A Sanctuary for Apparitions, in Bronze

By • March 18, 2016 0 1818

There is something exceptionally and uniquely satisfying about seeing ancient sculpture.

Since the idea of “l’art pour l’art” took hold in the 19th century, the art-going public has been fed a steadily increasing diet of what is conceitedly called “autotelic” art: Art that exists with intrinsic value, serving no greater political, religious or didactic functions.

This principle laid the groundwork for a new era of art and artists, from Monet to Picasso to Pollock and from Impressionism to Cubism to the atomic crack of pure abstraction.

For all that it can be exalted or demonized for its lasting influence on the history of art, one of the truly great effects of this powerful idea was that it taught the world to look always with fresh eyes and to perpetually reconsider the nature of beauty. This has opened the doors to a wider, more dynamic and inclusive appreciation for art.

So when confronted with a 2,300-year-old bronze sculpture, a richly cultivated history comes together with a beauty so inherent and incomparable that the result is something like the absolute museum experience.

At the National Gallery of Art through March 31, “Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World” offers this experience, bringing together 50 of the greatest remaining bronzes from a monumental period of Western history.

The Hellenistic era was a wildly fertile period for the development of art and literature, beginning around 330 B.C. with the conquests of Alexander the Great and ending in 31 B.C. with the rise of Augustus Caesar and the Roman Empire over Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

Within these three centuries, the art of bronze casting drove artistic innovation in Greece and across the Mediterranean. Surpassing marble with its tensile strength, reflective surfaces and ability to capture fine detail, bronze statues were produced in the thousands throughout the Hellenistic world.

Of the countless bronzes that once adorned Hellenistic cities, fewer than 200 are known today, many of them just fragments. This gives a false impression today that ancient sculpture was mainly of marble. As bronze is a recyclable and valuable commodity, most of the sculptures were melted down after the fall of the empire to make coins or weapons or for other commercial uses.

Others corroded, and still more were lost to shipwrecks. (There are unknowable quantities of bronzes sitting at the bottom of the Mediterranean; several works in this exhibition were chanced upon by fishermen.) So it is a rare case that a bronze sculpture survived.

But if you knew nothing of the remarkable and unlikely history that put the works before you, the sculptures would still send tingles through your spine.

As they are cast from models of wax or clay, bronze sculptures can capture a startling delicacy of features and emotion. Hair is wistful, lips pout gently, brows furrow and torsos twist in controlled motion.

There is a mythical quality about their collective presence as they stand over you, looking toward an imaginary horizon in unknowable preoccupation. And the fractured, mottled, porous ancient metal of which the faces and bodies are composed hides among its cavities and cankers the most delicate, nuanced representations of human emotion ever rendered. The galleries are thus transformed into a sanctuary for apparitions.

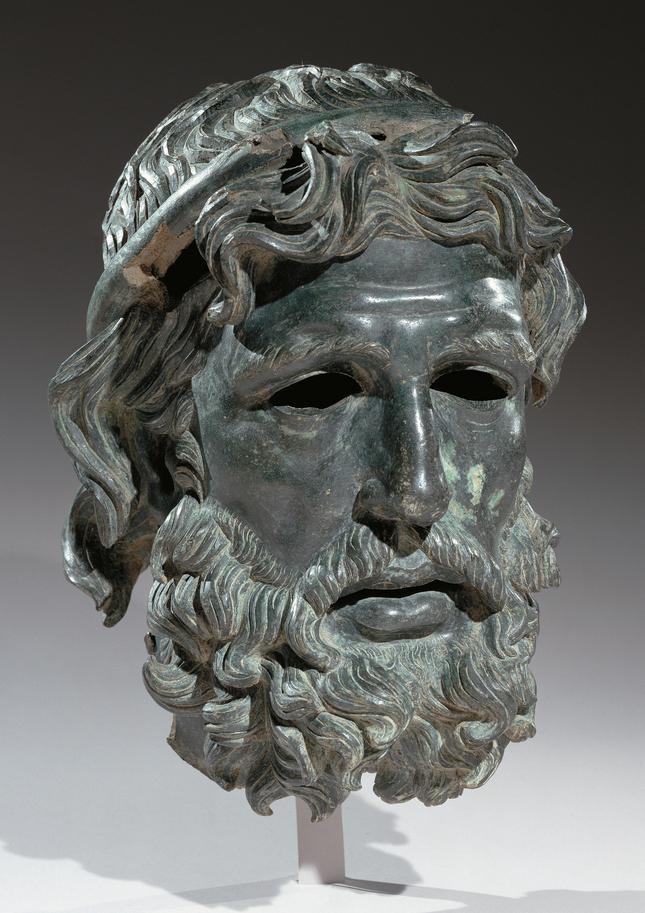

In “Head of a God or Poet,” from the first century B.C., there is an unshakeable sorrow that emanates from the sunken cheeks and hangdog eyes, framed by a billowing beard and windswept hair. It feels pointedly like loss, in the same way you would recognize it in a stranger’s face on the street.

“Athlete,” from the first century A.D., is just overwhelming, a perfect intersection of history and unadulterated beauty. Pieced together after having been shattered, the quilt-patch surface of the figure, as it refracts subtly against the light, corresponds to the rolling planes of its body, marrying organic curves with a subtle geometric fracturing.

The National Gallery does a fine job contextualizing the work, creating atmospheric environments by displaying original sculpture pedestals and hanging large-scale reproductions of wall paintings from Pompeii behind some of the works.

As the gallery walls will tell you, this exhibition is an unprecedented opportunity to appreciate bronze in antiquity and the innovations of Hellenistic sculptors. It also offers an elusive encounter between abstract beauty and stunning realism, unveiling universal threads of fragile emotion that forge personal connections with individual people that have been dead for over two millennia. It is a stirring, strange and transcendent experience.

- “Head of a God or Poet,” 100-1 B.C. | The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

- Jordan Wright