‘The Valkyrie’: Wagnerian Family Values of Love, Life and Death

By • May 20, 2016 0 1120

When you encounter Richard Wagner and each entry into his monumental Ring Cycle, it becomes not just going to the opera, but being part of an event. There’s a frisson and a challenge involved in just being there, and sometimes, as it happens, it becomes even more so.

That was the case with the Washington National Opera’s production of “The Valkyrie” (which followed the prelude “Rhinegold”) Monday, which began with a certain nervous anticipation at the news that British soprano Catherine Foster would not be able to perform the critical role of Brunnhilde due to an injury sustained during rehearsals. Plus, there was a powerful thunder storm that seemed to accompany the run of the five-hour night.

But with the American soprano Christine Goerke, who is something of the queen of Wagner in the United States, taking on the role and singing and performing the role as if she’d been rehearsing from the beginning, any concerns about uncertainty or a drop in quality were quickly dashed when she made her appearance.

Of all the operas in the cycle — “Siegfried” and “Twilight of the Gods” were yet to come — “The Valkyrie” (“Die Walkure”) contains some of the cherished and familiar music as well as the tropes and clichés that lie in the popular imagination about all things Wagner. We have memories of Brunnhildes and Siegfrieds, heroes and heroines, of swords and helmets and opera stars from the past. The musical themes are familiar as a kind of thunderous muzak that reels around in our heads, and in the Vietnam War epic “Apocalypse Now,” in which U.S. Army helicopters rode over beach waters during an attack, blasting out the Valkyrie theme.

To suggest an opera or any sort of musical work is Wagnerian is to think in terms of overwhelming excess, especially musically, but also as a work of theater. This production was not so much overwhelming as it was complete and clear and emotionally fulfilling. The music as presented and played, led by conductor Philippe Aguin, had a lot to do with that. Because this production seemed to highlight its narrative aspects, the music, while providing the necessary moments of being swept away, of surging and cresting, buttressed the storytelling and mined it for its emotional and intimate contents.

You have to accept a lot about art making unbelievable things as real as a postcard from a loved one or a bill from a tax collector. This is a world of gods, of dwarves, of giants, of fantastical creatures, of fire and storms, of earth and a heaven drawn up by an immortal architect where slain heroes are taken from the battlefields by a flying sisterhood of immortals, where a cursed ring made from Rhine gold has the power to rule, save and destroy the world, gods and mortals alike.

While director Francesca Zambello has chosen a setting that suggests both a primitive America (think of Albert Bierstadt’s epic paintings) and a rusting industrial landscape threatening nature, the production also remains rooted in myth on a grand scale. The many projections, of swirling, rising river waters, and dark and primeval forests set off against factory smoke and skylines, are suggestive and ominous, and also threatening. In fact, when audience members walked outside for the first intermission, they were confronted by the very same threatening clouds — and thunder and lightning — so that when those same images returned on stage, they seemed like live news feeds.

In “The Valkyrie,” events set in motion in the prelude begun to gurgle up when Sieglunde, leading a fraught domestic life in the forest with her husband Hunding, confronts an exhausted stranger seeking shelter. He is an outsider, and as it turns out, a man nurtured to be a hero by Wotan, the leader of the gods. His name is Siegmund, and he is Sieglunde’s twin brother, and they fall instantly, heroically, madly and all the ways you can fall in love.

From this comes a rightful conundrum for Wotan, who must confront his outraged wife Fricka, the goddess of marriage, who insists that the lovers must be punished, and the heroic Siegmund must die. For this to happen, Wotan demands that Brunnhilde, his much beloved daughter and leader of the Valkyrie, assists in the death of Siegmund at the hands of Hunding. But Brunnhilde, observing how Siegmund refuses a hero’s death and remains immovably attached in his love for his sister, disobeys Wotan’s will. The results of that are, to say the least, epically catastrophic for both.

They are all the potent, fiery ingredients of a long night that seems to envelop the audience at the speed of anxious hearbeats.

Once again, Wagner has sectioned off the work: the meeting and fulfillment of Siegmund and Sieglunde takes up nearly an hour, and, with the music ever more sweepingly romantic and classically Wagnerian, it is the discovery of each other by the siblings. It is one long, soaring duet, masterfully sung by the appealing and richly voiced American soprano Meagan Miller and the almost frantic but able British tenor Christopher Ventris. It reminded me of the equally long section of the WNO production of Wagner’s “Tristan and Isolde,” during which the impassioned lovers realize then fulfill their love for each other. “That man does love duets,” one observer noted.

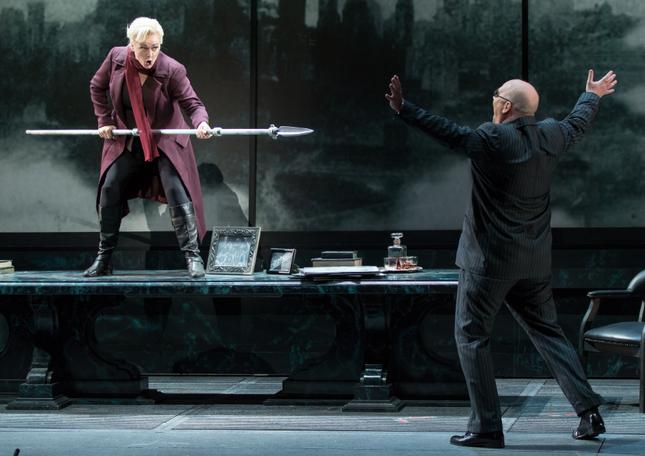

The trickiest — and it seemed to me most difficult — section takes places in Valhalla, which looks more like the board room in Trump Tower, where Wotan confronts his furious wife and then tasks his beloved daughter. Fricka, perhaps naturally, objects not only to the adultery but also to the incest. Wotan suggests to her that she’s afraid of anything new, which convinces neither Fricka nor, truth be told, the audience.

Once Goerke is on stage, she takes full command of it with every note, every strong step, every bit of feeling. She and Held — but also the young lovers — are the character standouts in this production.

Brunnhilde arrives, expressing her joy at being with her father in the most full-voiced and natural of ways. But Wotan then launches into what is basically the narrative of everything that’s happened so far and Held gives this exposition the kind of clarity it needs, and in this his singing — there isn’t much variety to be had in exposition — is aided and abetted by the music, which brings focus and musical embellishment to the tale being told and sung. There is real anguish and frustration in Held’s Wotan and, later, disastrous anger.

In the climax, the Valkyrie make their appearance by gliding and flying down in parachutes, much to the aural delight of the audience, which treat this somewhat like children at fireworks. The sisters — all of them Wotan’s daughters (but not by his wife) — tidy up and police their gear like well-trained soldiers, bringing with them the portraits of the fallen dead.

In the end, Wotan, furious at Brunnhilde for defying his orders, strips her of her immortality and condemns her to a sleep from which she can only be awakened by a worthy mortal.

This is the worst kind of punishment and a breach of trust and love, and the moments and the singing leading up to the end are heart-breaking — in a way that can only happen in Wagner. It’s the definition of loss and confusion, of terrible life itself, it’s spectacle — a ring of fire — but it’s also deeply intimate.

In the end, The Ring, as it is wont to do, has spoken, and not for the last time.