debate and often seemed to court controversy. It was a tendency familiar for anyone who grew up in a large Italian family: If you really cared for others, you argued with passion. Fights around the table were a sign of love and respect. Perhaps it was this upbringing that made it so hard for Scalia to resist a good argument inside or outside the court. He sometimes spoke on issues involved in cases coming before him, which was ill-advised. He was the arguably first celebrity justice. . . .

“Scalia resisted the legal indeterminacy and intellectual dishonesty that he saw as a corruption of modern constitutional analysis. He believed that the law was not something that should be moved for convenience or popularity. Neither was he. He finished in the very same place he began in 1986. In the end, he is one of the few justices who can claim that he changed the Supreme Court more than the court changed him.”

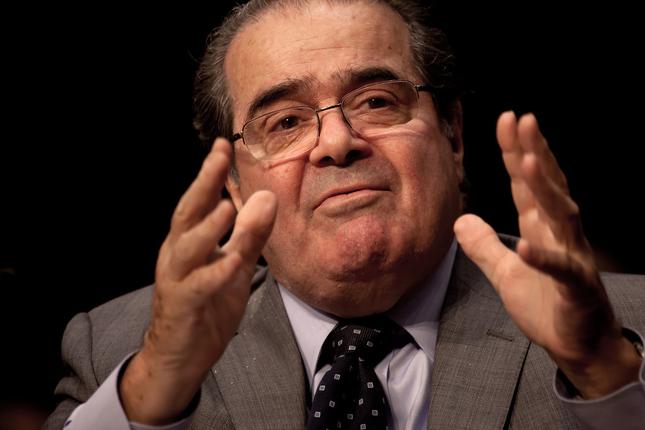

- Justice Antonin Scalia. | Jeff Malet