A Contradictory Convergence of History, Fiction and Politics

By • September 12, 2016 0 1038

In art and politics and daily life, fact and fiction often comingle, sometimes providing refreshing succor, at other times sowing nagging confusion.

For over a year now, Americans have been dealing with a particularly anarchic and recklessly negative political campaign, a race for the presidency in which fact and fiction, truth and non-truth and outright lies dance around one other, uncoupled and sometimes conjoined.

The result has thrown the election process and campaign, not to mention prospective voters, into a kind of feverish dither. We seek relief from the calculations of candidates, pollsters and experts. We shudder at daily Trumpisms. We listen to music, go read the baseball stats, anticipate another year of Redskin Fever or go to the movies or the theater, where surely there must be less of this keen confusion.

This past week and weekend were a time when all these forces — remembrance of history, engines of fiction and politics — seemed to converge. These were, after all, the days leading up to the 15th anniversary of 9/11, that most thunderous tragedy that was visited upon us by terrorists on a bright-blue-sky Tuesday, nearby and in the proximity of unforgotten real-time television imagery.

That solemnity of remembrance in New York, at the Pentagon, in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, the salute to courage and the commemoration of great personal and human loss, gave off contradictory echoes.

On the one hand, the searing clarity and still wounding sadness of those events seemed a far and honest cry and contrast from this dangerously divisive election campaign, with its calls to distrust the other, with its remarkable vulgarities and exaggerations and fear-mongering.

On the other hand, the events of Sept. 11, 2001, make up some of the integral materials of the campaign of 2016, the “debates,” often strident, hysterical, tinged by fear and hatred, about national security, American “strength” and muddled strategies for defeating ISIS/ISIL, the current manifestation of Jihadist outrages, born in the acrid smoke and losses of 9/11.

Yet, there were at least two occasions for us to feel inspired, uplifted, optimistic and hopeful. They came from the arenas of theater and film, and they came in the form of a play and a movie dealing with real events in artistic and creative ways, managing to remind us that people will rise to the occasion in fits of courage, empathy, neighborliness and the impulse to help.

Both instances involved big airplanes, and big hearts and spirits. They came rooted in a story about what happens when a small town in Newfoundland is all of a sudden faced with the prospect of dealing with nearly forty major modern airplanes and their some 7,000 passengers. They came rooted in another story about a pilot forced in a choice made in a few seconds to belly-flop his plane in the frosty waters of the Hudson River.

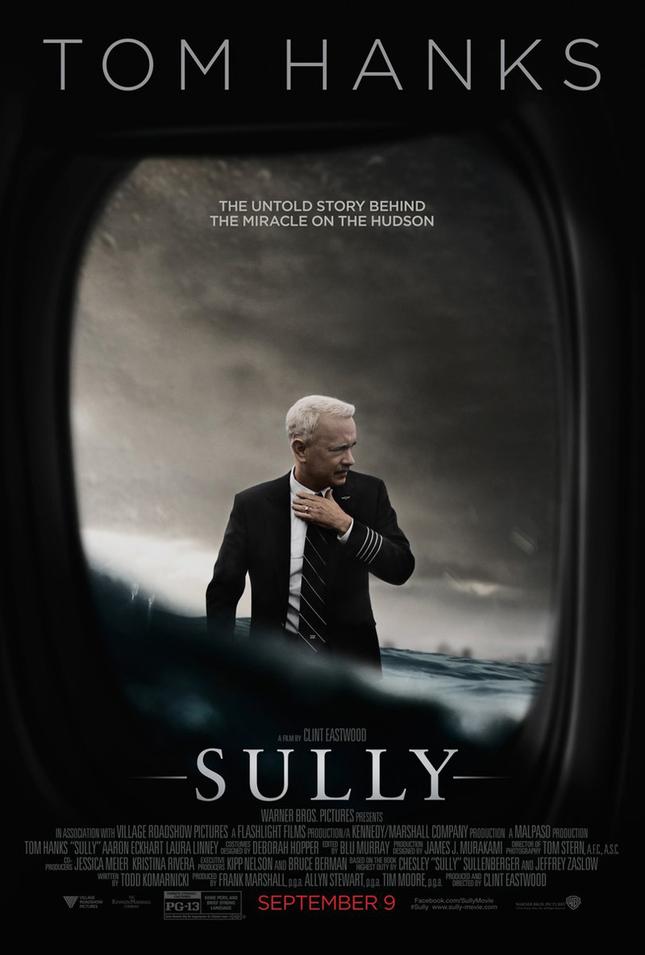

They came packed in a play — a musical no less — called “Come From Away,” now at Ford’s Theatre, which celebrates the ability of human beings to rise to the challenge of finding a way to accept and help a completely overwhelming arrival of what can only be called multinational refugees. They came in a movie directed by the craggy and venerable Clint Eastwood called “Sully,” which celebrated the craggy and venerable heroism of a pilot named Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who managed with his copilot to ditch his plane in the river, thus saving every one of the 150 passengers aboard.

