Spring Shows in Philadelphia

By • March 18, 2016 0 1953

It happened in Philadelphia: 56 men in breeches created a nation.

Then, 51 years later, it happened again. This time, it was 53 men in trousers. And what they created was … a flower show.

Actually, what they created in 1827 was the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society. The first public show, featuring the poinsettia’s American debut, came two years later. (In 1835, the society admitted women as voting members — long before the nation did.)

The descendent of that historic event, the Philadelphia Flower Show, the largest and longest-running indoor show in the world, now attracts more than 200,000 visitors over nine days. The 2016 show, at the Pennsylvania Convention Center, ends this Sunday.

A Garden of Eden for plant-lovers — with award-winning specimens, lectures and vendors from around the world — the show is also a floral theme park that seems to grow Disney-er every year. Since this year’s theme is “Explore America: 100 Years of the National Park Service,” expect recreations of Yosemite, simulated Old Faithful eruptions and a Denali sled dog team. You can even “create your own Mount Rushmore floral headpiece.”

For details, and to reserve a garden tea or an early-morning private tour (weekdays only), visit theflowershow.com. Families with children should note that on closing day, Sunday, March 13, there will be a Flower Show Jamboree and a Teddy Bear Tea.

Prior to launching their kisses-and-hugs “With Love, Philadelphia” campaign, Visit Philadelphia’s slogan was “Philly’s More Fun When You Sleep Over.” With the Flower Show meriting a full day and three new museum exhibitions, it makes sense to get a room.

After a controversial legal and financial intervention, the Barnes Foundation galleries relocated from the suburban residence of Albert C. Barnes (1872–1951) to a new museum on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in 2012. The move’s approval hinged in part on the exact reproduction of the unchanging salon-style display found in leafy Merion by the relatively few visitors who made it out there.

Architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien created a large and spacious modern building for the Barnes in which the tiny recreated rooms are encased. In accordance with Barnes’s eccentric theories of art appreciation, African, Native American, Pennsylvania German and other sculpture and artifacts, including miscellaneous wrought-iron objects, share the walls with frame-to-frame masterpieces by Renoir, Cezanne, Matisse and Modigliani (to name a few of Dr. Barnes’s favorites).

It is one of the most astounding museums in the world, now with the additional reason to visit of special exhibitions. Through May 9, the Barnes (which has 22 paintings by Pablo Picasso in its permanent collection) is hosting “Picasso: The Great War, Experimentation and Change.” The show’s focus is the period surrounding and including World War I, during which Picasso — the “High Priest of Cubism” in the words of curator Simonetta Fraquelli — abruptly returned to a naturalistic style, continuing to alternate between Cubism and Neoclassicism.

A video illustrates how during the war Cubism was portrayed as anti-French (though the style’s co-creator, Georges Braque, was as French as could be and served at the front) and associated with the despised Germans.

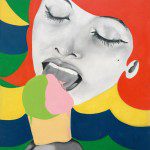

Several blocks up the parkway from the Barnes, “International Pop” is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through May 15. All the American stars are represented, of course: Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Tom Wesselman, Ed Ruscha. But what makes the show an eye-opener are the works by what the text calls the “British forbears of Pop,” notably Edinburgh-born Eduardo Paolozzi and London-born Richard Hamilton, whose collages date to the 1950s (earlier, in Paolozzi’s case), and by artists from throughout Europe and from Argentina, Brazil and Japan.

Finally, across the Schuylkill River, the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology is the exclusive U.S. venue for “The Golden Age of King Midas,” on view through Nov. 27. Of the 100-plus objects on loan from Turkish museums, many were excavated by Penn archaeologists from an eighth-century B.C. royal tomb, believed to be the resting place of Midas’s father Gordios.

Whether you hear the clatter of gold or of your muffler when you think of Midas, this exhibition is another example of the remarkable things to be seen this spring in the City of Brotherly Love.

- The Philadelphia Flower Show is the world’s largest and longest running indoor show.

- Jordan Wright