Here in the mid-Atlantic states the ubiquitous seashell symbolizes the arrival of summer. Wherever there was watery life there is a seashell, and shells have had cultural and artistic symbolism throughout history. They have been collected and traded in one form or another since at least 3,000 B.C. The civilizations of Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenica and Greece all incorporated shells into their cultures and used them to decorate their homes, their clothing and themselves, or to adorn the dead before burial.

Shells seem to have inspired half the architects of Europe — or at least their rich patrons. Bath House, an elegant estate in England built in 1748, was decorated with huge swags of seashells hung over the windows and mantle, as one might do with pine boughs at Christmas. And Frederick the Great built an elaborate shell grotto at Sans Souci, in Potsdam, in the 1760s.

Legend has it that during their long voyages in the 1800s, New England whalers made octagonal, hinged, mahogany boxes with glass tops and fashioned colorful West Indian shells into intricate shell mosaics under glass, as gifts for their lady loves. Known as Sailors’ Valentines, they are synonymous with the romantic whaling lore of Nantucket and 19th-century New England.

Although some lovesick sailors could have relieved the tedious hours at sea by crafting these valentines, historians and collectors disagree about such origins. They say it was natives, particularly those in Bridgetown, Barbados, a central port-of-call for many whaling ships, who made them. Sailors would buy or trade items for these nautical tokens as romantic gifts to take home to their lady loves upon reuniting after their long sea voyages.

In 19th-century West Indies, a souvenir culture thrived in response to sailors hoping to bring back mementos. While a few Barbadian women may have crafted them for extra income, some local shop owners established cottage industries, hiring locals to make valentines, which were sold to sailors. The label, “Dealer in Marine Specialties and Native Manufacturer in Fancy Work,” is occasionally found glued to the bottoms of early valentines that were sold at the Bridgetown shop of B.H. Belgrave. Many times these early examples incorporate the words “Gift from Barbados” or “Present from Barbados.” Some early valentines are backed with Barbadian newspapers, further substantiating Barbados as the place where many of these curiosities were manufactured.

It is thought that the original boxes may have been repurposed compass boxes from whaling ships, but the significant uniformity of design, including the octagonal shape of the box, suggests that they were produced in volume under someone’s direction. Valentine production reached its height in the mid- to-late 19th century, although some earlier examples are known.

Condition is important when considering the purchase of a sailors’ valentine. The work should retain most of its shells and the box should be as damage free as possible. The more desirable valentines incorporate anchors, vases of flowers, or exceptionally detailed single flowers. Valentines with sentimental sayings of love and friendship are the most desirable. Prices today range from $3,500 to $8,500, or more, for a box with a single design to $8,500 to $19,000 for one with a pair of shell designs.

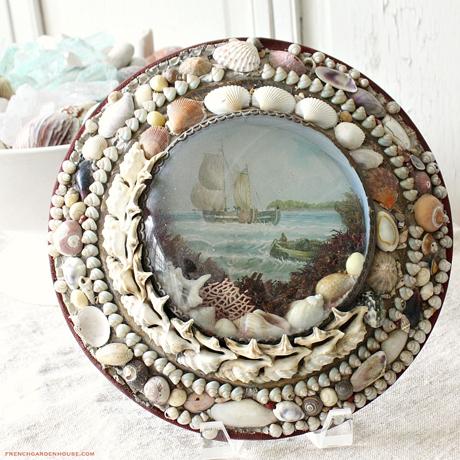

Ultimately, the shell-work souvenir “industry” expanded beyond sailor’ valentines. Among the most popular souvenirs were shell roundels, sometimes called “bull’s eyes,” which had colored prints of clipper ships and fishing boats under domed glass coverings. The shell-encrusted frames were usually circular or heart-shaped. These are extremely rare and avidly collected and can cost upwards of $3,800 for a well-crafted piece in good condition.

By the late 1800s, Victorian love for collecting and displaying exotic objects from faraway lands may have fueled the popularity of shell work. It was fashionable to embellish picture frames, boxes and vases, and create grottoes with colorful shells. As ships brought back entire cargoes of shells for the whims of the aristocracy, Victorian ladies could purchase shell work supplies in some of London’s toniest shops, where packets of sorted shells were sold, accompanied by printed patterns for forming shell flowers, boxes and frames. Every major city in Europe had such shops, and shell work became a pastime enjoyed by many. Of course, whatever the fashion was in Victorian England was soon all the rage in American cities. American-made shell art is found more often in coastal and resort towns in the northern states.

That any of these delicate artifacts survived is a testament to how they were treasured by their owners. Collectors keenly seek sailors’ valentines and Victorian-era roundels; even dealers are reticent to sell them.