The genre, the form and the styles of these two creative enterprises couldn’t be more different. “Come From Away” (which we highly recommend as a remedy for election fatigue) has book, lyrics and music by the duo of Irene Sankoff and David Hein, a concoction sweetened by optimism, humor and at least 14 musical numbers. The cast of 12, portraying both townspeople and sundry passengers from all over the world, play with unabashed seductive aggression to the audience — and the audience, I’m guessing, always gives in.

In short, “Come From Away” is almost totally theatrical and artificial. And yet, more than any convention speech or promise or even argument you might get into, it’s persuasive and feels authentic. Everything on any stage, of course, is an affectation, even those full of affection, even the Bard’s best. The logistics of what happened in Gander, Newfoundland, are, of course, impossible to recreate, but what with people bounding about the stage either in unison or emotionally floundering, you get a good idea of how impossible the task at hand was.

The stories and characters are sometimes straight out of Frank Capra — “It’s a Wonderful Life,” “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” and so on — but oddly enough the sentiment seems honest, the characters mirror-like. The confusion is that this is a kind of fiction about something that actually happened in the course of 9/11. One can only imagine how much of it is still acutely alive in the minds of all those people who came together that day. The gift — and it is an audience-pleasing gift — of all those involved in “Come From Away” is that you can indeed imagine that.

We happened to see “Sully” on the day of the 15th anniversary, when names were being called out into the air, when the president of the United States spoke in his eloquent fashion at the Pentagon and survivors gathered around the shrines of 9/11. We were part of an audience whose members were mostly older, ourselves included, who saw the events of that day on television with adult eyes and shocked hearts. “Sully” is not about 9/11, but it too, like “Come From Away,” has a contradictory feel to it, the echo of 2001 felt in a dark movie theater in 2016 from a 2016 movie about events that happened on Jan. 15, 2009.

The protagonist of “Sully” would appear to be the pilot of US Airways Flight 1549, but in truth there are numerous other characters — including the ambient skyline of New York City and its inhabitants — to consider and numerous characters of courage, intelligence and creativity. The forced landing, with its images of passengers standing on the wings of the plane, and the articulate, warm Sully, gave the city of New York a huge lift from its doldrums and memories. We see and feel not only the plane’s impact in the frozen Hudson, but the landing’s impact on the imagination and confidence of the city’s inhabitants.

“Sully” depicts the crash, and how it haunted both pilots, but also the interrogations, the coverage and investigation by the NTSB in its aftermath, a loaded-gun kind of construction that threatened Sully’s career and the sullying of his reputation.

The film — which fills out its narrative by going backward and forward in time with remarkable clarity — is as much about the crash itself, dramatic and intense, as it is about the hearing and its outcome. With Tom Hanks (who doesn’t trust Tom Hanks?) as Sully, we’re in good, moral hands. Yet the film at times seems also haunted by 9/11, as we still are, especially on the anniversary. Those images of a huge jet plane flying across the skyscape of Manhattan almost immediately invoke similar images from 9/11, not to mention Sully’s 9/11-ish nightmares.

Clint Eastwood, it should be noted, is 86. He directed this film with a clear-minded unsentimentality, without frills or stirring music. His focus is on the story, and on character. All of the people in it, from a bartender to a street cop and a ferry pilot, are sharply drawn. It seems we know something of them right away. It’s a remarkable achievement for a man who greeted us long ago as a spaghetti-western hero and continues to surprise us. It’s a safe bet that Eastwood won’t go down in history just for that moment of talking irreverently with a chair at the Romney Convention.

Which brings us back, of course, to reality. On 9/11 anniversary day, we found out that Hillary Clinton had pneumonia, diagnosed last Friday. And there was no relief from the issues of the day. All across the official start of the football season, the issue of whether players should stand or not for the national anthem engaged fans at least as much as the fact that Tom Brady wasn’t playing.