An Open Wound, A Widening Chasm

By • July 11, 2016 0 1066

How quickly the world can come to be seen as being in a state of chaos.

How quickly events — two police shootings of black men separated by a great distance, followed by a black sniper’s assassination of five police officers in Dallas — can unravel the emotions of a whole country and expose its naked, raw divisions. Once again, race has become an open, literally bleeding wound.

You can look at Monday’s Washington Post headlines, the Google headlines, the nonstop CNN ticker tapes and begin to feel dizzy with conflicting feelings of anger, sadness and confusion. See what you can make of all this, from the Post’s Monday edition, all referring in one way or another to the last week’s violence and its aftermath: “Protests, frustration continue,” “More Than 200 Arrests In 5 Cities,” “Dallas chief says gunman appeared delusional,” “For rattled city, soul-searching in houses of worship,” “Activists see hints of Ferguson in (Baton Rouge) police force,” “As arrests mount Baton Rouge police tactics questioned,” “Respite of partisan finger-pointing after killings proves to be short-lived,” “Police react with anxiety about safety, sadness for losses,” “Officers across the US are more wary ‘like they were under siege,’” “Black Lives Matter activist arrested in Baton Rouge,” “Minnesota officer who killed black motorist was model student, professor says,” “Let’s praise God for these officers,’ Dallas pastor says.”

There are also pictures: Black Lives Matter marchers in Dallas hugging, a demonstrator in Baton Rouge, pulled to the ground, described as being “detained” by two baton-wielding helmeted officers. On the bottom of the page, a smaller picture of a black woman holding up a sign with bold red and blue letters: America Help Us.

Help us indeed.

If you watched television, late at night Thursday through now, if you went to Facebook and saw that wrenching video of the dying black man, if you still hear the shots in the night at Dallas and see the pictures of the murdered police officers, if you looked at the angry faces of the marchers and the running and screaming and objects flying through the air, then listened to the often bristling arguments of politicians, strategists, ministers, mayors or police chiefs, experts and media types, you could be forgiven if you clenched your fists, hung your head in sorrow, started pacing nervously, argued or not, yelled or not, threw up your hands or not.

It’s about who we are and what we think about who we are — and how that fits into what has happened. We are, all of us now, skin-color wise and in terms of how we are asked to feel, black or white, giving new and deeper meaning to the phrase “colors our thinking.” In an atmosphere like this, where black men have again been shot by police in separate events, where five white police officers have been killed by a single and efficient and clearly revenge-motivated black man, we become to some degree people of color. At the time, we feel the urge to want to know more than that, to empathize and grieve with the whole — not a little more, or a little less for one or the other, but both, together (so that we can become one and whole).

The most important thing, it seems to us, is that the events of the past week and ongoing reactions are strung along the same line of rope, that they are connected by tears and fears, and by blood, and should be considered together, as well as apart. As we watch and listen, read and react, most of us are like everyone else, survivors and citizens, trying to reach across a widening chasm to some sort of understanding. That’s what’s hard about this: that it is painful to watch, to read about and to somehow sort it all out.

But some things linger more than others. At some primal level, it’s impossible to ignore the videos of shootings, of dying, of mourning and outraged grief. But it’s fair, we think, to say that we should try to tune out voices that want us to blame and therefore hate somebody — blame and hate the police or the marchers or Democrats or Republicans. Let’s tune out those false arguments on television between senators and media types. Let’s tune out the blamers, let’s tune out the shrill.

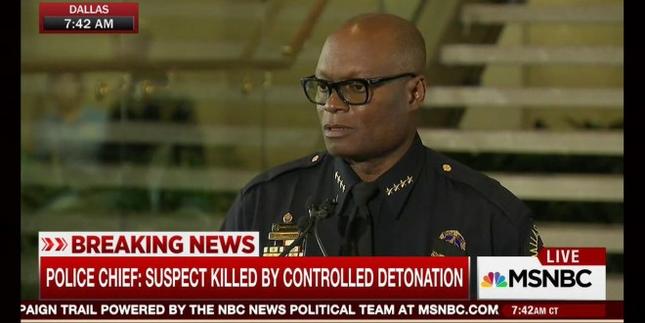

Let’s tune in the prayer service in Dallas, the acknowledged progress made by community and police force in Dallas. Let’s credit the impassioned voice of the city’s white mayor and the impassioned voice of its black police chief, whose life experience and story ought to give him more authority than anybody else in the field. Let’s tune in to the stories of those police officers who were lost and the stories of the two men who were shot by police: those stories are tied together irrevocably now. Let’s tune out the man who killed the five; he is and was, for whatever reason, an enthusiastic killer and murderer.

There are those who suggest that Black Lives Matter marchers are at fault, or that the slogan itself is at fault. But it’s some of the tactics that are at fault, not the cause or the phrase itself, when objects started being thrown in Minnesota and Baton Rouge. The Dallas BLM march, with the total cooperation and protection of the police was completely peaceful until the horrible shots rang out.

It seems to us that we are suffering a kind of shock and a failure of empathy and imagination on all sides. None of us who is not a police officer knows what it’s like to be one. If you are white, you cannot imagine what it is to be black in America and what that might mean in an encounter with police. The duty of all police forces, and this is something that seems to have occurred in Dallas, is to remember that they are the protectors of the community, not its masters.

The media, and that includes the newspapers, television groups and social media, share the responsibility to report fairly, accurately and with less fever the ordeal this country is experiencing. They also share the blame when they don’t.

The New York Post, for instance, which shrilled “Civil War” on its cover last week, seems to have regained its natural tabloid footing. Above a big headline which read, “Scarlet Letter, Dallas Police: Massacre Maniac Left message signed in blood,” we were brought back to celebrity reality with “Dressed to Thrill: Inside Derek Jeter’s Wedding.”

In times like these, that sounded almost normal. Or not.